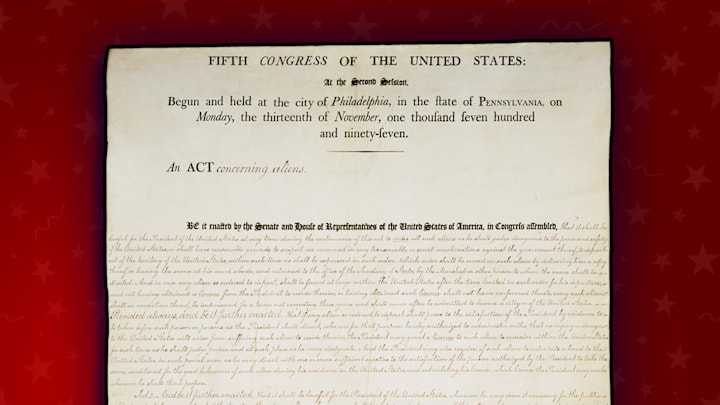

In 1798, President John Adams signed a series of four bills designed to safeguard national security in times of war. Known collectively as the Alien and Sedition Acts, they consisted of the Alien Act, Sedition Act, Naturalization Act, and Alien Enemies Act.

Although these laws continue to pop up regularly in contemporary political discourse, especially during national crises, their details often get lost in translation. Here are the essential facts about when they were created, how they were put to use, and why they have sparked fierce debates about civil rights and constitutional protections.

- Each act was designed with a specific purpose.

- The acts were passed during an undeclared war.

- The Alien and Sedition Acts polarized early American politics.

- The Alien and Sedition Acts were used to persecute Democratic-Republican critics.

- One drunk man was fined for an allegedly seditious joke.

- Debate around the Alien and Sedition Acts foreshadowed the Civil War.

- Accusations of sedition continued after Jefferson became president.

- Three out of the four Alien and Sedition Acts expired after the Quasi-War.

- Presidents invoked the Alien Enemies Act in subsequent (declared) wars.

- The Alien Enemies Act allowed for Japanese imprisonment during World War II.

- The Supreme Court has upheld the Alien Enemies Act’s legality.

Each act was designed with a specific purpose.

The Alien Act granted the president the authority to arrest, detain, and deport any non-citizen who was considered a threat to the country’s “peace and safety.” The Sedition Act criminalized the publication of “false, scandalous, and malicious writing” about the federal government. The Naturalization Act extended the residency requirement for U.S. citizenship from five to 14 years, while the Alien Enemies Act allowed the president to arrest, detain, and deport male citizens of hostile nations during “a declared war between the United States and any foreign nation or government, or any invasion or predatory incursion.”

The acts were passed during an undeclared war.

In 1794, the U.S. and Great Britain signed the Jay Treaty, officially titled the Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation. It established peace and economic ties between the U.S. and Britain following the American Revolution, a conflict that France had helped the U.S. win by financing and fighting in the war. The French government, seeing diplomatic relations grow between its ally, the U.S., and its longstanding enemy, Great Britain (with whom it was still at war), gave its navy permission to capture American merchant ships.

The Adams administration answered by preparing for a maritime conflict—which included the creation of the Alien and Sedition Acts. The tussle came to be known as the Quasi-War and lasted from 1797 to 1800. Because the war was never officially declared, it’s difficult to say exactly when it began. Most historians point to March 1797, when the French government set its navy loose on American merchantmen.

The Alien and Sedition Acts polarized early American politics.

The acts were initiated by members of the Federalist Party, which controlled both Congress and the White House at the time of the Quasi-War. President Adams, in signing the acts into law, claimed they were “war measures” necessary to safeguard national security during periods of armed conflict.

The Democratic-Republican Party, the yin to the Federalists’ yang, suggested there were other motivations: to crush dissent, restrict civil liberties, and empower the state. Attitudes towards the acts thus reflected the ideological differences between the two parties. The Federalists favored a strong central government run by elites, with close ties to Britain. The Democratic-Republicans, united under Vice President Thomas Jefferson, wanted the federal government to leave states and citizens alone as much as possible. They also supported the French Revolution as part of their ardent belief in self-determination.

The Alien and Sedition Acts were used to persecute Democratic-Republican critics.

