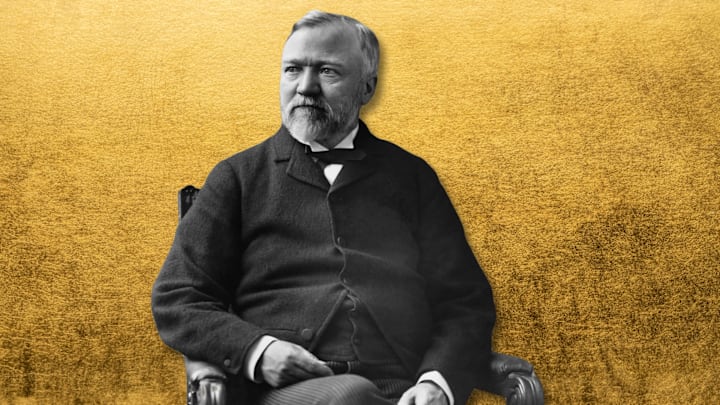

Long before Musk, Zuck, and Bezos, Andrew Carnegie (pronounced car-NE-gie) was one of the richest men in the world. But unlike his modern-day peers, Carnegie dedicated much of his life to getting rid of as much of his wealth as possible. Here’s what you need to know about the man whose philanthropy is still paying societal dividends today.

1. Andrew Carnegie was born in Dunfermline, Scotland.

“I was born in Dunfermline, in the attic of the small one-story house, corner of Moodie Street and Priory Lane, on the 25th of November, 1835, and, as the saying is, ‘of poor but honest parents, of good kith and kin,’” Carnegie (who was named after his grandfather) wrote in his autobiography, published in 1920. His parents William and Margaret worked as a weaver and sewer for shoemakers, respectively. According to the Carnegie Corporation, “[Dunfermline] fell on hard times when industrialism made home-based weaving obsolete, leaving workers such as Carnegie’s father, Will, hard pressed to support their families,” ultimately leading the Carnegies to immigrate to the U.S. in 1848.

2. Carnegie’s first job was “bobbin boy.”

After immigrating to the U.S., the Carnegies settled in what was then a town called Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, and 12-year-old Andrew got a job at a cotton factory in Pittsburgh to help support his struggling parents. He earned just $1.20 a week changing spools of thread.

3. His avid love of literature began at a young age—thanks to a philanthropist.

Colonel James Anderson was a local who let young apprentices and working boys borrow tomes from his personal library once a week. When management of the collection fell into other hands, the service remained free for apprentices only; a $2 annual subscription fee was added for working boys, including Carnegie, who at that point was a messenger. Outraged by the change, Carnegie wrote two letters to the local newspaper pleading his case—and won. Carnegie later said the access Anderson provided to books changed his life. “To him I owe a taste for literature which I would not exchange for all the millions that were ever amassed by man,” Carnegie wrote in his autobiography.

4. Carnegie worked his way up in the railroad industry.

When Carnegie was working as a messenger boy in a telegraph office, he was noticed by the superintendent at the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, who hired him to be his personal secretary. From there, Carnegie’s career skyrocketed—he later claimed the superintendent job for himself, then invested in the company that invented Pullman sleeping cars. The investment made him quite well off, but it was his further investments in the steel industry that made him one of the wealthiest people in history.

5. He had an unusually close relationship with his mother.

After Carnegie became wealthy, he and his mother Margaret lived together in a suite at New York’s Windsor Hotel. She often attended his business meetings. Margaret was so unhappy when her son, then 45, began courting Louise Whitfield, that they kept their eventual engagement a secret until after she died—more than three years later. The couple didn’t marry until April 1887.

6. Carnegie’s “workingman’s hero” status was shattered by the Homestead Massacre.

Carnegie’s public image aligned with his real-lie “rags to riches” tale—he supported working class and labor causes, even the right to unionize. But behind the scenes, his attitude was a quite different.

In 1892, violence broke out at Carnegie’s Homestead, Pennsylvania, steel mill when union workers protested wage cuts. Carnegie departed for vacation in Scotland, leaving his second-in-command, the heavy-handed Henry Clay Frick, in charge. Frick locked workers out of the mill and brought 300 Pinkerton guards in for protection. “We all approve of anything you do,” Carnegie wrote to Frick.

