Before motion pictures, there were many ways for people to experience something they had never seen before. These visual extravaganzas, created by innovative and imaginative showmen, were often named using the Greek suffix -rama, meaning "a sight" or “view,” to help sell tickets to the next big thing.

1. Panorama

“Panorama,” or “all sight,” was first used by Robert Barker in 1792 to describe his almost 2700-square-foot, 360-degree painting of Edinburgh, Scotland. His panoramic technique, patented in 1787 as La Nature a Coup d' Oeil ("Nature at a glance"), required painting with a particular type of perspective that allowed the curvature of the picture to be taken into account so the image still looked correct when seen head-on. Barker’s panoramas were housed inside a cylindrical exhibit hall also called The Panorama. But as the concept caught on and panoramas popped up all over the world, the circular buildings soon became known as cycloramas, and were as widespread as our modern day movie theaters.

To view a panorama, audiences stood on a central platform under a skylight to ensure even lighting across the painting. To create a feeling of immersion, props such as tree branches hanging from the ceiling or rocks and shrubs on the floor, not only hid the edges of the painting, but also provided visual depth. It was this attempt to simulate reality that sparked criticisms as panoramas grew in popularity. Many, including poet William Wordsworth, witnessed audience members who became confused as to whether they were in the cyclorama or the actual place depicted in the painting. Some critics even compared the manipulation of panoramic paintings as destructive as wartime propaganda.

Although most of the thousands of panoramas that once graced cycloramas are gone today, a few still exist for public view. The most famous example in America is the Gettysburg Cyclorama, a 27-foot high, 359-foot-long painting depicting Pickett's Charge.

2. Diorama

Although we normally think of a diorama as a display in a museum or a shoebox science project, the original dioramas were nothing of the sort. In 1822, Charles Marie Bouton and Louis-Jacques-Mande Daguerre, who would later help revolutionize photography with the daguerreotype, built the Diorama Theatre in Paris to display paintings that, thanks to some clever light effects, seemed to come alive.

After paying for a ticket, audiences as large as 350 stood on a circular stage and looked down a long tunnel. At the end was a translucent, linen canvas 70 feet wide by 45 feet high with pictures painted on both sides. A well-rehearsed crew of workmen would strategically redirect outside sunlight at the front, back, and top of the canvas using screens, shutters, and colored gels, revealing the painting on either side of the canvas to create the illusion of movement or the passage of time. Sound effects were added to help complete the theatrical experience. After about 10 or 15 minutes, the theatre's floor would revolve on a giant turntable, redirecting the audience's view to a second tunnel showing a different diorama. In the Diorama, it was customary for one performance to be an interior scene, while the other would be an exterior. To help illustrate the concept, check out this amazing video:

Dioramas became very popular, with hundreds produced that traveled all over Europe. But only one original Daguerre diorama still exists today, on display at the church in Bry-sur-Marne, France. When the diorama was first installed, it consisted of three painted panels that made this small, simple church appear to contain large, ornate statues, as well as an extensive Gothic nave. When lit from the front and top by sunlight that shone through the building’s glass ceiling, the nave appeared to go on to a distant horizon. But as the light shifted, the church slowly descended into night, and the nave grew darker. Candles on the altar seemed to flicker in the drafty halls of this simulated cathedral. Sadly, the church has undergone architectural changes over the years, so the necessary glass panels and shades are no longer intact to make the diorama function as Daguerre intended.

3. Myriorama

If panoramic paintings were the movie theaters of their day, then myriorama cards were the televisions. Featuring slices of idyllic painted landscapes filled with people, buildings, flora, and fauna, a set of myriorama cards could be arranged in any order to create a seamless panorama on the parlor room table.

Although invented by Frenchman Jean-Pierre Brés in 1802, it was Englishman John Clark who really developed the idea and made it a popular British pastime in the 1820s. His first myriorama, or “many thousand views,” consisted of 16 cards, which, according to the advertisement, offered 20,922,789,888,000 variations of the landscape for only 15 shillings. His second series was 24 cards, making for an astounding 620,448,401,733,239,439,360,000 combinations.

4. The Moving Panorama

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, panoramas were the tops in entertainment. One innovation over the years was the moving panorama, a painting on a long roll of canvas that scrolled past an audience to simulate a journey.