While Adams never invoked the Alien Act or Alien Enemies Act to deport non-citizens throughout the Quasi-War, the Sedition Act enabled Federalists to persecute Democratic-Republicans critical of the incumbent party’s policies. The first person to be tried under the act, Vermont Congressman Matthew Lyon, was imprisoned after publishing a letter that accused Adams of trying to turn himself into a monarch using his executive powers to restrict free speech and other civil liberties enshrined in the Bill of Rights [PDF].

One drunk man was fined for an allegedly seditious joke.

Aside from targeting lawmakers and publishers, the Sedition Act was also used to silence ordinary Americans. Luther Baldwin, a garbage boat pilot from Newark, New Jersey, was fined $150 (about $3950 in 2025 dollars) after making an offhand remark during Adams’s visit to the city. Upon hearing a cannon salute, the intoxicated pilot shouted words to the effect of, “I hope it hit Adams in the arse!”

Debate around the Alien and Sedition Acts foreshadowed the Civil War.

In response to the trials, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, another prominent Democratic-Republican, drafted resolutions adopted by the legislatures of Kentucky and Virginia, respectively, declaring the Alien and Sedition Acts unconstitutional. While both sets of resolutions argued that the federal government had overstepped states’ rights to accept federal legislation, Jefferson’s went further, positing that because the Alien and Sedition Acts were thus unconstitutional, they were invalid.

In the years leading up to the American Civil War, Jefferson’s argument was picked up by Southern lawmakers like John C. Calhoun and Robert Hayne, who likewise argued that individual states had the right to disobey—and even break from—the federal government.

Accusations of sedition continued after Jefferson became president.

Public outrage over the Alien and Sedition Acts caused Adams’s approval rating to drop, contributing to his frenemy Jefferson’s victory in the 1800 presidential election. Although the Sedition Act expired before Jefferson took office, libel accusations continued to make their way to courts, this time with Federalists assuming the role of defendant.

One notable case, United States v. Hudson and Goodwin (1812), involved a Federalist newspaper that had republished an article accusing the Jefferson administration of misconduct. The case reached the Supreme Court, which ultimately ruled that federal judges could not prosecute crimes like seditious libel unless Congress passed a law that specifically authorized them to do so.

Three out of the four Alien and Sedition Acts expired after the Quasi-War.

The Sedition Act and Alien Act both expired after the undeclared naval conflict with France came to a close in 1800, and the Naturalization Act was repealed by Congress in 1802. Only the Alien Enemies Act remained in effect following the Quasi-War and is still a part of the United States Code to this day.

Presidents invoked the Alien Enemies Act in subsequent (declared) wars.

During the War of 1812 between the U.S. and Britain, which lasted until 1815, President James Madison invoked the Alien Enemies Act to impose travel restrictions on British citizens living in America. Throughout the war, these residents were required to report their whereabouts to state authorities and move away from coastal areas.

President Woodrow Wilson invoked the act during the First World War, establishing regulations that restricted the freedom of German and Austro-Hungarian citizens in the U.S. under the penalty of “summary arrest” and confinement in specially-erected war prisons in Georgia and Utah.

The Alien Enemies Act allowed for Japanese imprisonment during World War II.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt invoked the Alien Enemies Act to detain Japanese and Japanese American residents throughout the country. Even before the U.S. officially declared war against Japan, Japanese Americans were being arrested without warrants or criminal charges.

Historians estimate that the U.S. government incarcerated more than 120,000 people of Japanese descent over the course of World War II, many of whom were lawful U.S. citizens. Such residents were forcibly transported to remote camps in eastern California, Wyoming, Idaho, Arkansas, and other states. The government agency that ran the concentration camps where they were held, the War Relocation Authority, also detained people of Italian and German descent.

The Supreme Court has upheld the Alien Enemies Act’s legality.

The only time the U.S. Supreme Court has heard a challenge to the legality of the Alien Enemies Act was in 1948. The case, Lüdecke v. Watkins, concerned a member of the Nazi Party who had emigrated to the United States in 1934 and remained loyal to Adolf Hitler. The FBI arrested him in 1941.

The defendant, who was to be deported under the Alien Enemies Act after Germany’s surrender in 1945, argued the law could only be enforced during times of war. The Supreme Court disagreed, ruling that, though the war was indeed over, the remaining state of hostilities between the two nations provided adequate legal pretext. Instead of restricting the law’s applicability, the ruling broadened it.

Discover More Early United States History: