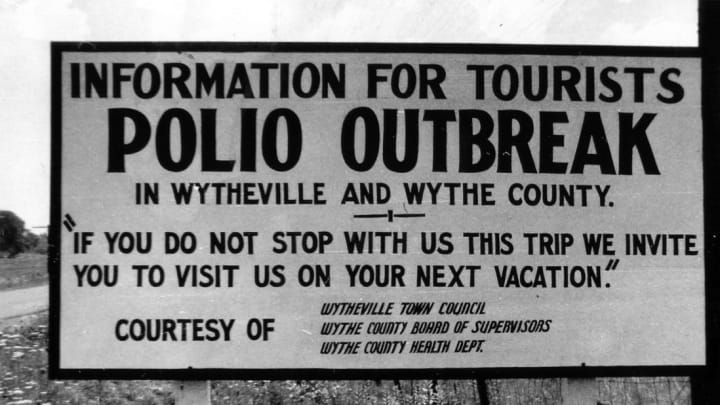

In the summer of 1950, the southwest Virginia community of Wytheville became a ghost town. Movie theaters, public schools, and churches shut their doors. Signs were placed along roads warning travelers to avoid stopping or risk infection. A polio epidemic was sweeping through.

The infection, formally named poliomyelitis because it attacks the protective sheaths (or myelin) surrounding nerve fibers, is caused by the poliovirus. It is most commonly transmitted through water or food contaminated with human waste, especially in public areas like swimming pools and amusement parks, and from person to person through contact with contaminated objects or respiratory droplets. Symptoms include headaches, fever, nausea, fatigue, and stiff necks. But serious cases, while rarer, can lead to meningitis, paralysis, or death. And until 1955, there was no vaccine.

This was bad news for the small Virginia town. In trying to slow the polio outbreak, Wytheville's resources would be stretched thin. And by the end of the summer, there would be over 200 infected out of a population of 5000—making it the most concentrated outbreak of polio in U.S. history.

A Presidential Case of Polio

The first recorded polio epidemic in the United States occurred in Vermont in 1894. According to David M. Oshinsky, author of Polio: An American Story, there were 123 total cases, including 50 severe cases and 18 deaths. Most of the patients were male; 68 percent of all patients were under 6 years old. The same demographics were seen among the thousands of cases during the New York City polio outbreak of 1916.

But the disease wasn’t well known until the diagnosis of future U.S. president Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1921. His condition began with gradual weakness, numbness in his legs, and a fever, and progressed to paralysis. Roosevelt spent much of his four presidential terms in Warm Springs, Georgia, receiving water therapy to regain strength in his legs. He became the public face of the disease, showing that anyone—not just children—could be infected.

In 1938, Roosevelt founded the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, now known as the March of Dimes, and raised funds to support polio research and a cure. Families across the nation sent in what amount they could spare, hoping their children wouldn’t be among those directly affected. The organization funded scientists like Jonas Salk to develop a vaccine, but it wouldn’t come about until years later.

Despite the publicity and research, polio still ravaged communities every summer. In 1950, that community was Wytheville.

“Polio Season” in Wytheville

The summer baseball season began and crowds came out to see the Wytheville Statesmen take on the Wilkesboro, North Carolina, Flashers. Tourists started to trickle in from the north for their vacations when “polio season” began, as it had around the country year after year.

“Polio seasons were unpredictable,” Oshinsky writes in Polio: An American Story. “Some began in late May and burned out by mid-August. Others came in July and lasted through Labor Day.”

That was the case in Wytheville when, in late June, the first case of the year was confirmed. It was Johnny Seccafico, the toddler son of one of the team’s players. The community raised money for Seccafico’s care in a children's hospital.

Another one of the infected was James “Sonny” Crockett, son of the baseball team’s manager. His sister Anne Crockett-Stark has become an unofficial spokesperson for the Wytheville polio epidemic because there are few people who still remember it.

