Not everyone attending the wake upstairs at The Admiral Lord Nelson Pub in Kilburn, near London, England, knew Michael “Mick” Meaney personally. But the Irishman had certainly developed a reputation. Meaney was known for great feats of strength in his labor-intensive jobs, for his love of boxing, and for his desire to become a professional fighter.

That was all in the past. In February 1968, Meaney lay in a coffin at the pub, with streams of people coming by to pay their respects. Eventually, pallbearers took the casket and passed it through an open window downstairs, after which the coffin was transported to a nearby yard, where workers began lowering it into the ground.

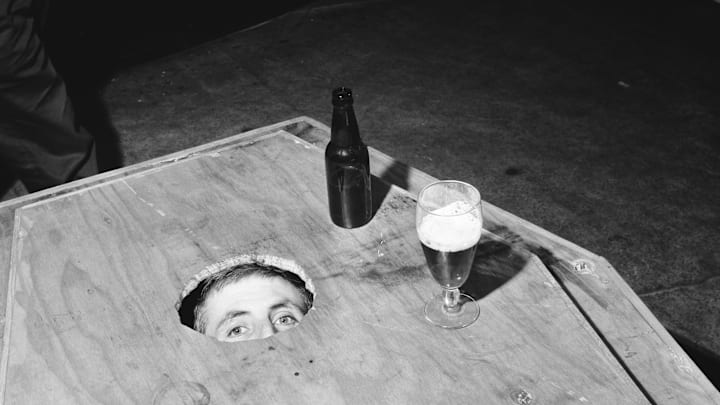

Through a hole in the box, Meaney gave the gathered crowd a wave. He was by no means dead. Instead, Meaney intended to be buried alive, his name achieving recognition far beyond the borders of Kilburn and across the world.

Providing, of course, he didn’t die in the process.

Dirty Work

Long before magician David Blaine suspended himself in clear boxes or in blocks of ice, 20th century culture had a small corner reserved for feats of human endurance. There were the phone booth contests of the 1950s, with organizers seeing how many people could be stuffed into one; flagpole sitting contests tasked people with perching atop a swaying, towering pole. People Hula Hooped until their hips gave out. During the Great Depression, they danced until exhaustion took over. The spectacles, many of them punishing, would usually attract a morbidly curious audience.

In the 1960s, the fad was human burial. Characters with names like Digger O’Dell welcomed mounds of dirt to be heaped atop them while they idled underground, with air and food passed to them via tubing. Texan Bill White had made a career out of it, dubbing himself “The Living Corpse” and amiably agreeing to be lowered into the ground to promote car dealerships, drive-ins, and other businesses. (He married Lottie Howard, another burial pro, by lowering a ring down into her casket.)

The records were usually self-reported and, as these things go, murky. Had anyone bothered to check up on a newspaper archive, they would have found predecessors. In 1933, an Illinois man named Jack Loreen claimed to have spent 64 days in the dirt. In 1963, Frank Allen, a circus clown in West Virginia, emerged after 73 days.

A lack of formal record-keeping, debate over coffin size, and, in some cases, poor publicity kept these men and others from having perpetual bragging rights. What was important was that Meaney believed he could go longer than anyone had ever gone before: In this case, longer than White, who at the time boasted of a record 55 days, Loreen and Allen be damned.

“They are all invisible people to me because I have never seen any of them go down in my life,” he said of previous attempts.

Meaney, a 33-year-old laborer, was fit and stout. More importantly, he had a burning desire to be recognized for something. Dreams of boxing were waylaid by a hand injury. The burial fad seemed like a good fit—all it would require is a strong mind and will.

That, and someone to handle the logistics. For that, he turned to Michael “Butty” Sugrue, a onetime circus strongman who was locally famous for feats of strength and who owned The Admiral Lord Nelson Pub. Sugrue knew how to draw attention, like the “live wake” that preceded the burial. The two managed to strike a deal with Mick Keane, who owned the truck that would transport Meaney as well as the land that would host his coffin. (Not among Meaney’s co-conspirators: his wife, Alice, who found out what her husband was doing only after hearing about it on the radio and while expecting the couple’s second child.)

“I think I’m appointed by my maker to become the underground champion of the world,” he said later. “I wanted to win the world title for my wife and family, most because I always wanted my daughter in the years to come—she’s aged only 3 now—to always say her father was a world champion.”

