Adolescents aren't the only ones who suffer from acne. Some of Georgia O'Keeffe's paintings from the '40s and '50s have also sprouted a few "pimples" as well, according to Smithsonian.

These tiny bumps that bubble up on the surface of artworks go by different names—including "pimple-like protrusions," "blisters," and "art acne"—but everyone pretty much agrees that they're undesirable. O'Keeffe herself noticed the bumps while she was still alive, but for decades, conservationists and art scholars thought they were merely grains of sand. This wasn't a bad theory, considering that O'Keeffe lived and worked in the New Mexico desert.

However, a team of experts from Northwestern University and the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe recently discovered that the problem is a little more complicated. As it turns out, these pimples are caused by a chemical reaction known as metal carboxylate soaps.

"The free fatty acids within the paint's binding media are reacting with lead and zinc pigments," Marc Walton, a professor of materials science and engineering at Northwestern, said in a statement. "These metal soaps started to aggregate, push the surface of the painting up and form something that looks like acne."

Practically all of O'Keeffe's paintings are plagued by these metal soaps, but her pieces are hardly the only ones. The works of Vincent van Gogh, Rembrandt, Piet Mondrian, and Marc Chagall have also shown signs of "breakouts," as Smithsonian puts it. By some estimates, up to 70 percent of all the world's paintings on public display suffer from the affliction.

While these bumps are sometimes hard to detect with the naked eye, they are destructive and can get worse over time. Even when conservators restore the paintings, the lumps often return with a vengeance.

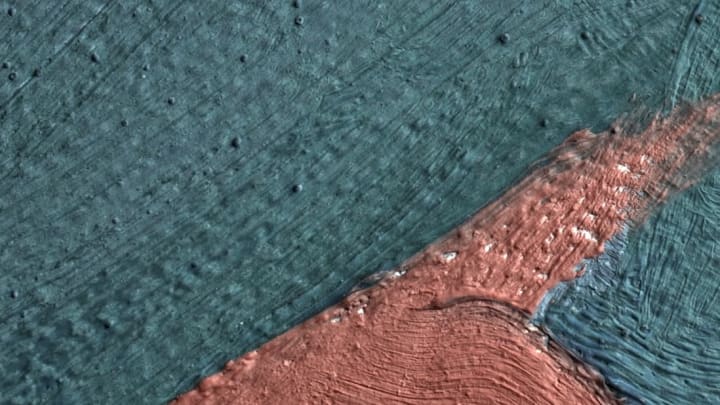

Fortunately, the team of experts developed an app that lets museum staff turn their smartphones and tablets into a hand-held tool that's capable of monitoring the growth of these pimples. Essentially, the app uses the flash or LED display to reflect light off the painting and capture it in an image. Those photos then get filtered through algorithms that are designed to identify the shape of the surface—including any problem areas. Oliver Cossairt, an associate professor of computer science, likened the smart tool to the "tricorder" from Star Trek, which was used in part to diagnose disease. "It can give you extremely accurate measurements but is also something you can just pull out of your pocket," Cossairt said.

The app is still being tested, but researchers hope to make it available to the public in a year. For conservators, having access to better—and cheaper—measurement tools will help them identify a course of action to protect these artworks, whether it's tweaking the storage conditions or improving the travel containers that carry pieces from one exhibit to the next. "If we can solve this problem, we’re preserving our cultural heritage for generations to come," Walton said.

[h/t Smithsonian]