“I said get the f**k down here, you a**hole!”

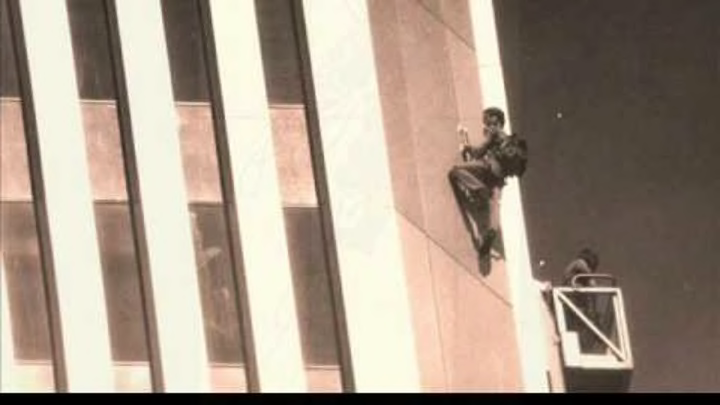

George Willig looked at the police officer bellowing beneath him. The cop had good reason to be upset: It was May 26, 1977, and 27-year-old Willig was hanging off a window-washing track on the south tower of New York City’s World Trade Center. Custom-made plates were snapped into the grooves of the track, which Willig used to hold his weight. As he moved up, the plates would slide and then lock into place, giving him the ability to move up the tower. Willig had made the devices himself, and they were all that stood between him and a gruesome end on the pavement below.

It was 110 stories to the top. No one had given Willig permission to treat the tower like a man-made mountain—certainly not the cop, who had no idea about the plates or tracks. All he saw was a madman who would almost certainly plummet to his death.

The officer kept shouting. Willig kept climbing. For the first 100 feet, he knew he’d be vulnerable to the interference of a fire truck’s extension ladder. Pretty soon he was high enough to be out of reach and out of earshot. Soon, more cops would arrive. So would bystanders and television cameras. All of them would have their attention trained on Willig, who was determined to ascend a quarter-mile into the sky and leave officials to wonder whether he was a hero or a criminal.

Assuming, of course, he made it to the top alive.

A Map to the Stars

When George Willig was a boy, his parents took him to the top of the Empire State Building. Looking out at the vast expanse of the city unsettled him.

“My father sat me on the ledge, where I could see over the edge,” Willig recalled in his 1979 book, Going It Alone. “A large plate of glass protected me from falling, and beyond this there was a railing with sharp metal jaws. All the same, looking down terrified me, and I clung closely to my father.”

That was in 1955, when Queens resident Willig was only 6. As he got older, any apprehension over heights seemed to leave him. He started climbing trees, then waterfall cliffs. His urge to move vertically earned him nicknames: the “Human Fly” and the “Mountain Goat.” In college, he scampered up to his girlfriend’s dorm building to her third-floor room and jockeyed his way up and over scaffolding used to close off rock concerts. As an adult, he segued to ice climbing. Navigating obstacles seemed to come easily to Willig. They were puzzles to be figured out. Or, as Willig noted in his book, “citadels to be invaded.”

After earning an environmental science degree, he worked a series of jobs before settling in at Ideal Toys as an inventor. It was there, while working on some uninspired toy projects, that Willig’s mind began to wander. He started to seriously consider an idea he had been batting around for months.

Scaling the World Trade Center, which had opened its doors in 1973, had been mentioned in passing in some of his climbing books and magazines. It was a frivolous idea, the kind of thing climbers might discuss in theory before moving on to more reasonable climbs. But to scale what was, for a brief period, the tallest building in the world (it would soon be surpassed by the Sears Tower) seemed irresistible. Philippe Petit had already used the towers in his own audacious spectacle in 1974, walking across them on a wire. The building was a canvas for a certain kind of high-risk artistry.

He wondered how best to go about it. Suction cups, like cat burglars in the movies? It was too far-fetched—Willig needed stability. When he went to visit the World Trade Center, he noticed each corner had half-inch C-shaped channels made of stainless steel. Each piece was 10 to 12 feet in height and secured by screws. The channels created tracks spaced 40 inches apart, which helped guide the window-washing apparatus necessary to clean the exterior of the building. But they were just to keep the platform positioned properly. They weren’t intended to be load-bearing—and certainly weren’t engineered to assist in a rogue climber making his way up the tower. But that was part of the challenge: Finding opportunity in a building inhospitable to his goals.

