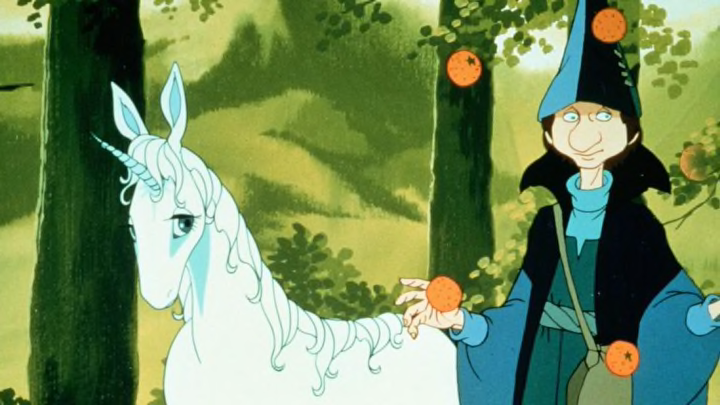

It’s been nearly 40 years since The Last Unicorn (1982) reared its magnificent, horn-adorned head in theaters across America. For adults, the animated Rankin/Bass production was a highly innovative, surprisingly introspective film with all the trappings of a quality fantasy, from its magical, motley, quest-bound crew to every winding staircase in its towering castle. For those who watched the film as a kid, on the other hand, The Last Unicorn was a 90-minute nightmare complete with a screeching, three-breasted harpy; a fiery, diabolical bull; and music sung by your chillest uncle’s favorite band.

Rediscover the enchanted world of the cult classic with the following facts—and keep a wary eye out for beasts, brutes, and Mommy Fortuna.

1. The Last Unicorn was based on a book by Peter S. Beagle, who also wrote the screenplay.

Peter S. Beagle published his fantasy novel The Last Unicorn in 1968, and also insisted on writing the screenplay when it was optioned for film. That resolution coming from another novelist might’ve made film executives a little apprehensive, but it wasn’t Beagle’s first time at the screenwriting rodeo: he had also written the screenplay for Ralph Bakshi’s 1978 film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings.

“I had the horrors about who else might do it,” Beagle said in an interview. “I never felt I had a choice, whether I particularly wanted to do the screenplay or not.”

2. The Last Unicorn was originally intended for an adult audience.

It’s not just the frightful red bull and permeative sense of terror that make The Last Unicorn seem like a questionable film to show young, impressionable children—there’s also a rather scarring scene in which a lascivious old tree holds Schmendrick captive with her ample bosom. (Not to mention that most of the music was performed by the legendary ’70s folk rock band, America—not quite a kindergarten favorite.)

The overall adult tone is much less odd when you consider that it was, at least initially, intended for adults. Early press referred to the film as an “adult musical fantasy-adventure” and also mentioned that Rankin/Bass had deliberately cast actors who would pique adult interest.

3. The creators of the Peanuts TV specials wanted to make the film.

Lee Mendelson and Bill Melendez, the producers behind A Charlie Brown Christmas, A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving, and many other Peanuts TV specials, were very interested in adapting the novel for film, though nothing ever came of it. By Beagle’s own account, one of their partners’ wives pulled him aside at a gathering and earnestly cautioned him against entrusting the project to them.

“Don’t let us do it. We’re not good enough,” Beagle recalled her warning him.

4. Nobody turned down the opportunity to be cast in The Last Unicorn.

The project eventually went to Jules Bass and Arthur Rankin, Jr. of Rankin/Bass Productions, the company best-known for its stop-motion animation projects like Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, Santa Claus Is Comin’ to Town. As a testament to both the popularity of the novel and the quality of the screenplay, Rankin and Bass weren’t forced to settle for their second choices for any of the voice actors.

“We decided to get the best people we could get,” Bass said in an interview. “And one thing that’s interesting about it, and this is unique, is that every single person whom we approached to do it said yes immediately.”