At least 10 men died when workers clashed with the guards; ultimately, union leaders were arrested and Frick brought in replacement workers. The union workers eventually came back to work, making 60 percent less than they had been previously. When Frick wired him that the strike was over—saying that “We had to teach our employees a lesson and we have taught them one they will never forget”—Carnegie responded, “Life is worth living again.”

As a result of the strike, his reputation suffered from every direction—not only did laborers see whose side Carnegie was really on, others criticized him for making Frick do his dirty work.

7. He made $480 million when he sold his company.

Banker J.P. Morgan bought Carnegie’s company, Carnegie Steel, in 1901 for $480 million and folded it into U.S. Steel. Carnegie was paid in gold bonds and built a vault especially for their protection.

In 2015, the Carnegie Corporation estimated that at his peak wealth, Carnegie was worth $309 billion (accounting for inflation). For comparison, in 2022, Elon Musk is worth about $219 billion, Jeff Bezos is worth roughly $171 billion, Bill Gates comes in at $129 billion, and Warren Buffet clocks in around $118 billion.

8. He didn’t know his real age for 73 years.

Based on records from his birthplace in Scotland, Carnegie had always believed that he was born in 1837. When he visited the town at the age of 71, he realized 1837 was simply the year the record was made in the book—but he was actually listed as a 2-year-old child at that time.

9. He believed “the man who dies rich dies disgraced.”

In 1889, Carnegie published The Gospel of Wealth, publicly extolling his beliefs that personal wealth should be distributed for community benefit once your family’s needs were taken care of. “The problem of our age is the proper administration of wealth, so that the ties of brotherhood may still bind together the rich and poor in harmonious relationship,” he wrote in the first line of the essay.

He put his money where his mouth was: Carnegie gave away more than $350 million during his lifetime, proving that he lived by one of the most famous lines from The Gospel of Wealth: “The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.”

10. We have Carnegie to thank for Sesame Street.

In 1911, Andrew Carnegie founded the Carnegie Corporation to manage his philanthropic efforts, endowing it with a $125 million trust. In the 1960s, the Carnegie Corporation used some of those funds to research how television might be used to help educate kids, especially underprivileged children. The research eventually led to the Corporation providing Joan Ganz Cooney with the funds to develop Sesame Street and the Children’s Television Workshop. According to Sherrie Westin, executive vice president of global impact and philanthropy at the Sesame Workshop, “Sesame Street literally would not be here were it not for the bold vision and audacious philanthropy of the Carnegie Corporation.”

11. The Saguaro cactus is named after Carnegie.

The iconic saguaro cactus, which is found only in the Sonoran Desert in Arizona and Mexico, can live as long as 200 years and grow to be 45 feet tall. Its scientific name, Carnegiea gigantea, is a nod to Carnegie’s philanthropic contribution to botany: The Carnegie Institution, founded in 1902, helped establish the Desert Botanical Laboratory in Tucson in 1903.

12. Carnegie was a big church organ enthusiast.

He loved them so much that one of his major philanthropic efforts included donating 7600 of the instruments to churches across the United States. He also oversaw the installation of the 8600-pipe organ at Carnegie Music Hall in Pittsburgh in 1895 and had pipe organs in his homes in New York and Scotland.

13. Carnegie libraries are still scattered across the United States.

One of the philanthropic efforts Carnegie oversaw while he was still alive was providing over $40 million in grants for the construction of public libraries—nearly 1700 of them across the United States (he funded libraries in Canada and Great Britain, too). As of 2014, about 800 of those libraries were still functioning.

14. He didn’t leave much to his heirs.

In keeping with his wealth philosophy, Carnegie left his wife Louise a small amount of money, as well as their properties in Manhattan and Scotland, when he died. His only child, a daughter named (what else) Margaret, received nothing but a small trust. She eventually had to sell the family townhome because it was too expensive to maintain. But that was it—the rest of his immense wealth went to his charitable causes and endowments.

You might think that that would cause some resentment on the part of his heirs, but they apparently all agreed to the arrangement well before Carnegie passed away.

15. Carnegie wrote his own epitaph.

He wanted it to read, “A Man Who Knew How to Enlist in His Services Better Men Than Himself.” His wishes were not upheld, however—his gravesite includes a relatively simple Celtic cross bearing his name, birthplace, and lifespan.