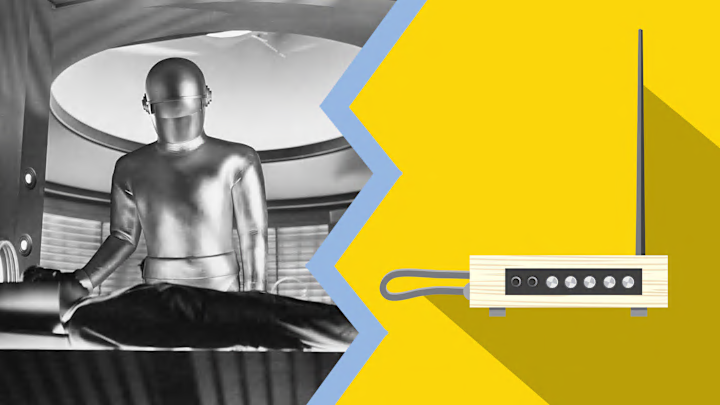

The eerie, futuristic tone of the theremin is unmistakable. In horror and science fiction, it may signal the arrival of a flying saucer, a character’s impending psychotic break, or a twisted science experiment gone wrong. The electronic nature of the noise suggests otherworldly origins, and its use in films like The Day The Earth Stood Still (1951) has made it synonymous with the uncanny and bizarre.

The instrument itself, however, is hard to recognize on sight. Consisting of a box with dials and two antennae—a vertical one extending upwards from the right side and a horizontal loop antenna sticking out from the left—it looks like a gadget built for experiments rather than musical compositions. In fact, that was the original intention when it was designed as part of a Soviet research program in 1919. Despite being invented in a laboratory by a physicist-turned KGB spy, it was only a matter of time before the theremin made it big in Hollywood.

It Came From Russia

Electricity was just starting to transform daily life in the early 1900s. Prior to the 1920s, less than half of U.S. homes had electrical power. Recordings of songs played on the radio, but the instruments used to play them were strictly acoustic. Silent pictures were still the norm at moviehouses.

It was in this climate that Leon Theremin created what would become the world’s first mass-produced electronic instrument. Born Lev Sergeyevich Termen in St. Petersberg, Russia, in 1896, he was a tinkerer from a young age. By 7 he could take apart a watch and put it back together, and by 15 he had built his own astronomical observatory. In his early twenties, the budding physicist was recruited by the newly founded Physical Technical Institute in Petrograd. As a student at the institution, Theremin conducted research into proximity sensors for the Soviet government in the wake of the October Revolution in 1917. His goal was to build a device that used electromagnetic waves to measure the density of gases, and could thus detect incoming objects. In trying to create that instrument, he instead created one that produced a whining sound similar to the thinner strings of a violin. When he moved his hand close to the machine, the pitch lept higher, and it dropped when he pulled his hand away.

Theremin was an experienced cellist as well as a physicist, and immediately saw the musical potential of his accidental invention. The burgeoning Soviet government saw its value as well, though it lacked military applications.

Electronic Espionage

Vladimir Lenin invited Theremin to the Kremlin to demonstrate his instrument—then known as the etherophone—in 1922. By moving his right hand along the vertical antenna to control the pitch and his left hand along the horizontal one to adjust the volume, Theremin performed Camille Saint-Saëns’s “The Swan” and other pieces for the Russian leader. Lenin was impressed enough to send him on a concert tour around the country.

The tour eventually extended to Western Europe. Theremin performed for Albert Einstein in Berlin in 1927, and the following year he brought the instrument to the United States, filling venues like Carnegie Hall and the Metropolitan Opera House with its ethereal music. The Soviet Union presented the world tour as a chance to show off its mastery of electric technology, but that wasn’t their only motive. Theremin was sent to the U.S. as a spy first and a musician second. His high status in his field granted him access to major American tech corporations like RCA, which signed a contract to manufacture his instrument for the mass market in 1929.

The company paid him $100,000 for the rights, but it would be a while before that investment paid off. The first commercial theremins cost $220—worth about $3700 today, and a prohibitively high price for many hobbyists. Because players controlled it by moving their hands through empty air, the learning curve was also steep. The Great Depression killed any hopes of it becoming an overnight sensation, and RCA suspended production.

The instrument’s inventor, meanwhile, was facing his own hardships. Despite the intelligence he gathered for his home country, Theremin wasn’t welcomed as a hero upon his return. The Soviet Union was in the midst of Joseph Stalin’s political purges, and in 1939, Theremin was arrested for alleged treason and sentenced to eight years in a Gulag for scientists, where he invented bugging devices and aircraft technology for the military.

Theremin’s days as a world-renowned concert performer were over, but the instrument that had adopted his namesake was just starting to take off on the other side of the globe.

The Sound of Science

The theremin made its cinematic debut roughly a decade after its invention. Dmitri Shostakovich became the first film composer to use it when he scored the 1930 Russian film Odna, or Alone. Instead of leaning into the instrument’s modern sound, he used it to evoke the howling Siberian winds the main character faces at the end of the movie.

In the 1940s, the unusual instrument was first featured in Hollywood film scores. Its association with sci-fi wasn’t immediate. In this decade, it was more often utilized in thrillers and mysteries to add an unsettling effect to scenes where a character experienced psychological distress. In Alfred Hitchcock’s 1945 movie Spellbound, composer Miklós Rózsa used the instrument to suggest mental instability when a white bathroom triggers the protagonist’s repressed memories of a skiing accident. The same composer also included it in his score for Billy Wilder’s The Lost Weekend, released that same year.

The theremin didn’t find its true niche until the 1950s. The decade was characterized by advancements in space exploration and anxieties about nuclear war—both of which helped fuel a golden age of science fiction in cinema. One of the earliest and most famous examples of the instrument in sci-fi is Bernard Herrmann’s score for The Day the Earth Stood Still.

In the 1951 movie, the electric squeal helped create a threatening and uncanny atmosphere around the alien invaders that couldn’t be achieved through costumes and special effects alone; countless alien and monster flicks that followed would borrow this same musical trick. By the end of the 1950s, the American public no longer viewed the theremin as a Soviet curio; it had become the official sound of outer space.

Retro Reputation

Though its cultural impact peaked in the mid-20th century, the theremin saw a brief resurgence in the 1990s. This was largely thanks to Tim Burton; the instrument adds a retro, B-movie vibe to the scores for his movies Ed Wood (1994), composed by Howard Shore, and Mars Attacks! (1996), composed by Danny Elfman. In Joel Schumacher’s Batman Forever (1995), Elliot Goldenthal used a theremin to compose the Riddler’s kooky mad scientist theme.

In each of these cases, the sound carried connotations it didn’t have 40 years prior. Instead of inspiring sincere dread, the high-pitched tone calls to mind an antiquated vision of the future popularized by low-budget sci-fi movies. A theremin can add a layer of nostalgia—or even ironic cheesiness—to modern media, but filmmakers can’t use it the way Alfred Hitchcock did in the 1940s and expect viewers to take them seriously.

More than a century after its invention, it’s clear that the instrument will always be associated with the 1950s sci-fi boom, even if its origins as a tool for Soviet espionage are just as interesting and bizarre.