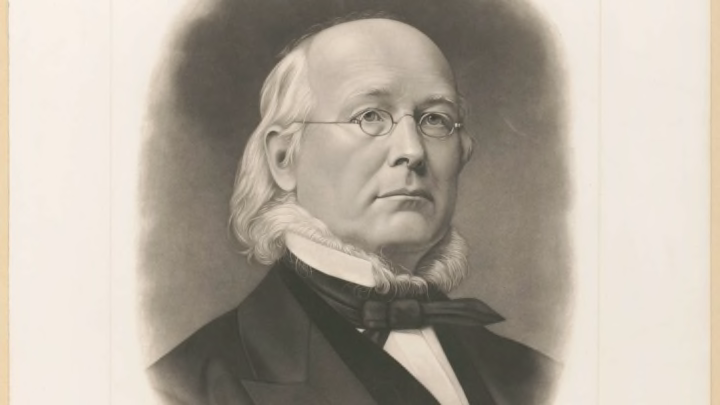

In the mid-19th century, the Whig Party played host to several eminent politicians of the era, including founder Henry Clay and Presidents William Henry Harrison and Zachary Taylor (both of whom died in office). Also a member was Horace Greeley, one of the most influential and well-respected newspaper editors in American history.

After founding the New York Tribune in 1841, Greeley quickly made a name for himself as a principled editor who printed everything from Karl Marx's coverage of European news to personal editorials denouncing slavery (and women’s suffrage). The newspaper became a vehicle for Greeley’s political outspokenness, which wasn’t always without backlash; in 1864, for example, he incurred criticism for opposing Abraham Lincoln's reelection.

Though initially devoted to the Whigs, Greeley showed a willingness to test out—and even help form—new parties that more closely aligned with his own values. When the Whigs failed to oppose slavery as strongly as he did, he threw his support behind the up-and-coming Republicans; and he defected from that party to establish the Liberal Republican Party after Republican Ulysses S. Grant peppered his first presidential term with corruption.

An Ill-Fated Pivot to Politics

It seems that a man so entrenched in politics might harbor hopes of running for office himself, and Greeley definitely did. When Grant ran for reelection in 1872, Greeley tossed his hat in the ring as the Liberal Republican nominee. His high profile as a media heavyweight helped him win the nomination; and the Democratic Party, thinking unity was their best chance at defeating Grant, even chose to support him instead of their own potential candidates.

Campaign season was much less smooth. Greeley had advocated for the pardon of Confederate president Jefferson Davis after the Civil War, and Northerners skewered him for being too soft on the South. Stoking the fire were the political cartoons of Thomas Nast and other artists, who depicted Greeley as a self-serving philosopher willing to do anything to beat Grant—even forging alliances with groups like the Ku Klux Klan. “I have been assailed so bitterly that I hardly knew whether I was running for the presidency or the penitentiary,” Greeley reportedly remarked.

By autumn, he was utterly depleted, a state made worse by the rapid deterioration of his wife’s health. Days before the election, she died from “a severe attack of lung disease,” according to her obituary in The New York Times. The election results exacerbated his anguish. Though Greeley performed respectably in the popular vote—earning about 2.8 million to Grant’s 3.6 million votes—he was only projected to win 66 electoral votes, while Grant would amass 286.

Tragic Demise and Electoral Confusion

Then, on November 29, before the electoral college had actually cast any ballots, Greeley himself died. We don’t know exactly what caused his death, but his behavior in the weeks after Election Day offers some insight. Not only was Greeley reeling from the death of his wife and his imminent political defeat, he was also mourning the loss of the New York Tribune, which had just decided to sever ties with its founder. In a missive penned on November 13, Greeley laid bare his hopelessness.

“ … having done wrong to millions while intending only good to hundreds, I pray God that He may quickly take me from a world where all I have done seemed to have turned to evil,” he wrote, “and wherein each hour has long been and henceforth must be one of agony, remorse, and shame.”

On November 19, the 61-year-old editor retreated to Dr. George Choate’s sanatorium near Tarrytown, New York, to recover from a nervous breakdown. “Since his arrival at Tarrytown, Mr. Greeley had evinced great mental disquietude on the subject of his worldly affairs, and the impression grew upon him to such an extent that he became gloomy and despondent, and refused to take more than a small portion of nourishing food at long intervals,” his New York Times obituary read. It’s also possible, as ProPublica’s Scott Klein writes for Medium, that doctors’ limited understanding of psychiatry resulted in drug treatments that worsened Greeley’s condition—or even proved fatal.

In any case, Greeley’s sudden death left members of the electoral college wondering what to do with his electoral votes. Instead of casting their ballots for a now-deceased candidate (which, strangely, has happened in several smaller elections), most decided to vote for a different candidate who, though alive, still had no chance of winning. Greeley’s running mate, Benjamin Brown, received 18 votes; 42 votes went to Thomas Hendricks, Grover Cleveland’s future vice president; two Georgia representatives voted for Georgian Charles Jenkins; and David Davis, who had competed against Greeley for the Liberal Republican nomination, received one vote. Three electors did follow through on their pledge to vote for Greeley, but their ballots were voided.

It’s the only time that a presidential candidate has died before the electoral college voted, but that’s not to say it couldn’t happen again. Though the voting process has become more efficient in the last 150 years, there’s still a sizable gap between Election Day and the day electors vote, which is always set for the Monday after the second Wednesday in December—this year, that’s December 14.

[h/t Medium]