Iron filings don’t seem like obvious playthings. They’re extremely unpleasant if swallowed, can cause great harm to the eyes, and are best not inhaled. Yet they are at the core of one of the world’s best-loved toys: Wooly Willy.

Back in good ol’ 1955, the width of the country away from where Marty McFly was reuniting his parents, an icon was born. Smethport, Pennsylvania, had a few claims to fame already—it was home to America’s first dedicated Christmas store and also held the dubious honor of being Pennsylvania’s coldest town. But a cheerful, hairless, two-dimensional man was about to change that.

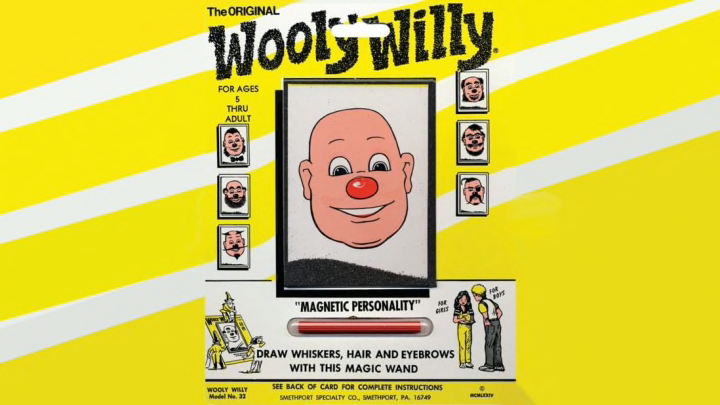

James Reese Herzog—himself a three-dimensional man with a fine head of hair—was working in his father’s toy factory, the Smethport Specialty Company, where they mainly produced spinning tops and magnet sets. "The ends of the magnet had to be run across a grinding wheel to make them level and it created a lot of dust. I came in and ground the magnets one day and all of a sudden it came to me," Herzog later wrote in American Profile of the genesis of his idea for Wooly Willy, a classic toy that lets kids wield a tiny wand to create a variety of hairstyles on an otherwise bald cartoon face. "I put a pile of dust on a piece of cardboard and used magnets to play around with it."

At around the same time, the Army was using new techniques with plastic to make three-dimensional maps. Known as vacuum-forming, the process involves a sheet of plastic being heated and then shaped around a mold. Herzog’s brother Donald learned about this and suggested it could be used to contain what would be Wooly Willy’s hair. Leonard Mackowski, an artist from nearby Bradford, Pennsylvania, was recruited to create Willy’s face, and the Herzogs found themselves with a brand-new product.

Sadly, even with its tiny 29-cent price tag, it was a product nobody wanted. James Herzog recalled one retailer describing Wooly Willy as the worst toy he had ever seen. Eventually one store owner placed an order for 72 of them, partly to prove a point that they would never sell and encourage the Herzogs to move on from what he saw as manifestly a terrible idea. Two days later he called back and ordered 12,000. Wooly Willy was a phenomenon.

Over the years, Wooly Willy has spawned countless imitators. Some, like Dapper Dan the Magnetic Man, were produced by the Smethport Specialty Company. But many more were simply "inspired" by Wooly Willy.

As Herzog said, the packaging was the product, which made manufacture extremely inexpensive. So along came Mr Doodleface and Hair-Do Harriet, Baby Face and Hairless Hugo, as well as the horror-inspired Thurston Blood, Eaton Brains, I. Sockets, and Ben Toomd. There have been official Simpsons versions, not-particularly-official-looking Beatles versions, and mentions everywhere from Family Guy to That ‘70s Show. Wooly Willy is everywhere, from this incredibly impressive real-life homage to this all-Bill Murray tribute. He’s been named as one of the 100 most influential toys of the 20th century by the Toy Industry Association.

The original, official version, complete with Smethport name-drop (and artist Mackowski’s signature hidden in the artwork), has sold a staggering 75 million units in the 65 years since its creation. That’s more than 1 million a year—an incredibly difficult figure to sustain for that long, especially for a product that has changed so little, hasn’t lent itself to multimedia spinoffs, and isn’t what you might call high-tech.

It’s been a dollar-bin staple, filled countless party bags, and made umpteen long car rides go by faster. Herzog attributes Wooly Willy's success to its simplicity: You don’t need to put hours of effort in, or have any artistic flair whatsoever, to get fun results. It’s a happy-looking man with silly hair, and that’s it.