One type of moving panorama was the pleorama, which took visitors on a virtual boat ride. Perhaps the most immersive of these was the Mareorama, featured at the 1900 Paris Exposition. Up to 700 guests at a time were taken aboard a replica steamship 100 feet long and about 30 feet wide, complete with smoking funnels and howling steam whistles, and manned by a captain and small crew. The ship was flanked on both sides by moving panorama paintings about 42 feet high and nearly 2500 feet long, for a total of about 210,000 square feet of canvas. The panoramas featured scenes from a sea voyage from Marseille to Constantinople, including many of the more exotic cities along the way. Thanks to special effects, day turned into night and back again, and the passengers even faced a high seas storm. To help complete the illusion, the ship was mounted on a 16-foot square iron frame that could be pitched and rolled by hydraulic cylinders, giving the sensation of rolling with the waves of the Mediterranean Sea.

Paris Exposition visitors could also “travel” on a padorama, a land-based transportation moving panorama, modeled after the then under-construction Trans-Siberian Railway. Passengers sat in one of three 70-foot railway cars that featured all the luxuries one could expect from first class accommodations during the golden age of the iron horse. Outside the windows, a multi-layered illusion of the landscape passed by. Closest were rocks and sand on a horizontal belt running at about 1000 feet per minute. Behind these props was a low canvas painted with shrubs that traveled at about 400 feet per minute. Just above this canvas was another, larger canvas with more distant scenery that ran at about 130 feet per minute. Finally, the largest canvas, at 25 feet tall and 350 feet long, displayed most of the mountains, forests, clouds, and famous landmarks like the Great Wall of China and Moscow’s St. Basil’s Cathedral. Because these images were off in the distance, this canvas passed by at a mere 16 feet per minute so everyone could get a good look. Although the actual journey by rail would have taken about 14 days to complete, audiences at the Exposition could complete their simulated trip in about an hour. The exhibit proved so popular that it was replayed at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis.

5. Cinéorama

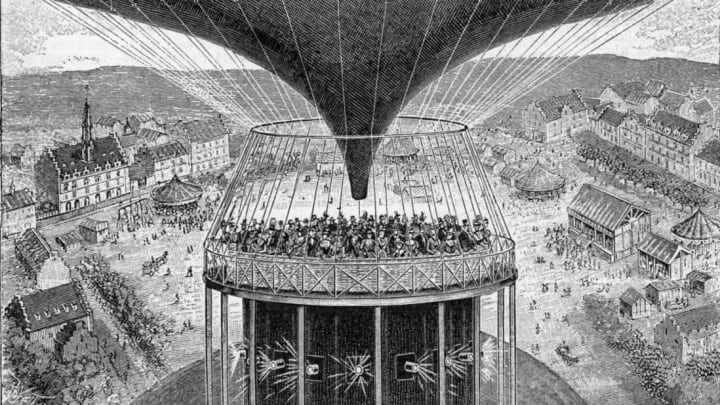

Like other ramas at the 1900 Paris Exposition, the Cinéorama by Raoul Grimoin-Sanson was a panoramic simulation ride, but with a turn-of-the-century high-tech twist. The ride consisted of a circular platform in the center of a cylindrical building large enough to hold about 200 paying customers. The platform was built to mimic a hot air balloon basket, complete with rigging ropes, sandbags, and a large balloon overhead that reached the ceiling. On the walls were ten 30-foot by 30-foot screens featuring a panoramic scene of the Tuileries Gardens in Paris created by ten synchronized 70mm movie projectors located below the viewing platform. The film depicted the balloon lifting 400 meters above the grounds, where it would hover for a few minutes to give the audience a good view, and then run backwards to simulate the balloon returning to the ground. The film was shot using a custom-built platform with ten cameras recording simultaneously, not unlike the multi-lens camera used for Google Streetview Maps today.

While the Paris Exposition lasted eight months, the Cinéorama only lasted three days—and some accounts say it never even had a debut performance. It was shut down because Paris police were concerned the intense heat generated by the projectors under the viewing platform posed a fire hazard. After the ride’s failure to launch, the company which Grimoin-Sanson created to manufacture and market the Cinéorama was bankrupt less than a year later. Gone, but not forgotten, Disney started using the same Cinéorama concept, now known as Circle-Vision 360, for many areas at their theme parks, including Epcot's O Canada! and America the Beautiful exhibits.