Willig eventually went up to the observation deck with a set of binoculars. He wanted to make certain the tracks went all the way up to the top. They did, which meant he had a path—however unconventional—that spanned all 110 stories, or 1350 feet.

Back on solid ground, Willig went to one of his former employers, Ark Research, and asked to use their machining equipment. Ark made aircraft-quality aluminum and steel parts, meaning anything fabricated there would be virtually indestructible—or at least strong enough to hold his 160-pound frame. Willig crafted a plate that snapped perfectly into the building’s C-shaped tracks. He could thread nylon stirrups through each plate, giving him purchase for the climb to the top. With a seat and waist harness, he could take his hands and feet completely off to rest if he wanted.

Crafting the plate meant repeated visits to the World Trade Center to test them out, which made Willig somewhat of a suspicious character. Once, a cop interrupted him while he was fitting the plate into the tracks. Thinking quickly, Willig said he was testing a safety device for the window washers.

It was at least partly true. The plate was a safety device. It would be the only thing keeping him alive.

Sky-Bound

Willig put off setting a firm date for his climb. He knew it needed to be springtime in order to avoid inclement weather and that he had to watch out for strong winds. It would be far easier to do it at night, when the chances of being seen were reduced. But doing so would cost him a grand view of New York’s skyline. It would also lessen his notoriety. There was something about being known for the climb and being seen that appealed to Willig.

Finally, he settled on May 26, 1977—one day after Star Wars opened in a handful of theaters around the country. He told his family during a barbeque what he planned on doing. They seemed surprisingly at peace with it. Willig had been climbing and clambering most of his life; if he said he knew what he was doing, they believed him.

Willig had co-conspirators, too, including his girlfriend, Randy Zeidberg, and his brother, Stephen, as well as his friend Jery Hewitt. Jery and Stephen intended to briefly escort him to the site and then leave. There would likely be criminal implications, and the fewer people involved, the better.

Willig woke up early that morning, ate breakfast, and got dressed in jeans, premium climbing boots, a striped t-shirt, a bandana, and a knapsack with water. He pulled a parka over his windbreaker in an effort to hide his climbing gear, which included the various plates, caribiners, and rope. At the bottom of the south tower, he squeezed through a fence that blocked off a small construction area. The plates went into the channels; Willig shucked off the parka and began climbing. It was 6:30 a.m.

For the first few feet, observers may have assumed Willig was a construction worker who needed to tend to something slightly above the ground. But the higher he climbed, the more obvious his stunt became. Cops from the New York Police Department and the Port Authority—which owns the World Trade Center—started beseeching him to come back down.

“Nope,” Willig said. “I can’t. These devices only work one way.”

As he ignored them, their demands became less polite and more profane. Willig kept moving up.

Below him, a police response was mounting. A 20- to 25-foot air bag was inflated, though Willig wasn’t sure what good that would do. If he fell, it wouldn’t likely be straight down due to wind. He also fretted about police coming to him from above on the window-washing platform on another corner of the tower. Willig thought he could rappel away from them using climbing rope.

“My concentration was so focused on the progress of my ascent that I was in something close to a meditative state,” Willig wrote.

As he continued up, he noticed floor numbers etched in pencil into the tracks—35, 40, 45—probably used as references during construction. “It was like coming across a bottle with a message on a deserted beach,” Willig wrote. Sometimes he peered into office windows to see if anyone would be able to look back.

An office worker wasn’t the first person he saw. It was a cop—actually, two cops. As Willig had predicted, they were being lowered from the roof on the washer scaffolding and met up with Willig near the 55th floor. The men—NYPD officer Dewitt Allen and Port Authority officer Glenn Kildare—took a different tact than the ornery cops on the ground. They gently asked if he was upset or “crazy.” Willig smiled. In fact, the plates and channels were working perfectly, and he had rarely felt safer on a climb. But to an observer, the stunt seemed outrageous. He tried explaining to Allen and Kildare how much he had prepared, but the vagaries of climbing strategy were largely lost on them.

