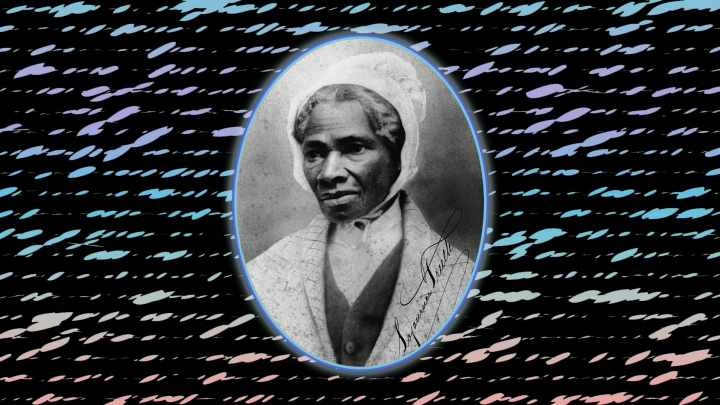

The Real History of Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman” Speech

Content Warning: This article includes the text of speeches that use outdated and offensive language and reflect stereotypes of Black Americans from the Civil War era.

In late May of 1851, activists assembled in a church in Akron, Ohio, for the Woman’s Rights Convention. The two-day event was a success, so crowded that standing room was hard to find. There were prayers, songs, coverage of topics like the state of women’s labor in America, and many a rousing address—among them one by Sojourner Truth that would come to be known as the “Ain’t I a Woman” speech.

The most famous account of the speech has shaped our conception of the circumstances surrounding Truth’s delivery of it and even of Truth herself. But it wasn’t printed until 1863, and earlier reporting on the convention—including another version of the speech published just weeks after the fact—tells a remarkably different story. In that version, the line “Ain’t I a woman?” doesn’t appear at all.

So which story should we trust?

The Flaws of Frances D. Gage

In spring 1863, The Atlantic published a feature on Sojourner Truth written by Harriet Beecher Stowe, which inspired activist Frances D. Gage to put her own memories of the abolitionist in print. Gage had been the president of the 1851 Woman’s Rights Convention in Akron, and so those memories revolved around Truth’s role in the event.

Gage’s personal essay, published in New York City’s weekly Independent and a handful of other papers that spring, alleged that women’s rights leaders circa 1851 were “staggering under the weight” of disapproval for the movement and wary of anything that could exacerbate the tension. According to Gage, many convention attendees were “almost thrown into panics” when Truth, a Black abolitionist, appeared on the first day, the implication being that linking feminist causes with abolition would spell doom for the former.

The second day was purportedly characterized by “long-winded bombast” from dissenters, “sneerers among the pews,” and an atmosphere that “betokened a storm.” As Truth rose to address the assembly, several people implored Gage to stop her, and “a hissing sound of disapprobation” echoed through the room. Truth then quelled the tension by delivering in “deep wonderful tones” a speech that elicited “roars of applause” and left “more than one of us with streaming eyes beating with gratitude.”

There is ample evidence to suggest that Gage may have exaggerated elements of this story for the sake of a compelling narrative. For one thing, none of more than two dozen contemporary accounts of the convention really corroborates it. Speaker Emma R. Coe described the event’s “spirit of harmony” with not “one discordant note,” and Cleveland’s Herald remarked on the lack of any “sly leer” or “half uttered jest” that readers might picture, especially given that men made up almost half the crowd. Even Gage contradicted herself: While speaking at a national women’s rights convention in 1853, she mentioned that “no one has had a word to say against us” at past conventions, Akron included.

It’s also worth noting that most women’s rights activists supported abolition, and the Akron convention had been publicized in abolitionist newspapers. Not to mention that Black abolitionists—including Truth and Frederick Douglass—had attended and occasionally spoken at previous women’s rights conventions. In short, it couldn’t have been much of a surprise or a scandal that Truth showed up to this one.

As for her treatment in Akron, it’s not hard to believe that white members may have afforded her, a formerly enslaved Black woman who couldn’t read or write, less warmth and enthusiasm than they did each other. Convention co-secretary Hannah Tracy later wrote that she “fear[ed] we did not feel ready to give her as royal a welcome as her merits deserved.” If Truth perceived anything from mild discomfort to outright enmity, though, she didn’t commit it to writing (that we know of). In fact, she expressed in a dictated letter to fellow abolitionist Amy Post that she “found plenty of kind friends, just like you, & they gave me so many kind invitations I hardly knew which to accept first.”

