If this year’s Black Friday is like any other, too many people will crowd into stores and trample over each other to get a deal on some Christmas presents. People will get hurt. Someone might even get killed. These types of incidents, where a rush for goods can turn into tragedy, aren’t anything new. One of the most infamous—a stampede for toys in 19th century England—left 183 children dead.

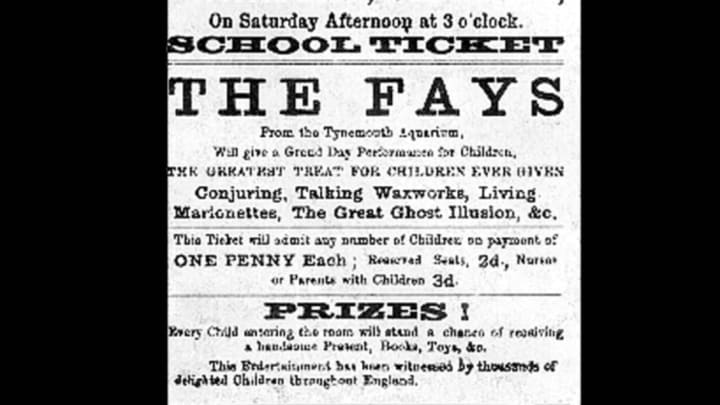

On June 16, 1883, the Victoria Hall in Sunderland, England hosted what was billed as the “greatest treat for children ever given.” The Fays of Tynemouth—“conjurer” Alexander Fay and his sister Annie the “enchantress”—had come to town to perform their variety show, featuring magic tricks, waxworks, “living marionettes” and their “Great Ghost Illusion.” Some 2000 tickets had been sold, and most of the seats were filled with children.

At the end of the performance, a special announcement was made: children holding certain numbered tickets would receive a free toy when they exited the hall, the Fays would distribute toys to other children from the stage and another man would take toys to the upper seating gallery.

When the kids in the upper gallery heard that, they “obligingly rose en masse and went down the stairs to meet him,” remembered William Codling, was six when he attended the show.

“I raced up the gallery as fast as I could, scrambled with the crowd through the doorway and jolted my way down two flights of stairs. Here the crowd was so compressed that there was no more racing but we moved forward together, shoulder to shoulder. Soon we were most uncomfortably packed but still going down.”

At the bottom of the stairwell there was a problem. The door to the arena had been partially opened and then bolted, leaving only a space of about two feet to squeeze through. Only one person could get through at a time; the door might have been jammed this way to control movement into the lower level and make ticket-checking easier. There was no staff at the door to organize a line, though, and the mass of kids coming from the gallery were flooding down the stairs and rushing the door. The first few children who got down the stairs managed to squeeze through the doorway, but as more and more came down the exit got blocked. The stampede didn’t stop and as the kids in the back kept pushing forward, those at the bottom, unable to open the door any wider, were trapped underneath the weight of the crowd.

“Suddenly I felt that I was treading upon someone lying on the stairs and I cried in horror to those behind, ‘Keep back, keep back! There’s someone down’,” Codling remembered. “It was no use, I passed slowly over and onwards with the mass and before long I passed over others without emotion. At last we came to a dead stop but still those behind came crowding on…”

“Children tumbled head over heels,” reported another witness. “The heap became higher and higher, until it became a mass of dying children over six feet in height.”

When the adults in the theater realized what was happening, they tried to pull the door open all the way, but the bolt was on the children’s side. Some adults ran up another staircase into the gallery to try and get the children still on the stairs to come back up.

“Then the pressure began to lessen,” Codling said. “A report spread that the toys were being distributed in the gallery and those behind having made a feeble rush upwards, back we tottered across that path of death. ... At the first landing we were met by some men and taken out of doors into the open air…Soon men began to come down the steps bearing in their arms lifeless burdens, and from the crowd came a wail of grief…”

In the end, 183 children between the ages of 3 and 14 died from being crushed and asphyxiated. Shock rippled through the whole country and a disaster fund raised 5000 pounds to pay for all the children’s funerals. Queen Victoria sent condolences to all the families and made her own donation to the funeral costs. Through the entire week that the funerals were held, businesses in Sunderland stayed closed as a sign of respect and mourning. The money that was left over from the fund was used to erect a memorial statue that stood in a park across from the hall, which was leveled during a German air raid during World War II.

Parliament made two investigations into the Victoria Hall disaster, but failed to find who was responsible for bolting the door the way that they did. The tragedy did result in some good, though; the government issued new laws that required “places of public entertainment” to have a sufficient number of exits with doors that could easily open outward, leading to the development of the push-bar emergency exit.