“I judged by his responses to my questions, by the type of equipment he was using, and I guess you could say by the look in his eyes,” Allen later said of assessing Willig’s mental state. “Every response he gave me was reasonable. The only thing unreasonable about it was the fact that he was on the outside of the building.”

It didn’t really matter, anyway. Whether they thought Willig was disturbed or not, they had no choice but to ride the scaffolding in tandem with him as he made his way up. Trying to rein him in would only endanger his life further. So up they went, making small talk along the way. Allen said he was seriously considering taking up climbing himself. At one point, Willig extended a hand to sign autographs.

“Best wishes to my co-ascender,” he wrote.

Below him, a crowd had grown from hundreds into the thousands. More than morbid curiosity, they knew Willig was no amateur. He scaled with purpose and without any hesitancy. They cheered, though he couldn’t hear them.

He could, however, hear the news helicopters, which buzzed him for footage and still shots. This was possibly the only thing that truly rattled Willig’s nerves—the choppers moved in close. Eventually, a police copter chased them away.

By the time Willig was near the roof, his feet were blistered and his hands sore from trying to hammer the plates into the increasingly bent tracks, which weren’t totally uniform. Finally, he was within reach of a trap door on the roof. On the other side were police officers ready to hand him a rope he could use to pull himself up. Willig tried brushing them off—he could maneuver through the opening himself—but they insisted. Finally, at 10:05 a.m., after over three hours of climbing, Willig had made it. The only thing left was to find out what the consequences of his actions would be.

A Tall Order

The criminal charges came swiftly. Scaling the World Trade Center resulted in Willig being accused of reckless endangerment, criminal trespass, disorderly conduct, and the unauthorized climbing of a building. Three of Willig’s friends and family were charged, too, accused of aiding and abetting him. The city’s Corporation Counsel filed a lawsuit for $250,000, which it claimed was the cost of creating a rescue response to the incident.

A few days later, Willig appeared at a press conference with then-mayor Abraham Beame. The lawsuit, Beame said, was filed without his approval and would be dropped. So, too, were the criminal charges a few weeks later, though Willig had to agree to consult with the city on steps it could take to prevent future copycats. Daredevils materialized elsewhere, however. In 1981, Daniel Goodwin climbed the Sears Tower using Willig’s abandoned idea of suction cups as well as clips and rope.

Willig was, for a time, a sensation. Beame called his stunt “courageous.” News media descended on him and quizzed his parents. A lawyer hoped to patent his climbing apparatus, which was unlikely, as it had only one forbidden application: to climb the World Trade Center.

Time and again, he was asked why he did it. Earlier, cops questioned his brother, asking if there was any political message to it. Again and again, Willig said he has no angle and no agenda. “If I could choose any meaning for people to draw from the climb ... it would be that we all have within us the means to do, to accomplish, to become far more than we think,” he wrote. “Climbing was the key for me; for others it will be different pursuits. But the important thing is that people acknowledge what they want to do, and then have the courage to go after it.”

He received several offers for more urban climbing, including invitations to scale the Sears Tower in Chicago and the John Hancock Center in Boston. One promoter explained that he could arrange a “grudge climb” with Sir Edmund Hillary (he and Tenzing Norgay were the first two first mountaineers to reach the summit of Mount Everest). Most offers Willig rejected outright, though he did perform two climbs for broadcast on ABC’s Wide World of Sports, including a 1978 ascent of Angels Landing in Utah in which Willig plummeted 30 feet before a safety rope halted his fall. Mostly, though, he fielded speaking engagements.

In 1979, Willig left New York City to pursue stunt work in California. From there he moved to Sante Fe, New Mexico, where other, more conventional climbing opportunities awaited him. He largely remained out of the spotlight until 2001, when a coordinated terrorist attack sent two commercial aircraft into the World Trade Center and destroyed both towers. He worried his climb had drawn attention to the building, making it a more visible target.

But his intentions had always been clear. Willig wanted to inject some performative excitement into the city, welding his love of climbing with the kind of public spectacle practiced by Evel Knievel and tightrope walker Philippe Petit. Like Petit, Willig was chastised but not punished. The city’s fine for Willig ultimately amounted to $1.10, or one cent for every floor he climbed.

Additional Sources: Going It Alone