On February 21, 1968, Meaney had one last meal above ground before committing himself fully to the stunt. As Irish tenor Jack Doyle sang, scores of spectators—some missing work—watched as he was lowered between 8 and 11 feet (accounts vary) into the ground, heaps of dirt covering everything but the two exposed pipes for air and food. If Meaney was claustrophobic and never knew it, he was about to find out.

Incredibly, Meaney’s was not the only voluntary burial taking place. In Texas, habitual burial enthusiast Bill White was also getting soil shoveled over him yet again, intent on maintaining his own record. What Meaney had meant as a competition against himself would turn out to be an endurance test between two men. Who would break first?

Lowering Himself

Meaney’s coffin measured 6 feet, 3 inches long, 2 feet, 6 inches wide, and 2 feet high. It was also lined with foam, presumably for whatever comfort that might provide, and a hole in which Meaney could relieve himself. Near the hole was lime that helped reduce any noxious odors.

Each morning, Meaney awoke and followed a routine. He did some exercises, like partial push-ups, to stimulate his muscles. Breakfast and other meals were lowered down through the tubing. His one concession to comfort was a light, which he used to read the newspaper or books.

“I read anything,” he told a journalist while still in the ground. “It doesn’t matter what it is. Someone sent down The Financial Times, and I read that.”

Rather than a suit—the attire most often worn by decedents—he opted for blue pajamas and a crucifix. On day 31, Meaney celebrated the one-month mark with a glass of champagne. At one point, a reporter from the Associated Press lowered a camera down the tube so Meaney could take a selfie.

While plenty of onlookers visited and conversed with Meaney via a telephone receiver lowered into the tubing, the site wasn’t always monitored. Once, a truck backed up over the freshly-shoveled dirt, compressing it and threatening to crush both the coffin and Meaney. It was the only time, he later said, that he thought about calling it quits.

As there were no formal safety measures for being buried alive, lawmakers worried about what could happen if Meaney met his end. Inside the House of Commons, there was great debate over whether they should intervene and forcibly drag Meaney out. Despite some hand-wringing, they opted not to.

That wasn’t good news for Bill White, who, like Meaney, was testing his own will. Weeks passed, with both men becoming something of an art installation. If one kept traveling by their respective sites, it might have become almost mundane. Oh. There’s a man buried alive over there. Right.

Raised From the Dead

But Meaney wasn’t tiring. He lasted 40 days, then 50, then 55. At that point, he declared he could last another 45 days to make it an even 100. But Sugrue wasn't having it. He insisted Meaney come up after 61 days.

When the news hit Kilburn, spectators and reporters descended upon Keane’s Yard to witness Meaney’s return to the land of the living. It took workers roughly 30 minutes to remove the earth over him. With kilted Irish pipers playing, “pallbearers” took the coffin and began what amounted to a living procession. With thousands lined up along the streets, Meaney waved a dirt-encrusted hand through a hole in the lid.

When he finally emerged sporting a bushy beard and sunglasses to avoid the harsh glare of a sun he hadn’t seen in two months, Meaney was in remarkably good spirits. He was driven directly to The Admiral Lord Nelson Pub, where he had a beer.

His only complaint was the “talklessness,” a presumed reference to the lack of conversation while embedded in soil. Otherwise, “I feel wonderful,” he said. “I wanted to do 100 days more.”

Unfortunately, it wouldn’t have mattered much. To Meaney’s shock, no one from Guinness World Records had been in attendance for the stunt, which meant the organization couldn’t bestow any official acknowledgement of his feat—if it was indeed a record at all. Just days later, Bill White emerged from his own burial after lasting 62 days and 22 hours. Meaney’s accomplishment was almost immediately outdated. Nor could his fame be monetized: The News and Observer reported Meaney was to receive $24,000 for personal appearances in France, but by July 1968 Meaney declared that “I haven’t got a penny.”

Defeated, Meaney tried another ploy: Challenging Bill White in a burial-off. In May 1968, he threw down the gauntlet, inviting White to be buried at the same time as Meaney under 15 feet of concrete. There’s no report the event ever took place.

Despite the unwillingness of Guinness to recognize any of the dangerous stunts, voluntary burials continued. Later that year, 38-year-old Pat Haverland of Charleston, West Virginia, managed 64 days; former nun Emma Smith endured 101 days. Her son carried on the peculiar family legacy and managed 147 in 1999.

Though he was far from a world champion, Meaney dined out on the tale for the remainder of his life, becoming something of a local hero. He died February 17, 2003. Yes, he was buried. And yes, this time it was for good.