All that said, the most glaring sign that Gage embellished her account is the speech itself. She wrote it in a dialect associated with Black enslaved people in the South, and Truth had only ever lived in the North; she was born to enslaved parents in Ulster County, New York, and exclusively spoke Dutch for the first nine years of her life. If she had an accent, it was a far cry from the one Gage affected for her, and one widely circulated obituary described her diction as “grammatically correct” and her pronunciation “faultless.”

While there’s nothing incorrect about any way Black Southerners spoke English—an ever-evolving language with many dialects—Gage collapsed all Black Americans into a stereotype by giving Truth a dialect she herself didn’t use. The text is offensive to read, but it’s vital in understanding the extent of Gage’s fabrication.

Frances D. Gage’s Original Text of Sojourner Truth’s Speech

“ ‘Well, chillen, whar dar’s so much racket dar must be som’ting out o’ kilter. I tink dat, ’twixt de n******s of de South and de women at de Norf, all a-talking ’bout rights, de white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what’s all this here takling ’bout? Dat man ober dar say dat woman needs to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have de best places eberywhar. Nobody eber helps me into carriages, or ober mud-puddles, or gives me any best place‘; and, raising herself to her full height, and her voice to a pitch like rolling thunder, she asked, ‘And ar’n’t I a woman? Look at me. Look at my arm,’ and she bared her right arm to the shoulder, showing its tremendous muscular power. ‘I have plowed and planted and gathered into barns, and no man could head me—and ar’n’t I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man (when I could get it), and bear de lash as well—and ar’n’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen chillen, and seen ’em mos’ all sold off into slavery, and when I cried out with a mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard—and ar’n’t I a woman? Den dey talks ’bout dis ting in de head. What dis dey call it?‘ ‘Intellect,’ whispered some one near. ‘Dat’s it, honey. What’s dat got to do with woman’s rights or n*****s’ rights? If my cup won’t hold but a pint and yourn holds a quart wouldn’t ye be mean not to let me have my little half-measure full?’ and she pointed her significant finger and sent a keen glance at the minister who had made the argument. The cheering was long and loud. ‘Den dat little man in black dar, he say woman can’t have as much right as man ’cause Christ wa’n’nt a woman. Whar did your Christ come from?’

“Rolling thunder could not have stilled that crowd as did those deep, wonderful tones, as she stood there with outstretched arms and eye of fire. Raising her voice still louder, she repeated—

‘Whar did your Christ come from? From God and a woman. Man had not’ing to do with him.’ Oh! what a rebuke she gave the little man. Turning again to another objector, she took up the defence of Mother Eve. I cannot follow her through it all. It was pointed and witty and solemn, eliciting at almost every sentence deafening applause; and she ended by asserting ‘that if de fust woman God ever made was strong enough to turn de world upside down all her one lone, all dese together,’ and she glanced her eye over us, ‘ought to be able to turn it back and git it right side up again, and now dey is asking to, de men better let ’em’ (long continued cheering). ‘Bleeged to ye for hearin’ on me, and now ole Sojourner ha’n’t got nothin’ more to say.’ ”

There’s one detail in here that doesn’t match the historical record. Gage has Truth saying that she bore 13 children and saw most of them sold into slavery, but scholars generally agree that she was likely a mother of five, one of whom was sold into slavery.

If this were the only attempt at reproducing Truth’s speech, we’d have no way of knowing how much of it Truth actually uttered. Fortunately, it wasn’t.

What Marius Robinson Got Right

In spring 1851, married abolitionists Marius and Emily Robinson of Salem, Ohio—a few dozen miles from Akron—welcomed Truth as a houseguest. Both Robinsons participated in the Akron convention, Emily as a speaker and Marius as the recording secretary.

Marius was an editor of the Anti-Slavery Bugle, where he published his transcription of Truth’s speech on June 21, 1851. There is some overlap between his and Gage’s versions. In both, Truth declares herself equal to any man in terms of strength, appetite, and ability to work. She asks why women would be denied their pint of intellect by men who boast a quart; and she mentions that man had no part in the creation of Jesus Christ, who came from God and a woman. Truth also proposes that if God’s first woman was responsible for upsetting the order of the world, women should get a chance to right it.

