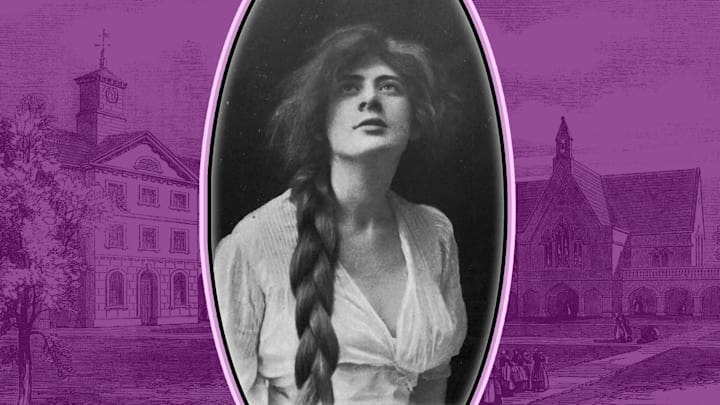

The harsh toll of the prison bell broke through the pattering of the cold morning drizzle. A small procession, comprised of a prisoner and her jail guards, passed through a gaping crowd of 4000 people who had braved the inclement Dorset weather to watch a spectacle of mortal agony. As the guards and the murderer reached the scaffold at the gates of the jail, only the prisoner, firm and unfaltering, ascended the wooden steps. “Resigned, penitent, and extremely calm,” in the words of one newspaper, Elizabeth Martha Brown turned to face the crowd before whom she would be hanged that day, the 9th of August, 1856.

“What a fine figure she showed against the sky as she hung in the misty rain, and how the tight black silk gown set off her shape as she wheeled half-round and back,” Thomas Hardy wrote, almost 70 years to the day after the execution. He had been one of the onlookers in the rain, a 16-year-old architectural apprentice, decades away from becoming one of the greatest novelists of the Victorian era.

“It had begun to rain, and then I saw—they had put a cloth over the face—how as the cloth got wet, her features came through it,” he continued. This event, which Hardy later described as “extraordinary,” had a profound effect on his psyche and left him with an overwhelming obsession with Elizabeth Martha Brown and the tragic circumstances surrounding her case. It is largely through Hardy and his heroine, Tess Durbeyfield, that the story of the last woman to be hanged in Dorset lives on.

A Pure Woman

Elizabeth Martha Brown had a far from promising start in life. As one of 11 children born to farm laborer John Clarke and his wife Martha, Elizabeth spent much of her childhood traveling between villages in the lush Dorset countryside, accompanying her father as he went in search of work. With so many mouths to feed on a menial worker’s salary, food was always scarce.

When she was 20, Elizabeth’s situation changed after she caught the eye of a local butcher named Barnard Bearn, a widower almost twice her age who already had two children. They married at St. Mary’s Church in the village of Powerstock in 1831. Barnard’s neat, flowing signature—the mark of an educated man with a successful business and a large estate—is visible on the marriage register. Elizabeth’s signature was a cross, an indication of her illiteracy. However, Bearn seems to have taught her to read and write in addition to offering prosperity and security. By the time Elizabeth witnessed the marriage of her sister Anne in 1840, she signed her name in full.

The couple had two sons, Thomas and William, but the family’s fortunes took a disastrous turn. First, the boys died during an outbreak of disease; then, in February 1841, Barnard died of pneumonia leaving Elizabeth £50 (worth nearly £5000 today).

Elizabeth worked for the next 10 years as a cook and housekeeper at Blackmarston Farm in Dorset. It was there that she met John Brown, a 20-year-old shepherd whom The Western Gazette later described as “a fine looking young fellow, standing near 6 feet high” with “very long thick hair.” Elizabeth, now 41, may have seen an opportunity with the younger man to regain the security she once enjoyed. However, it soon became evident that what John Brown saw in her was what remained of her £50 fortune.

After their wedding in 1852, the couple opened a small general store below their home, and John used her inheritance to set himself up in business as a carter—work that frequently took him away from home. John often returned drunk and abused her late into the night.

“I Was Almost Out of My Senses”

A few years into their marriage, Elizabeth suspected John of having an affair with Mary Davis, a much younger woman who ran a shop nearby. According to Nicola Thorne’s book In Search of Martha Brown, one local witness later recalled that Mary was a “lustful woman” who followed John into the stable whenever he was putting his horses away at night. If true, this may give context to the events of July 6, 1856. As her husband arrived home around 2 a.m., drunk and demanding the supper that she had made for him hours earlier, Elizabeth confronted him about the rumors of his affair. His reaction was instantaneous—and brutal.

“He struck me a severe blow on the side of the head which confused me so much that I was obliged to sit down,” Elizabeth recalled in her confession to the prison chaplain. Her husband then “reached down from the mantelpiece a heavy hand-whip, with a plaited head, and struck me across the shoulders with it three times.” Saying that he hoped to find her dead in the morning, Brown kicked her in her side, and then stooped down to unbuckle his boots—at which point Elizabeth seized the axe used to break up coal for the fire. “[I] struck him several violent blows on the head—I could not say how many—and he fell at the first blow on his side, with his face to the fireplace, and he never spoke or moved afterwards. As soon as I had done [it] I would have given the world not to have done it. … I was almost out of my senses, and hardly knew what I was doing!”

When she called her brother-in-law for help, Elizabeth insisted that her husband had been kicked in the head by his horse. But according to witness testimony given at the inquest the following day, there was no sign of blood in the horse’s stable—and there was some splattered on the walls of the house. Elizabeth was arrested on July 8 and taken to the Dorchester jail.

Just two weeks later, her trial commenced and lasted all of one day. Elizabeth stuck to her story despite intense interrogation by prosecutors, but it was of no use; she was found guilty of willful murder, and the jury gave her a sentence of death. Two days before her execution, she finally relented and confessed to the prison chaplain her role in her husband’s murder. But by then, it was too late to appeal her conviction or sentence.

Hardy’s Homage

To Thomas Hardy, watching as Elizabeth Martha Brown’s body hung limply from the noose, she was the true victim of the murder. The tragedy of her circumstances left an indelible mark on him. In 1926, Hardy asked a family friend, Lady Hester Pinney, to find out more about her life from the locals, explaining that he had a personal connection with the case and providing graphic details by letter.

Hardy’s wife, Florence, wrote to Lady Pinney, “Of course, the account TH gives of the hanging is vivid and terrible. What a pity that a boy of 16 should have been permitted to see such a sight. It may have given a tinge of bitterness and gloom to his life’s work.”

In Hardy’s 1891 novel, cleverly titled Tess of the D’Urbervilles: A Pure Woman, Faithfully Presented, the title character is a young woman seeking acceptance in a society that is eager to condemn her. Tess’s life heavily mirrors that of Elizabeth Martha Brown, from the protagonist working as a domestic servant to committing murder. Hardy uses Tess’s unfortunate circumstances to highlight the hypocrisy of Victorian ideals concerning women, particularly purity and sexual morality. Tess’s final act of standing up for herself is by killing the man who shamelessly abuses and betrays her.

Hardy does not describe Tess’s death in the same vivid detail as he remembered Elizabeth Brown’s. Instead, he writes that two onlookers watch the cornice of a tower as a tall pole is fixed to it. “A few minutes after the hour had struck something moved slowly up the staff, and extended itself upon the breeze. It was a black flag. ‘Justice’ was done …”

To the novelist, what was called justice for Elizabeth Martha Brown’s crime was anything but. Elizabeth, whom he called “the poor woman” in his letters, had crystallized the moral injustice women faced in an unequal society—and, as Tess, became a literary legend.