As the 2002 holidays approached, the residents of a retirement home in Greater Vancouver started trotting out their most ostentatious Christmas sweaters. Employee Chris Boyd took notice.

“I would compliment them: ‘Wow, that’s an amazing sweater,’” he told HuffPost Canada. “In the back of my mind, I was thinking, ‘Wouldn’t it be kind of fun to track one of these down?’”

So he and his buddy Jordan Birch—whose elderly relatives favored similar sweaters—decided to throw a kitschy Christmas party at their friend Scott’s house in Coquitlam, a suburban city outside Vancouver. “The goal was to have the most cheesy, most feel-good party imaginable,” Boyd explained. Guests guzzled eggnog. They sang carols. They decorated a tree. And they did it all while wearing the flashiest sweaters they could scrounge up.

The pals made it an annual tradition, leveling up venues as the number of attendees increased; first moving to a university pub, then a local bar, and finally landing at Vancouver’s Commodore Ballroom, which hosted the event through 2017.

By that point, ugly Christmas sweater parties had become a full-fledged cultural phenomenon—one that Boyd and Birch are often credited with creating. But a deeper plunge into sartorial history suggests a slightly more nuanced narrative.

From Stripes to Ski Bears

People have been donning festive knitwear for the holidays since at least the Victorian era. An 1896 advertisement in The Boston Globe promoted Christmas sweaters “For Ladies, Men and Boys” (sorry, girls) in a “great variety of colors and striped effects.” In 1900, a West Virginia store advertised “Boys’ Christmas Sweaters in Fancy Stripes or Plain.”

It didn’t take long for the designs to transcend bright colors and basic patterns. The 1930s saw the rise of “jingle bell sweaters,” which turned the wearer into a walking, talking tintinnabulation. But there was nothing funny about them: Ad sketches showed elegant ladies and equally chic little girls flaunting tops with bells embroidered in dainty designs down the front. At most, a jingle bell sweater on a child might be considered cute; one in 1950, for example, depicted Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer with a tinkly jingle-bell collar.

This spirit of sincerity persisted throughout the back half of the 20th century, as Christmas became increasingly commercialized and the garments themselves grew more garish. You could argue that the sweaters of the ’60s at least tried to evoke the sophistication of their pre-war predecessors; Mad Men’s Betty and Don Draper certainly could’ve pulled off snowflakes and argyle without looking dowdy.

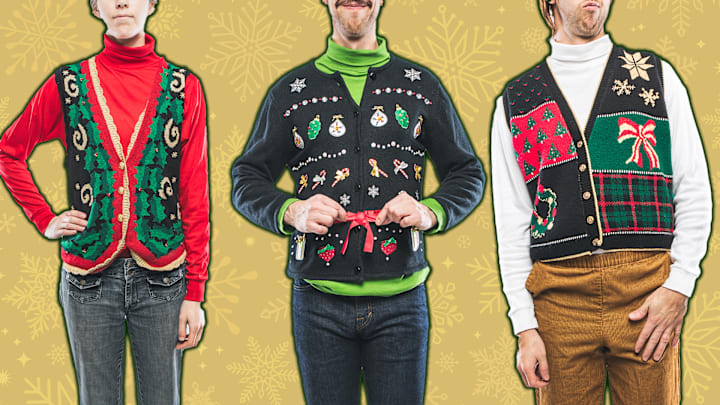

But any sense of restraint effectively died in the 1980s, when fashion and just about everything else fell victim to the mindset that more is more. Why select a sweater bearing only gingerbread men, or a gingerbread house, or a snowy vista, or a Christmas tree, or candy canes, or garland trimming, when there’s one that has it all?

The tackiness was endorsed by holiday entertainers like Andy Williams, whose get-ups of the ’80s and beyond were less staid than the solid-colored and simple-patterned sweaters he’d donned earlier in his career. Still, the marketing tone skewed earnest. A 1989 ad for Karen Scott sweaters, for example, promised “scenes that will warm her heart!,” from “ski bears” and ice skaters to snowmen and Santa Claus.

In the 1990s, however, a new paradigm emerged: Anyone bold enough to sport an ornate seasonal sweater during that decade was typically either in on the joke—or the butt of it.

You May Also Like ...

Add Mental Floss as a preferred news source!

For Sweater or Worse

The media often stereotyped those in the latter category as older women with an unabashed passion for Christmas and an utter lack of taste.

“It is our savior’s birthday, so why not have a blast?” one Alma Davis—whose sweater featured Santa, reindeer, and a battery-operated “Happy Holidays” banner—was quoted as saying in a 1995 Baltimore Sun story by Stephanie Shapiro.

Shapiro disparaged the craze, seemingly in shock over how many otherwise sensible women got decked out in “Scottie dogs on the rampage and gingerbread men run amok.” “They have the best intentions. But some how, some way, they must be stopped,” she wrote. “Christmas is becoming less a holiday than a disorder.”

Shapiro’s sentiments were echoed in later editorials by writers whose implicit misogyny shone brighter than any sequined Santa appliqué ever has.

“What drives a woman to wear something so cloyingly sweet, so annoyingly festive? Let me tell ya,” Hank Stuever wrote for The Washington Post in December 2001. That same month, The Hartford Courant’s Greg Morago penned a syndicated column (titled “Christmas sweaters a ho-ho-horrible sign of the season”) begging “Grandma … aunts, sisters and cousins” to forgo the tradition for fashion’s sake.

But plenty of Millennials had started to see the appeal of the cheerful, chunky knits—and it wasn’t just grandmothers and great aunts who stoked their interest. Ugly Christmas sweaters were featured in a few seminal comedies from that era, including 1994’s Dumb and Dumber and 2001’s Bridget Jones’s Diary.

In fact, Boyd and Birch have cited Dumb and Dumber as a key inspiration for their sweater shindig. So did Amos Templer, a native of Missoula, Montana, who hosted his first annual ugly Christmas sweater party with two roommates in 2001—predating the Vancouver duo’s by a year.

Ostentation Station

Over the next decade or so, as ugly Christmas sweater parties skyrocketed in popularity and thrift stores found themselves overrun with shoppers on the hunt for suitable attire, a cottage industry cropped up to meet the demand. In 2008, for instance, stay-at-home mom Anne Marie Blackman of Vermont started selling second-hand sweaters she’d embellished with everything from macrame Christmas trees and ornaments to plush. light-up reindeer.

What began as an eBay side gig became a whole company, My Ugly Christmas Sweater, and her products soon made appearances in commercials, on daytime talk shows, and more. Christina Aguilera once donned one of Blackman’s designs. And although large-scale retailers have since gotten in on the game, there’s still something exciting about sourcing a particularly hideous sweater from a homegrown operation.

Boyd and Birch’s viral success has in some ways propagated the assumption that they rescued the ugly Christmas sweater from the brink of extinction. But while they definitely did help popularize it among a surprisingly young demographic, the gaudy garb had never really disappeared. And the fact that Templer and company had the same idea just a season earlier negates the notion that credit belongs to any one person (or friend group).

Instead, you could argue that the 21st-century rise of the ugly Christmas sweater was merely the latest—maybe even fated—stage in an evolution that mirrors so many others in pop culture: the transition from unique and cool, to outdated and uncool, to retro and nostalgic—and, therefore, cool again, so long as your enjoyment is slightly tongue-in-cheek. But the next time you shrug on a lurid sweater heavy with baubles and bows and all the other Yuletide trappings, ask yourself this: At what point does “wearing it ironically” become just plain wearing it?

A version of this story originally ran in 2022; it has been updated for 2025.