“We were told to stay downstairs, my older sister, me, and my little brother,” Crockett-Stark tells Mental Floss, remembering the day her brother was diagnosed with polio. “They went upstairs and evidently did a spinal tap on my brother and it must have been very painful [because] they held him down.”

The spinal tap was the only real way to diagnose polio. Once confirmed, Crockett-Stark watched the doctors take her brother away in a hearse. She assumed he had died, but they used the vehicle only to transport him to the hospital, because there were too few ambulances to serve the small town.

Keep Out

Town officials imposed a quarantine that kept families indoors and included signs telling travelers to stay out. Residents kept their windows tightly shut in their cars and houses, despite both lacking air conditioning to combat the Southern humidity. The streets emptied, playgrounds were abandoned, and school books remained closed. It prompted people to call the polio season of 1950 the "summer without children."

People didn’t know how to prevent infection, and they followed the advice of old wives’ tales—holding handkerchiefs in front of their faces, wearing garlic around their necks, and bathing in bleach. To avoid stores, families ate from backyard gardens or arranged to have their groceries delivered.

Parents were also tasked with entertaining their children indoors for months. School was canceled and lessons were given over the radio. Parents burned their children's belongings to destroy any possibility of the virus spreading.

Sonny Crockett’s toys and furniture were taken away as a precaution. “They took his bed, his mattress, his chest, all his clothes, his Erector set, Lincoln logs, his comic book collection, everything,” Crockett-Smith says. “We lived in an old Victorian home built in 1900 and daddy closed off part of the front porch and built a room and put the cot in there.”

An Epidemic of Rumors

Word passed around the community about potential causes of the outbreak. A local newspaper tried to alleviate fears by publishing hopeful stories and focusing on facts from the experts rather than letting misinformation run rampant. A chalkboard on the paper's wall tracked new cases and deaths.

“I think just like today [with coronavirus], nobody exactly knew what caused it. And what was happening," Crockett-Stark says. "There were a lot of individuals and groups that thought this or thought that. And so there were a lot of different truths.”

The local hospitals weren’t prepared for the surge in cases, and many victims had to drive 80 miles to Memorial and Crippled Children’s Hospital in Roanoke, Virginia. The doctors and nurses who treated polio patients were often overworked and caught the virus themselves.

While all groups of people could be infected, not all were given the same treatment. Black patients were denied admission at the then-segregated Roanoke hospital. Instead, they had to drive almost 300 miles of country roads to Richmond, long before the creation of the more direct interstate.

Many patients were treated with an iron lung, a metal box that served as a ventilator from the patient’s neck down. It uses air pressure to make the person’s chest expand and contract. A Wytheville man claimed the Guinness World Record for spending 42 years in one.

Like in Sonny Crockett’s case, funeral homes lent out hearses to act as makeshift ambulances. One even purchased an iron lung to use during transport. A local shoe maker began making leg braces for children with post-polio syndrome, a condition that can sometimes follow the virus, leading to muscle and joint weakness.

Wytheville After the Epidemic

Staff and supplies arrived to combat the epidemic, including $32,000 from the March of Dimes. Then, as quickly as the virus appeared, it left. By September, health authorities claimed that polio was all but gone, with cases becoming fewer and milder. The person-to-person contact that led to the high transmissions in the summer became less common as temperatures cooled. Between 10 and 20 Wytheville residents had died from the disease, according to differing state and local estimates.

Much of the town reopened and the schools welcomed students in October. Jonas Salk's polio vaccine was distributed in 1955, and a few years later, a massive national vaccination campaign took place using a safer vaccine. By the next decade, mass vaccination had cut polio cases in half.

Seccafico and Crockett both survived polio but had lingering effects of the disease. Crockett-Stark still lives in Wytheville. The town's Thomas J. Boyd Museum has an iron lung on display, along with oral histories from the people affected by the epidemic, as a reminder of that terrifying summer.