Seven score and 17 years ago, Abraham Lincoln uttered fewer than 280 words in front of Union mourners at the site of the Battle of Gettysburg. Brief as it was, the Gettysburg Address captured the democratic spirit of the nation and galvanized the North to redouble their efforts in the Civil War.

Read on to learn more about the speech that originated the phrase “government of the people, by the people, for the people” and taught us all that longer doesn’t always mean better.

1. Abraham Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address at the dedication of the National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

The Union triumphed over Robert E. Lee’s Confederate forces at the Battle of Gettysburg—often considered the turning point of the Civil War—in July 1863, but both sides suffered grievous losses. Townspeople formed a committee to replace more than 3500 temporary battlefield graves with a national cemetery, and committee leader David Mills invited Abraham Lincoln to deliver “a few appropriate remarks” at the dedication ceremony on November 19. Though Lincoln spoke for just two minutes, his 272-word Gettysburg Address remains one of the most famous speeches ever delivered.

2. The Gettysburg Address wasn’t the main speech of the event.

The star speaker of the ceremony was Edward Everett, a former Harvard president, U.S. congressman and governor of Massachusetts, and Millard Fillmore’s secretary of state. Everett lived up to his reputation as the greatest orator of the time with an epic, impassioned two-hour speech that he delivered from memory. But he, too, was impressed with Lincoln’s concision.

“Permit me also to express my great admiration of the thoughts expressed by you, with such eloquent simplicity & appropriateness, at the consecration of the Cemetery,” he wrote to Lincoln in a letter the following day. “I should be glad, if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.”

3. Abraham Lincoln probably didn’t write the Gettysburg Address on the train.

Legend has it that Lincoln hastily scrawled his brief speech on the back of an envelope on the train ride from Washington, D.C. to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. However, one copy was partially written on official White House stationery, leading experts to believe that Lincoln worked on his speech before leaving home and finished it the night before the ceremony. Also, the bumpy train rides of the 1860s would have affected Lincoln’s handwriting, and both of his early manuscripts are written in his characteristically neat, even script.

4. Abraham Lincoln may have had smallpox when he delivered the Gettysburg Address.

On the train ride to Gettysburg, Lincoln reportedly told one of his private secretaries that he felt weak, and his health deteriorated rapidly in the days after the speech. In 2007, researchers at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston studied the symptoms of his mysterious illness—which included high fevers, headaches, backaches, and scarlet blisters all over his skin—and suggested that he had actually suffered from a life-threatening case of smallpox. Fortunately, Lincoln made a full recovery, and resumed his regular presidential duties three weeks after falling ill.

5. The Gettysburg Address has similarities to Pericles’s funeral oration from 431 BCE.

In 431 BCE, Athenian statesman Pericles delivered a rousing speech to commemorate those who had already perished in the Peloponnesian War (which would last for nearly 30 more years). Not only do both speeches honor the soldiers’ sacrifice, but they also recognize those who came before them, emphasize equality in the eyes of the law, and encourage the surviving citizens to continue to fight for the greater good.

6. Not everyone loved the Gettysburg Address at the time.

Though many Union supporters and Republicans praised Lincoln’s carefully chosen words, Democrats and other skeptics did nothing to hide their derision—in fact, certain publications practically shouted about it. The Chicago Times said that “the cheek of every American must tingle with shame as he reads the silly flat dishwatery utterances of a man who has to be pointed out to intelligent foreigners as the president of the United States,” and Pennsylvania’s Daily Patriot and Union recommended that the nation never repeat or think about “the silly remarks” ever again. Even the Times of London thought the ceremony “was rendered ludicrous by some of the sallies of that poor President Lincoln.”

7. There are five known manuscript copies of the Gettysburg Address.

The two early manuscripts that Abraham Lincoln entrusted to his private secretaries, John Nicolay and John Hay, are both housed in the Library of Congress. Sometime after he delivered the speech, Lincoln penned three more copies. One was for Everett, which is now kept at the Illinois State Historical Library; another, now at Cornell University, was requested by historian George Bancroft; and a third, for Bancroft’s stepson, Colonel Alexander Bliss, now lives in the Lincoln Room of the White House.

The five manuscripts differ slightly, and so do people’s opinions on which one is considered standard. Some prefer the Bliss copy, since it was Lincoln’s final draft and also the only copy he signed, while others think the Associated Press transcription from the actual event is a more accurate version of the speech.

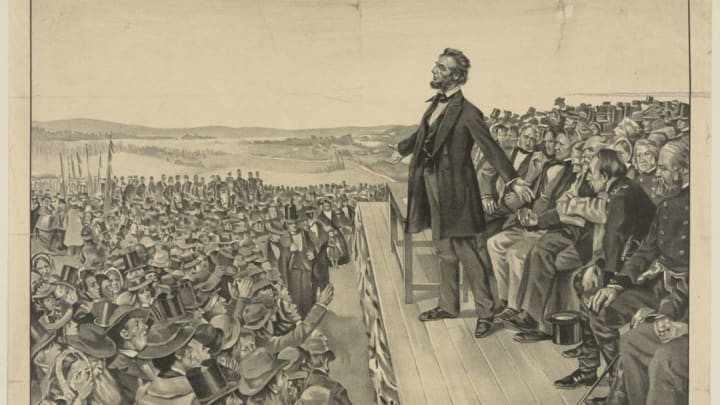

8. There’s only one confirmed photo of Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg.

In 1952, archivist Josephine Cobb was studying a glass negative of a photo taken by David Bachrach when she spotted a familiar face in the crowd at the Gettysburg dedication ceremony. It was Abraham Lincoln, his hat-less head slightly bowed as he waited for his turn at the podium later that afternoon. Alexander Gardner also snapped a photograph at the occasion that might show Lincoln, too, but people disagree about exactly where Lincoln appears. John Richter, director of the Center for Civil War Photography, identifies him on horseback, while former Disney animator Christopher Oakley places him on the ground several yards to the right.