Those “best people” included Hollywood heavyweights and musical theater legends alike: Mia Farrow as the titular character, Alan Arkin as Schmendrick the magician, Jeff Bridges as Prince Lir, Christopher Lee as King Haggard, Angela Lansbury as Mommy Fortuna, Tammy Grimes as Molly Grue, and more.

5. Jeff Bridges personally asked for a role—and even said he’d work for free.

After hearing that René Auberjonois, his friend and fellow actor from 1976’s King Kong, had been cast as a cackling skeleton in The Last Unicorn, Jeff Bridges called Bass and asked if he could be involved, too. When Bass told him they had yet to cast Prince Lír, Bridges volunteered to lend his time and talents either for free or for whatever Auberjonois was making. Bass hired him on the spot.

6. Prince Lír has a happier ending in the book version of The Last Unicorn.

In the film, Prince Lír leaves the kingdom to forge a new life for himself after losing just about everything: his adoptive father has died, the castle he should’ve inherited has crumbled into the sea, and his beloved Amalthea has transformed back into a unicorn. In the original novel, however, Lír remains to rebuild the kingdom, and he even gets a second chance at love: When Schmendrick and Molly happen upon a troubled princess (fully human, this time) during their journey, they send her Lír’s way.

7. The Last Unicorn was animated by the studio that would later become Studio Ghibli.

Though the original storyboards for The Last Unicorn were created in the U.S., Rankin/Bass outsourced the film’s actual animation to the experts at Topcraft, a Japanese animation studio with whom they had already collaborated on The Hobbit and many other productions throughout the 1970s. When Topcraft folded a few years later, the company was bought by Hayao Miyazaki, Isao Takahata, and Toshio Suzuki, who rebuilt it as Studio Ghibli and went on to release some of the most celebrated animated features of all time, including 2001’s Spirited Away and 2004’s Howl’s Moving Castle.

8. Peter Beagle wasn’t thrilled with Alan Arkin’s performance.

Overall, Beagle has expressed satisfaction with how the movie turned out, commending the animators’ “lovely design work” and calling the voice actors “superb.” One actor, however, did fall short of Beagle’s expectations: Alan Arkin, who voices the affable yet blundering magician, Schmendrick.

“I’m still a little disappointed with Alan Arkin’s approach,” Beagle said in an interview. “His Schmendrick still seems too flat for me.”

(The word schmendrick, by the way, is Yiddish for “a foolish, bumbling, or incompetent person.”)

9. Christopher Lee also played King Haggard in the German version of The Last Unicorn.

Christopher Lee was a fierce supporter of both the film and novel, and considered King Haggard a tragic, rich character similar to Shakespeare’s King Lear. Such was his enthusiasm for the project that he even signed on to reprise his role for the German dubbing of the film (he was fluent in German). According to Beagle, Lee said he “simply couldn’t resist a chance to play King Haggard one more time, even in another language.”

10. German audiences love to hear America perform “The Last Unicorn.”

Evidently, it wasn’t just Christopher Lee’s acting chops that helped establish a German fan base for the The Last Unicorn—it was also the music, composed by Jimmy Webb and recorded by America. Bandmember Dewey Bunnell said in an interview that they often play the title track while touring there, since German audiences love to hear it.

11. Art Garfunkel and Kenny Loggins have both covered songs from The Last Unicorn soundtrack.

A couple of America’s contemporaries have given their own folk rock treatment to songs from The Last Unicorn soundtrack: “That’s All I’ve Got to Say” is the final track on Art Garfunkel’s album Scissors Cut, and Kenny Loggins sang “The Last Unicorn” for Return to Pooh Corner in 1994.

12. Fergie wanted to adapt The Last Unicorn for Broadway.

In 2015, Playbill announced that the Black Eyed Peas’s Fergie, a childhood fanatic of the film, was planning to bring The Last Unicorn to Broadway with the help of then-husband Josh Duhamel. There hasn’t been any news of it since, and, considering Fergie split with Duhamel in 2017, it’s probably safe to say that the project is on hold.