Shakespeare’s life is as full of fiction as his plays are. In fact, historians have taken decades to separate the legends and bawdy stories from fact. Some of the juiciest tales are now debunked, while others are new theories to fill in the holes in his biography. Here are five “to-be-or-not” stories of the bard.

1. Shakespeare stole a powerful man’s deer

The story goes that while still home in Stratford, the newly married Shakespeare was caught stealing deer belonging to Stratford bigwig Sir Thomas Lucy. Questioned and whipped by Lucy himself, Shakespeare felt so much shame he fled to London and became an actor. This scandalous tale was an accepted fact for centuries. Who wouldn’t want to believe Western literature’s greatest name started as a disgraced thief?

But while the Lucys did keep deer, scholars now find no evidence of this escapade, though four different biographers have repeated it. Most likely, it began as a rumor in the 17th century to explain why Shakespeare would leave predictable, comfortable, stuck-in-a-rut Stratford for the excitement of London.

2. Shakespeare stole his best actor’s girl

Richard Burbage was Shakespeare’s most celebrated actor, playing most of their company’s leading roles. Along with his father, Burbage provided his company with two theaters—the Theater and the more famous Globe—but that apparently didn’t stop Shakespeare from stealing his woman.

According to historical rumor, after a performance of Richard III—with Burbage in the title role—a young fan invited the actor to visit her secretly and to announce at her door, “Richard the third has come.” Shakespeare overheard the plan and raced to the lady’s room. When Burbage arrived and announced himself as told, Shakespeare sent word down that “William the Conqueror came before Richard the third.”

Shakespeare may well have scooped up women from Burbage, but nothing supports this story being more than legend.

3. Shakespeare was godfather to his own illegitimate son

Long after Shakespeare’s death, Restoration-era playwright William Davenant was one of four men commissioned in the 1660s with interpreting and adapting his works. To Davenant, born 1606, this was preordained: Publicly, Shakespeare was his godfather, but Davenant claimed just as publicly that they were actually father and son.

Shakespeare was close to the Davenants. William said he learned how close in a roundabout way at school. The Davenants lived in Oxford, where Shakespeare sojourned when on his way to visit his family in Stratford. Young William was summoned once from school to meet him. Questioned on the way by a teacher, William said he hurried to see his godfather. The teacher quipped that William should know better than to use God’s name in vain. William claimed to have been named after Shakespeare and maintained he wrote with his supposed father’s “very spirit.”

The most vocal supporter of this genealogy was—guess who—William Davenant. There was no real proof that he was Shakespeare's son. How claiming that he was helped his career can only be guessed, but were you ever forced to read William Davenant in school?

4. Shakespeare was God’s own spy

Shakespeare’s plays are full of conspiracies, even the comedies. The idea that he didn’t just write conspiracies but lived one as well is an enticing theory of his early life. Was young Shakespeare a reluctant Catholic spy? Shakespeare historian Stephen Greenblatt imagines so.

Queen Elizabeth I made a show of persecuting Catholics early in her reign. Will’s father John, as a Stratford official, was responsible for the destruction of the altar of Stratford’s Catholic chapel. But John was also a secret Catholic. During renovations to the Shakespeare family home in the 18th century, a book was found in the rafters: a “spiritual declaration” of the Catholic faith signed by John, with space for other names, and prepared by Jesuit priest Edmund Campion, executed for treason in 1581.

Greenblatt suggests this and other passing affiliations with Campion pushed the young Shakespeare into carrying messages between Catholic priests hidden near Stratford. These jaunts brought William close to 26-year-old Anne Hathaway.

Both parents deceased, Anne was very available. Did she provide Shakespeare with a release from the intrigue forced on him?

They married quickly in 1582. William was 18. Anne was pregnant, so there’s also that. She was left in Stratford while Shakespeare played around in London, suggesting the whole affair was born out of youthful rebellion. But until the sonnet “I was a teenage anarchist” shows up—which would definitively prove Shakespeare’s role in an actual latent rebellion—this lies squarely in conjecture.

5. Shakespeare ruled all of England

Did Shakespeare, a glove-maker’s son from Stratford, really shake up the Elizabethan theater scene? Many historians question whether Shakespeare was a pseudonym or even a complete invention overall. A dozen names have been put forth as the real Shakespeare—most strangely, the martyred Edmund Campion. Let’s go with the best: Shakespeare was really Queen Elizabeth I herself. I know, right?

In his book Players: the Mysterious Identity of William Shakespeare, writer and entertainment lawyer Bertram Fields admits the Queen is an outside bet. Her breeding gives her the education needed to plot those histories and tragedies, and certain sonnets could contain clues she meant to leave. Then again, would she have written scenes she publicly found abhorrent and, as Fields points out, suppressed or deplored them?

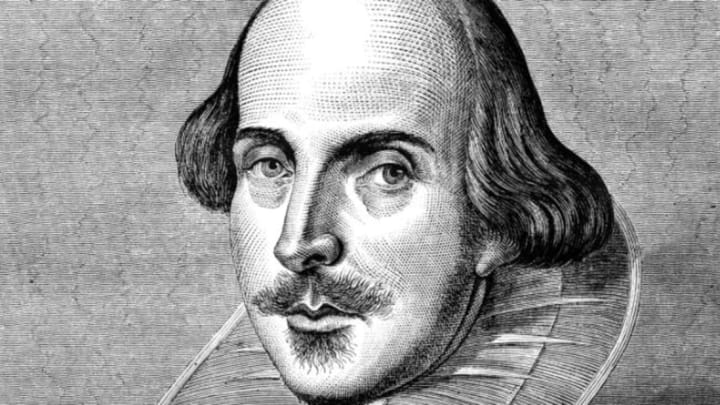

Other (flimsy) evidence lies in Shakespeare’s portrait included in the first publication of his plays, called the First Folio. Under computer imaging, Shakespeare without his beard is supposedly a dead ringer for the Virgin Queen—if that portrait really is Shakespeare; it was done seven years after his death. Still doesn’t bode well for Anne Hathaway. But it would make a hell of a story for William Davenant.