Ron Wyden was visibly upset. The Democrat from Oregon was addressing a meeting of the House Energy and Commerce Oversight and Investigations Committee in July 1986 like a preacher on a pulpit, but his choice of accessory was not a Bible. It was a model plane kit.

“What I, as a member of Congress, am not even allowed to see is now ending up in model packages!” he said, brandishing a sleek hunk of plastic.

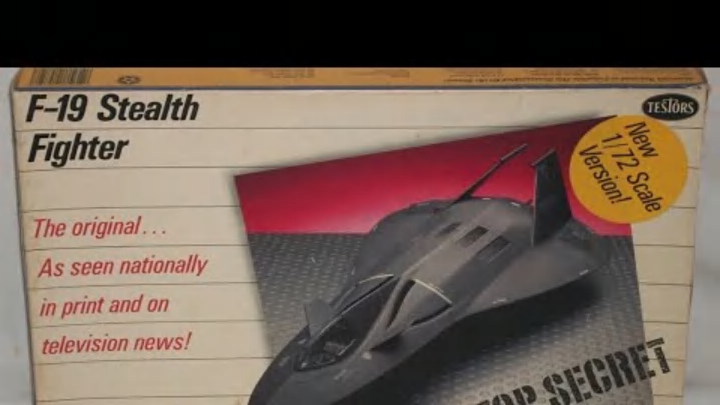

On the surface, Wyden’s complaint seemed bizarre. But this was no ordinary model kit. It was a 12-inch, 1:48 scale replica of a top-secret fighter plane dubbed the F-19 that had not been confirmed to exist by the Defense Department or the Air Force. Yet here it was on hobby shop shelves across the country. For a paltry $9.50, anyone—even Soviet intelligence—could get a glimpse of the U.S. military’s stealth fighter. All they needed was some glue and the patience to assemble its 66 pieces.

Like many observers, Wyden wanted to know how Testor, the company behind the model, could possibly know what this highly-classified project looked like. Somehow, a model toy was suddenly being eyed as a national security threat.

Off the Radar

Hobby model kits have their roots in the 1930s, when a British-based company known as FROG (Flies Right Off the Ground) began marketing planes crafted out of wood and metal that could achieve lift-off thanks to rubber bands. With the development of injection molding during World War II, plastic kits came into prominence, with companies like Revell, Monogram, and Aurora peddling everything from military vehicles to movie monsters. Though the elaborate box art often overpromised what the finished model looked like, the kits were popular with kids: One magazine survey conducted in the 1960s revealed that 99 percent of Boy Scouts built out the kits for fun.

Testor was one of the leaders in the model kit market. The company (sometimes referred to as Testors or the Testor Corporation) began in 1929 when Swedish immigrant Nils Testor acquired the assets of an adhesive business that peddled products to shoe cobblers. That soon led to a complete line of hobby materials, including paint, cement, and the kits themselves.

In 1969, Testor made headlines for devising a no-sniff glue to combat the trend of kids inhaling cement fumes for a fleeting high. The company added allyl isothiocyanate, or oil of mustard, a pungent and spicy scent that made huffing their adhesive highly unpleasant. (Testor suffered a brief slump in sales, as the additive angered glue-sniffers.)

But by the early 1980s, another problem arose: Kids were more preoccupied with video games than model planes, and sales across the industry dwindled. Few seemed interested in assembling a replica of a Sopwith Camel or B-52.

The industry needed a buzzworthy item: John Andrews provided it. A designer for Testor, Andrews was working on a sketch of a plane in the company’s San Diego office in 1985 when director of marketing Gary Cadish happened to walk by. Cadish was intrigued by a drawing of a sleek, futuristic-looking airplane that Andrews had done for an unrelated project. He wondered if it was based on anything in the real world. At the time, the Air Force was rumored to be collaborating with defense contractor Lockheed on the F-19, a stealth aircraft that could avoid radar and engage in missions without being detected. The project was a bit of an open secret: Jimmy Carter’s administration had confirmed such a project was underway in 1980, though no details or photos were made widely available.

“I could do a lot better,” Andrews told Cadish about his drawing’s accuracy. He said he could design one that was perhaps 90 percent true to the real thing.

The boast wasn’t so far-fetched. Andrews was an aviation buff and knew the rough appearance of the stealth fighter could be approximated based on some clever inferences from knowledge that was publicly available. The wingspan of the craft, for example, would have to fold up since Andrews knew from aviation trade journals that the plane had to fit in Lockheed’s C-5 cargo transport plane. The wheels would likely carry a wide tread due to the fact that the plane would have to be able to land on rough terrain. Having external missiles, Andrews knew, meant increased vulnerability to radar. And he also had a sketch given to him by a pilot friend who believed he had seen the F-19 in operation. That sketch, Andrews said, was too small and lacked detail, but it provided further evidence the plane existed. Still more information about radar-dodging craft came from a government-funded handbook.