A couple brief summaries of the speech in other newspapers back up these points and also lend credence to one detail from Gage’s version that Marius didn’t jot down—that Truth elicited laughter from listeners. No report, however, contains a single reference to Gage’s “Ar’n’t I a woman?” (which is most commonly rendered today as “Ain’t I a woman?”).

It’s not completely out of the question that Marius accidentally missed a line; he did say in his report that “It is impossible to transfer [the speech] to paper, or convey any adequate idea of the effect it produced upon the audience. Those only can appreciate it who saw her powerful form, her whole-souled, earnest gesture, and listened to her strong and truthful tones.”

But it is hard to believe that he would have missed “Ar’n’t I a woman?”. Not only was it his job to take notes, but scholars even think it likely that he ran those notes by Truth herself before printing them. Moreover, Gage has Truth saying “Ar’n’t I a woman?” four times.

“Had Truth said it several times in 1851, as in Gage’s article, Marius Robinson, who was familiar with Truth’s diction, most certainly would have noted it,” Nell Irvin Painter wrote in Sojourner Truth: A Life, a Symbol. “If he had an unusually tin ear, he might have missed it once, perhaps even twice. But not four times, as in Gage’s report.”

Marius Robinson’s Original Text of Sojourner Truth’s Speech

“ ‘May I say a few words?’ Receiving an affirmative answer, she proceeded; ‘I want to say a few words about this matter. I am a woman’s rights. I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? I have heard much about the sexes being equal; I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. I am as strong as any man that is now. As for intellect, all I can say is, if woman have a pint and man a quart—why cant she have her little pint full? You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take too much,—for we cant take more than our pint’ll hold. The poor men seem to be all in confusion, and dont know what to do. Why children, if you have woman’s rights give it to her and you will feel better. You will have your own rights, and they wont be so much trouble. I cant read, but I can hear. I have heard the bible and have learned that Eve caused man to sin. Well if woman upset the world, do give her a chance to set it right side up again. The Lady has spoken about Jesus, how he never spurned woman from him, and she was right. When Lazarus died, Mary and Martha came to him with faith and love and besought him to raise their brother. And Jesus wept—and Lazarus came forth. And how came Jesus into the world? Through God who created him and woman who bore him. Man, where is your part? But the women are coming up blessed be God and a few of the men are coming up with them. But man is in a tight place, the poor slave is on him, woman is coming on him, and he is surely between a hawk and a buzzard.‘ ’

The Woman, the Myth, the Legend

In the end, we can’t even really give Gage credit for making up a great line, misattributed though it (probably) was. As Carleton Mabee and Susan Mabee Newhouse pointed out in Sojourner Truth: Slave, Prophet, Legend, “Ar’n’t I a woman” was “undoubtedly an adaptation of the motto, ‘Am I not a Woman and a Sister?’, which had for many years been a popular antislavery motto.” That itself was a riff on “Am I not a Man and a Brother?”, a mantra of 18th-century British abolitionists.

For what it’s worth, Gage did write that her transcription was “but a faint sketch” of Truth’s oration. But that doesn’t make it clear that she filled in the blanks with her own flair—and when Gage’s version was reprinted in two seminal books, an 1875 edition of Narrative of Sojourner Truth and 1881’s History of Woman Suffrage, Volume 1, neither even included the disclaimer.

It’s especially interesting that Gage’s version is featured in Narrative, as Truth herself dictated the original 1850 edition and remained involved in the follow-ups. But she was evidently aware that in published reports of her life, the mythos of Sojourner Truth had begun to eclipse the facts: At an 1871 lecture in Syracuse, New York, she reportedly said that her life story “had growed and growed, and now it was a great book, and there wasn’t a word of truth in it, and what there was that was true was all hind side afore.”

With that in mind, it doesn’t seem so surprising that Truth never set the record straight on the exact syntax of one speech that she had given many years ago and maybe didn’t even remember word for word. That’s not to diminish the importance of preserving her speech as accurately as we can—and plenty of modern sources have platformed Marius Robinson’s version alongside Gage’s to give readers the whole story. The fact that it’s still widely called the “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech, though, is something we might just have to live with.

Learn About Other Famous Speeches:

manual