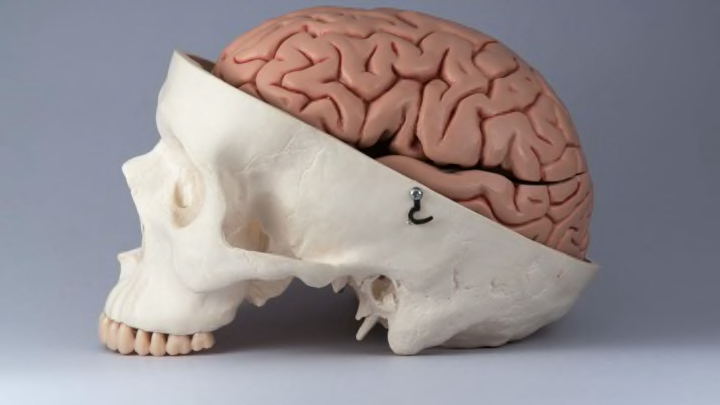

The inner workings of the brain are one of biology's greatest mysteries. There is much that scientists don’t fully understand about the most complex organ in the human body, from how we store memories to why we sleep and dream.

They're slowly chipping away at its secrets, though. Researchers from Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School have discovered the existence of tiny tunnels connecting the skull and the brain in both humans and mice, according to Science Alert. The findings, published in the journal Nature Neuroscience, reveal how immune cells take a “shortcut” by traveling through these tunnels to get to the brain in the event of a stroke, meningitis, injury, or other disorder affecting brain function. The cells, which help to reduce inflammation, were previously thought to move through the bloodstream.

Prior to this study, researchers didn’t know whether these cells, a type of white blood cell called neutrophils—which help the body defend itself against infections like meningitis—originated in the skull or in the tibia (a.k.a. the shin bone). Using membrane dyes that were injected into the cells of mice, researchers were able to track these cells and see where they traveled.

It was determined that more neutrophils were coming from the skull than the tibia, and upon closer inspection, researchers learned that they were traveling through microscopic channels that link bone marrow in the skull with the outer lining of the brain. Next, the researchers took pieces of a human skull to determine if the same concept applies to our anatomy. Lo and behold, the channels were indeed visible—and they’re five times larger than the tunnels found in mouse skulls.

Scientists say further research is needed, but believe the findings could help improve their understanding of how certain diseases affect the brain. The next step: investigating the role these tunnels play in responding to acute stroke, hypertension, Alzheimer’s disease, and other ailments.

[h/t Science Alert]