Taken in isolation, the details weren’t much. But they added up to a clearer picture of what the Defense Department was hiding from public view.

Cadish was excited, but Testor president Chuck Miller was wary. After learning of the idea, he feared the company might be creating a national security threat by giving Soviets a look at U.S. technology at the height of the Cold War. Almost as worrisome was the fact that Testor would essentially be taking a shot in the dark at what the F-19 looked like. The company had a reputation among hobbyists for model kits based on actual blueprints of known aircraft, not guesswork.

Miller soon relented after hearing from Andrews, who assured him of reasonable verisimilitude and no obvious risk to military intelligence. The company also wrote to the Air Force and Lockheed informing them of their plans and that they would back off if told to do so. Neither organization responded, and so Miller told Andrews and Cadish to proceed.

Testor’s F-19 was ready for its debut at a January 1986 hobby show, where it was expected to take a backseat to the company’s major release that year: model kits based on the F-14 fighter planes seen in the Tom Cruise flight school drama Top Gun.

But then the plane crash happened.

Model Behavior

It’s possible Testor’s F-19 would have flown under the proverbial radar if not for the Associated Press, a news syndicate that picked up a story from a Dayton, Ohio, newspaper about the model kit and how it might resemble a project so secret that no official would go on the record about its existence.

“You can’t see it,” reporter Tim Gaffney wrote. “The Air Force won't talk about it. News reports about it have been sketchy and unconfirmed over the past several years. But if you want to build a plastic model of the super-secret stealth fighter, just place your order with the Testor Corp.”

Then, in July 1986, a story broke about a military plane that had crashed in Kern River Canyon in California. The Air Force declared the crash site a national security area and posted armed guards. The media speculated it was to protect the vaunted F-19. Since they had no images, they used Testor’s plane in their coverage.

It was free advertising. Sales skyrocketed, with hobby stores reporting sellouts of their stock; rumors spread that the kit was hard to find because the government was forcing Testor to recall it. (That wasn’t true.) Testor predicted they would sell 500,000 of the F-19 kits by the end of the year, far outpacing the 30,000 or so kits sold for an average release. (The number wound up being closer to 700,000, making it the bestselling model airplane of all time.)

Stories of Lockheed and government employees going into hobby stores to buy the kits were plentiful. So were confirmations that Russians were at least attempting to buy them in Washington, DC. (Stores there were sold out, too.) Reports of Soviet interest didn’t require any kind of security clearance: Russian intelligence often filled out embassy forms for purchases to avoid sales tax.

Testor fielded questions about how they could make a model for a plane that was supposed to be top secret. “We have no way of knowing whether such a plane exists,” Testor spokesperson John Dewey said. “Industry scuttlebutt has it that [the model is] reasonably close. This whole model is a guesstimate. It’s one step shy of sheer fantasy.”

The net result was terrific for Testor but grated on government. The F-19 was a so-called “black program,” which was developed without having to report to Congress. The covert nature was what angered Ron Wyden, who stood on the House floor with a Testor plane demanding to know why a model kit company seemed to know more about it than he did—a fact made more disturbing by Lockheed’s recent admission that some key documents were missing from their offices.

“Has our national security been compromised?” Wyden asked. “The fact is, we don’t know. We don’t know who’s got those documents, the Soviets, terrorists, model companies, who knows. That’s the danger.”

The Plane Truth

In 1988, the Air Force declassified the F-19—or at least what people thought was the F-19. Dubbed the F-117 Nighthawk, it was a stealth plane that had seen countless test flights and some action before the fleet was retired in 2008. (It was also never truly anti-radar: Instead, it appeared to radar operators more like a flock of birds.) Testor’s F-19 was a very rough approximation at best, sleek where the F-117 was angular—and, as Andrews had explained, never really a threat to national security. What made the F-117 novel was its internal components, not its external profile.

Andrews also maintained he had never seen any classified material, though he had built up contacts in the Defense Department as well as the aerospace industry—contacts that could, at least in theory, tell him if he was warm or cold.

Emboldened by their success with the F-19, Testor followed it up with a MiG-37B Soviet stealth fighter in 1987. One of their competitors, Revell, launched a F-19 bomber that same year. By that point, any hysteria over a model kit company sharing government secrets had died down.

But Testor wasn’t quite done. In 1994, the company released a UFO kit said to be based on eyewitness accounts of an extraterrestrial aircraft seized by the military and housed at Nellis Air Force Range in Nevada. Given Testor’s prior success with aircraft the government refuses to acknowledge, it makes one wonder if they weren’t on to something.

Read More About Toys: