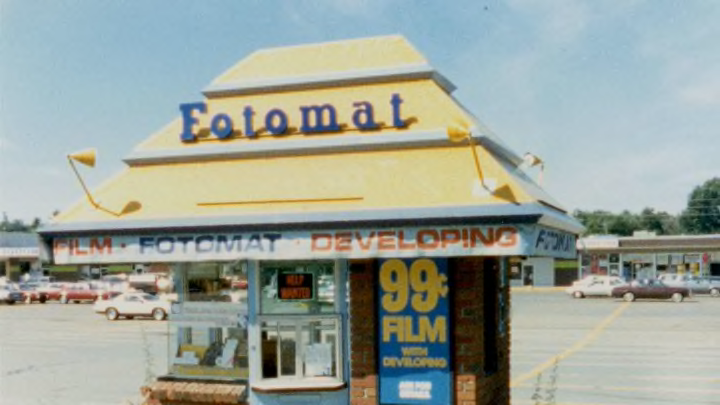

Like the Golden Arches of McDonald’s that came before it, the familiar gold and pyramid-shaped roofs of Fotomat locations acted as a beacon. Instead of hamburgers, Fotomat was in the photography business, offering tiny huts situated in shopping plaza parking lots that were staffed by just one employee. Men were dubbed Fotomacs. Women were known as Fotomates, and management required them to wear short-shorts, or “hot pants,” in a nod to the strategy used for flight attendants at Pacific Southwest Airlines.

Cars pulled up to the Fotomat location and dropped off film they wanted processed. After being shuttled via courier to a local photo lab, it would be ready for pick-up the following day. And aside from selling film and a foray into renting videocassette tapes, this was all Fotomat did.

The idea, which was originally made popular by wealthy aviator Preston Fleet, was almost deceptively simple in concept and execution. At the height of Fotomat’s success in the 1970s and early 1980s, there were more than 4000 of the tiny kiosks located across the United States and Canada. But even with extremely low overhead—the little huts didn’t even have bathrooms—and a widespread love of photography, Fotomat fell victim to its own success. Its legacy even grew to include a former company president who became a federal fugitive from justice.

In the 1960s, Americans were fond of Kodak Instamatic cameras and film. People submitted the familiar yellow spools full of images from weddings, birthdays, trips, and other social events to photo processing labs, which might take days to return prints.

That’s where Preston Fleet saw opportunity. Fleet was a wealthy aviation enthusiast. His father, Reuben Fleet, had founded the Consolidated Aircraft Company—later known as Convair—which manufactured aircraft for World War II. Born in Buffalo, New York, Fleet moved with his family when the airplane business was relocated to San Diego. On the West Coast, he met Clifford Graham, an entrepreneur well-known in La Jolla, California, for his multiple business pursuits. Graham also had a reputation for carrying a gun and leading investors astray with questionable business practices.

Fotomat, however, was no hustle. The concept of a kiosk where people could easily drop off and pick up film that would be ready overnight originated in Florida, where Charles Brown opened the first location in 1965. After buying Brown's stock shares and arranging for a royalty, Fleet and Graham founded the Fotomat Corporation in 1967, with Graham president and Fleet vice-president. The concept grew quickly, boasting 1800 sites in its first 18 months of operation. Owing to its color scheme, people often thought Kodak operated the business, which led to complaints from Kodak as well as lawsuits. (Fotomat changed its design in 1970 to avoid confusion.)

While it was relatively easy to slot in a Fotomat hut in a parking lot, a business operating as an island surrounded by traffic had its problems. Remembering an old Fotomat in New Dorp on Staten Island, residents on Facebook recalled plowing into the kiosk or backing into it. (Most notably, terrorists destroy a Fotomat lookalike hut in the Twin Pines Mall lot in 1985’s Back to the Future.)

There was also the matter of bathrooms: They weren’t any. Employees often made arrangements to duck into local supermarkets or other stores when nature demanded it.

Hot pants and a lack of lavatories aside, Fotomat performed so well that Fleet and Graham decided to take it public in 1969, with each man holding stock worth $60 million at one point. But Graham’s controversial business practices made him a short-timer. In 1971, he was ousted from Fotomat over allegations he was misusing funds for his own personal gain, including his political interests—Graham was a supporter of both Richard Nixon and football player-turned-congressman Jack Kemp, who became an assistant to the president in the Fotomat corporation and referred football pros to become franchisees.

By the early 1980s, Fotomat—now minus Fleet, who had sold off his shares, and Graham—had opened over 4000 locations. That was both impressive and problematic. Fotomat had far overextended itself, sometimes opening kiosks so close to one another it cannibalized sales. There was also a growing number of pharmacies and grocery stores offering photo development services.

The real death blow for Fotomat, however, wasn’t over-expansion. It was the emergence of the one-hour minilab.

For an investment of $50,000 to $100,000, existing stores could install labs that could process photos in as little as one hour while customers shopped. Minilabs exploded from just 600 locations in 1980 to 14,700 by 1988. And since film never left the sites, it was less likely to get lost. It decimated Fotomat and its copycat businesses, with Fotomat moving from an impressive 18 percent market share in the photo processing industry to just 2 percent by 1988.

The company tried to recalibrate, converting home movies to videotape and even offering VHS rental during the VCR boom of the 1980s, but it wasn’t successful. Mass layoffs and closures followed. (Minilabs would have their own reckoning, both due to the rise of 35mm photography and digital photography.) In 1990, Fotomat was down to just 800 locations.

Fleet, who had exited Fotomat years prior—the company had been sold to Konica—was no worse for the wear. Prior to his death in 1995, he authored a book, Hue and Cry, which called into question the authenticity of works attributed to William Shakespeare. He was a founding director of the San Diego Aerospace Museum in 1963. He also helped popularize Omnimax, an immersive theater experience owned by Imax, installing a screen at the Reuben H. Fleet Space Theater and Space Museum in San Diego in 1973.

Graham’s future after Fotomat was far more colorful. Promoting a bogus gold mining operation he named Au Magnetics, he promised he could turn sand into gold. Instead, he was accused of fleecing investors. When a federal grand jury handed down an indictment that included charges of mail fraud, wire fraud, and tax evasion in 1986, Graham was nowhere to be found. Nor would he ever be located. Associates speculate he either successfully eluded authorities or was possibly killed by an investor who was unhappy with losing money.

As for the Fotomat locations themselves: Following the company’s collapse, many were repurposed into other businesses. Some became coffee shops; others morphed into watch repair kiosks, locksmith huts, windshield wiper dealers, or tailors. Presumably, none of the owners who took over mandated their employees wear hot pants.