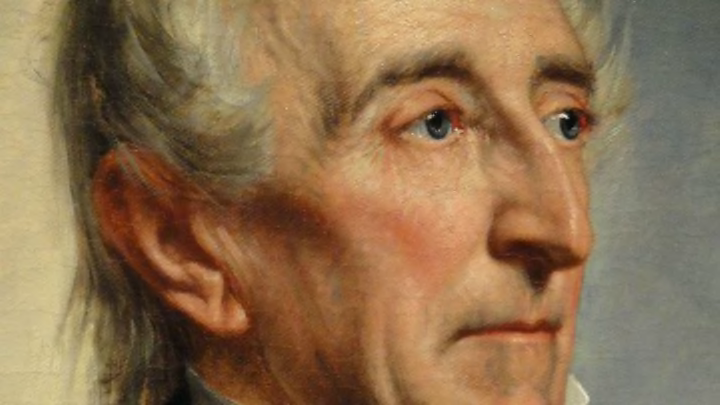

You know that John Tyler took over the presidency when William Henry Harrison died in 1841, but what else do you know about "Tyler Too?" Here are five things about our tenth president you might find interesting.

1. John Tyler set up presidential succession as we know it.

You probably remember from history class that Tyler ran for the vice-presidency with William Henry Harrison on the "Tippecanoe and Tyler Too!" slogan. You probably also remember that Old Tippecanoe lasted about a month in office before succumbing to an illness. Harrison's death brought up an odd situation for the federal government. For the first time ever, a president had died in office, and it wasn't entirely clear how the succession situation would play out.

Amid the confusion, Tyler declared that he had full presidential powers. He arranged to be sworn in and gave an inaugural address while downplaying any talk of being a "temporary" President. Although opponents dubbed Tyler "His Accidency," his rise to power would set the basic standard for presidential succession that would eventually be formalized in 1967 with the 25th amendment. Tyler's plan wasn't exactly the same as the one we have now, though; he spent the rest of his term without a vice president.

2. John Tyler wasn't a very popular president.

When you've got a nickname like "His Accidency," you're already working behind the 8-ball as a politician. That was actually the least of Tyler's problems, though. He had been elected as part of a Whig Party ticket, but his actual politics didn't always mesh well with the actual Whig doctrine. Tyler had strong states' rights leanings, and these beliefs made him butt heads with party bigw(h)igs like Henry Clay and Daniel Webster.

Thanks to these philosophical differences, Tyler earned a slew of dubious presidential firsts. When Tyler twice vetoed a national banking act that Clay was desperately trying to pass, the Whigs expelled him from their party, a definite first for a sitting president. Then, his entire cabinet except for Secretary of State Webster resigned in retaliation over Tyler's policies.

It gets better/worse, too. In 1842 Tyler's former allies introduced the first impeachment resolution against a sitting president over his use of veto powers. Representative John Quincy Adams led a committee that found Tyler had improperly used his veto, but the resolution failed. Congress had the last laugh, though; Tyler became the first president to have his veto overridden by the legislature when Congress overrode him on a minor ship-building bill on his last day in office.

3. John Tyler annexed Texas.

Texas declared its independence from Mexico in 1836, so for Tyler's term in office it was its own independent republic. (Mexico, though, still claimed the Lone Star State as part of its territory.) Tyler pushed hard for the annexation of Texas, and as his term was expiring in early 1845, the Senate finally approved a joint resolution in favor of annexation by a slim 27-25 margin. Tyler signed the Texas statehood bill into law on March 1, 1845, a mere three days before the end of his term. The city Tyler, Texas, is named after the president who helped get the state into the union.

4. One of John Tyler's grandchildren is still alive.

Tyler was born during George Washington's presidency, and his own stay in the White House ended in 1845. Yet somehow he still has one living grandson. How does that work? First, Tyler was, ahem, prolific. He fathered 15 kids, the most of any president. He didn't slow down in his golden years, either; his last child didn't turn up until Tyler was 70 years old. His son Lyon Gardiner Tyler was similarly active in his old age; Lyon fathered Harrison Tyler in 1928 at the ripe old age of 75. As of 2021, Harrison is still alive. His older brother, Lyon Gardiner Tyler, Jr., died in September 2020.

5. John Tyler died a traitor to the United States.

After Tyler's tumultuous presidency ended, his political career was pretty much shot. His 1862 obituary in The New York Times described Tyler as "the most unpopular public man that had ever held any office in the United States," and even that depiction might have been a bit charitable. Tyler did manage to maintain some popularity throughout the South, though, so when the Confederacy broke away at the start of the Civil War, Tyler found himself elected to the Congress of the Confederate States of America.

Tyler died in 1862 before he could take his seat, but running for a Confederate office severely hurt his stock in Washington. President Lincoln didn't issue a proclamation mourning Tyler's passing, and flags didn't dip to half-staff on federal properties. The Confederacy, on the other hand, threw a lavish funeral for Tyler in Richmond, including a 150-carriage procession.

Just how reviled in the North was Tyler when he died? Check out the penultimate paragraph of the aforementioned Times obit: "He ended his life suddenly, last Friday, in Richmond -- going down to death amid the ruins of his native State. He himself was one of the architects of its ruin; and beneath that melancholy wreck his name will be buried, instead of being inscribed on the Capitol's monumental marble, as a year ago he so much desired."

This story has been updated for 2021.