Imagine an alternative universe in which there’s not one president of the United States—but three. Picture Theodore Roosevelt, Willam Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson all serving as co-presidents after the election of 1912, their Oval Office desks abutting like Gen Z coders at WeWork.

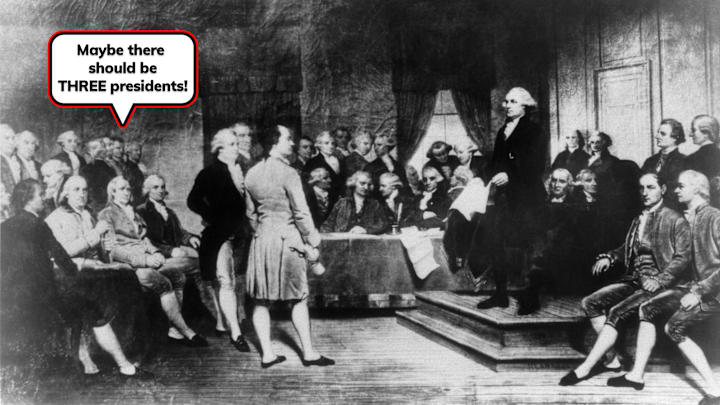

Yes, it sounds like the premise for a sitcom. But if a handful of Founders at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 had voted differently, it might have been reality.

We tend to think that the U.S. government’s structure was etched in stone from the very start. Of course we have one president and two senators per state. How could it be otherwise?

I spent a year immersed in all things constitutional for my new book The Year of Living Constitutionally, and one of the most striking revelations was the wide variety of ideas considered at the Constitutional Convention and the First Congress. All sorts of bizarre and fascinating notions were tossed around—including the five could-have-been versions of democracy below.

- Three Presidents

- Politicians Who Do What They’re Told

- A United States Without States

- A Handcuffed President

- A Ginormous Congress

Three Presidents

At the convention, Pennsylvania delegate James Wilson made a shocking proposal: That America’s government have a single person at its head—a president.

Immediately, several constitutional delegates objected, including Virginia delegate Edmund Randolph, who called the idea the “fetus of monarchy.” It seemed like a foolish idea for a brand new country that had just freed itself of a king after a long and brutal war.

Instead, Randolph’s idea was to elect a council of three presidents, each from a different part of the country. As wild as this sounds to our modern ears, it was nothing compared to what Benjamin Franklin had once suggested: That “instead of a president, the Congress appoint a 12-person ‘executive council’ whose members would serve for staggered three-year terms,” writes Walter Isaacson in Smithsonian magazine.

The debate was fierce, but Wilson was able to successfully make the case that more than one presidents would result in infighting. The states voted seven to three for a single president. In a sense, Randolph’s fears of a budding monarchy have been realized. Modern American presidents—both Democratic and Republican—have far more power over war, trade, and the nation’s direction than the founders envisioned.

Politicians Who Do What They’re Told

One rejected version of the First Amendment gave American citizens a huge amount of power over politicians. In this version, the First Amendment included the right of voters to “instruct Congress.” What was “instructing”? It had nothing to do with teaching. In this context, instructing meant that the people told their representatives exactly how to vote. It was practiced in some colonial legislatures [PDF]. The constituents would have a town meeting and say, “We the constituents of the Fifth District of Massachusetts, instruct our representative to vote yes on this bill and to vote no on this bill.”

Can you imagine how different the United States would be if the word instruct had remained in the Constitution? What if politicians really were just the messengers of the people’s will? Think of Texas Senator Ted Cruz saying, “Well, I don’t agree with solar energy, but I’ve been instructed by my constituents to pass this bill, so I suppose I vote yea.” We would basically have a direct democracy. Perhaps unworkable, but interesting for sure.

James Madison and other Founders, who feared mob rule, nixed the word instruct from the final draft.

A United States Without States

Several delegates to the convention believed that states were more of a pesky hindrance to the federal government than a helpful balance. At one point, Alexander Hamilton gave a speech advocating that the states all but be abolished, saying that it would be much more efficient and sensible to have a single unified government. He later claimed that he was misunderstood, and that he was OK with the existence of states, as long as they were weaker than the federal government.

Hamilton also proposed that the states be mere puppets of the federal government [PDF]. The federal government would appoint governors for each state, and those governors would have veto power over state laws.

One delegate—Pennsylvania’s James Wilson (again!)—proposed that senators be elected not by states, but instead by equal-sized districts spanning several states [PDF], which he believed would solve the battle between small and big states. If this had gotten through, maybe we’d be called “the United Districts of America.”

A Handcuffed President

As I mentioned, some delegates feared the president would become a king. The three-presidents idea was shot down, but there were several other ideas on how to stop the president from morphing into a tyrant. One proposal was to turbo-charge the power of the president’s cabinet, requiring the president to get its approval before acting. If this had come to pass, Joe Biden would have needed Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s thumbs-up before signing a law.

Another proposal was for the Congress to elect the president. The House and Senate—not American citizens or the electoral college—would choose who occupied the Oval Office. This system be similar to the parliamentary democracies seen in European countries such as Germany and Sweden. Its proponents believed it would discourage a president from attempting a power grab because he’d know that Congress could vote him out.

In the end, neither idea made it through, and the convention greenlit a presidential office with few guardrails.

A Ginormous Congress

In 1789, the First Congress passed 12 amendments to the Constitution and submitted them to the states for ratification. The states approved 10 of those 12 amendments, and those 10 became the famous Bill of Rights (the right to free speech, the right to bear arms, etc.).

So what happened to the other two original amendments? One lay in a zombie state for more than 200 years before being ratified in 1992 (it’s the Twenty-Seventh Amendment, which says that a sitting Congress cannot give itself a pay raise).

The other didn’t get approved by enough states—but if it had been, we would currently have a lot of congresspeople. The amendment stipulated that each Congressional district have a maximum of 50,000 American citizens, which means that, based on the current population of the United States, we’d have around 6600 congresspeople instead of our current 435. That’s enough representatives to fill Radio City Music Hall and then some. Nowadays, the average district has about 765,000 people, with the largest (Delaware at-large) with 989,948, according to the 2020 census.

Interestingly, this mega-Congress amendment wasn’t an afterthought. In fact, when James Madison created the list of those first 12 amendments, the 50,000-person limit was the very first amendment. The right to free speech was third (after the ones about congressional size and pay). So if all had gone according to Madison’s plan, journalists would be fighting for their Third Amendment rights, and the NRA would be focused on the Fourth Amendment.

Read More Articles About American History: