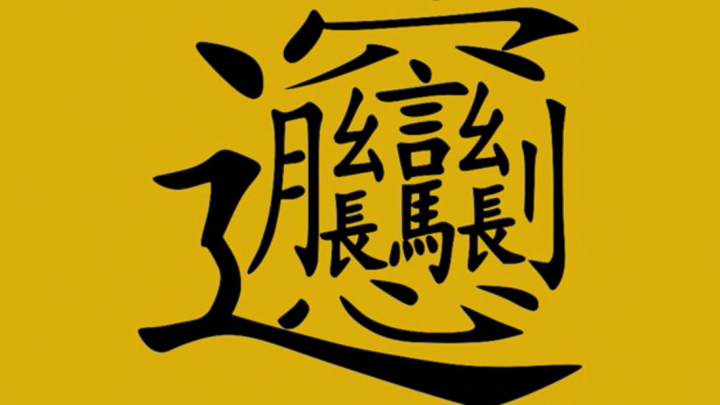

Chinese characters are made up of strokes. Learning to write them involves not only learning where all the strokes go, but also the order in which they are supposed to be written and the direction of each individual stroke (left to right, up to down, etc.) The simplest character is yī (one), a single stroke written from left to right. The most complex character, biáng (above), is made up of 57 strokes.

This character occurs in the written form of biángbiáng miàn, or biangbiang noodles, a dish of wide, flat noodles popular in the Chinese province of Shaanxi.

The status of biáng as most complex requires a bit of qualification. The character is not found in dictionaries, and its origin appears to be whimsical: biáng is not a syllable in Standard Mandarin but an onomatopoeia for the sound of noodles slapping on the table as they are being made, or for the lip-smacking sound of people contentedly munching on them. There are different theories about how the character came to be, but the most plausible one is that the owner of a noodle shop made it up.

If obscure or little-used characters count, then one could make a case for zhé, an obsolete character of 64 strokes, that, appropriately enough, meant "verbose."

Wikimedia Commons/Erin McCarthy

This character however, is just one single character (for long or "dragon") written four times. Biáng contains within it the characters for speak, horse, grow, moon, heart, knife, eight, roof, and walk, plus a few extra strokes, so though it might have fewer strokes, it has a lot more complexity.

For characters that do appear in modern dictionaries, the complexity winner seems to be nàng, a 36-stroke character referring to the sound your voice makes through a stuffed up nose.

Wikimedia Commons/Erin McCarthy

Biáng though, deserves to get the credit for its complexity. Though it is a highly atypical Chinese character, a case can be made for it being most "Chinese" of Chinese characters. As expert Sinologist Victor Mair says in this post at Language Log, "For me, biáng symbolizes the difficulty of accommodating the full fecundity of folk, popular, and local/regional cultures and languages within the bounds of the standard writing system, which enshrines the elite, high culture, and now also the bourgeois, urban, national culture. In other words, biáng is well-nigh bursting at the sides of the scriptal and phonetic boxes within which it is constrained."

Biáng. A local comfort food wrapped up, with a wink, in the ribbons of a 5000 year old writing tradition. A lip-smacking, calligraphical good time.