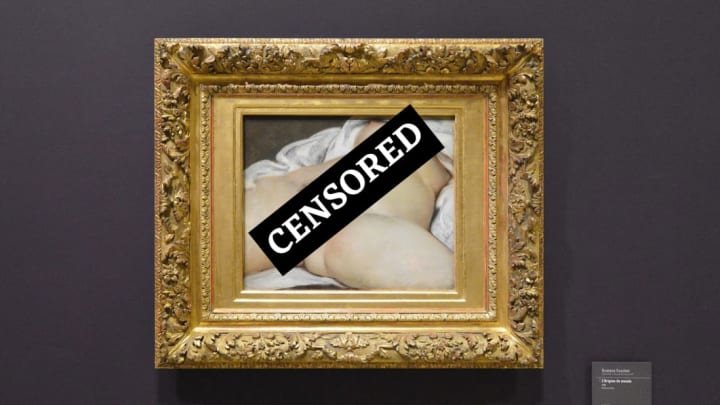

Visitors to the Musée d'Orsay in Paris often encounter a startling sight. While browsing the section of the gallery devoted to the works of French Realist artist Gustave Courbet, they'll come across an unusually graphic 1886 painting entitled L’Origine du monde (The Origin of the World). It's famous for its portrayal of a woman reclining naked, her exposed genitals at the center of the image. While life drawing and painting have long been a part of the history of art, it was unusual at the time to portray a vulva in such an explicit way.

Courbet’s choice to show the woman's unclothed body without including her head or face was also unconventional. The lack of the latter meant that identifying the model who posed for the painting became an unusually difficult task—and the source of much speculation.

An Art History Mystery

It was long thought that the subject of L’Origine du monde was most likely Joanna Hiffernan. Hiffernan was a popular model of the period—she posed for four of Courbet's other paintings—and an artist in her own right. She was, however, a redhead, as showcased in Courbet’s painting Jo, La Belle Irlandaise. The woman in L’Origine du monde, meanwhile, has dark body hair, which was not the shade that would be expected of a natural redhead.

As the years passed, the model's identity remained a mystery. The fact that her head wasn't pictured wasn't the only challenge in revealing her identity; the artwork's explicit nature meant it was considered too scandalous for public display—in fact, it was exhibited on just a handful of occasions—so people couldn't analyze it for potentially identifying details. Even those who kept it in their private collections often concealed the artwork.

Reproductions of the painting also caused controversy. In 1994, the French police demanded that bookstores in Clermont-Ferrand and Besancon remove a book that used the image of the painting on the cover from their window displays.

The Musée d’Orsay decided to brave any potential controversy and finally put the painting on permanent public display in 1995. The debate over whose body was being portrayed in the painting would continue for a number of years—until a breakthrough finally came 23 years later.

The Model Revealed

In 2018, a French historian named Claude Schopp announced he had uncovered documentary evidence that identified the painting’s mysterious model: Constance Quéniaux.

Quéniaux was a successful dancer and courtesan in the Paris Opera Ballet during the mid-19th century. Admirers of her work included the writer Théophile Gautier, and she was regarded highly enough to be photographed in costume by the renowned photographer André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri. She was also linked to Khali Bey, the Ottoman ambassador of France at the time—and the man who commissioned the painting.

While consulting correspondence between the writer George Sand and Alexandre Dumas, Schopp discovered that Dumas had referred to Courbet’s painting in one of his letters. He expressed his disdain that the artist has painted “Ms. Queniault of the Opera, for the Turk who took refuge inside it from time to time.” He quickly realized Queniault was a misspelling of Quéniaux. After consulting the original manuscript of the letter, he also noticed that Dumas underlined the word interior to signify it was a play on words (“interior” being an allusion to the intimate angle of the subject’s body). Meanwhile, “The Turk” was a reference to Bey.

Bhey commissioned the erotic painting after he moved to Paris in the early 1860s. He kept the intimate image concealed behind a green curtain, revealing it only to certain visitors—but when his lavish lifestyle left him in financial ruin, his collection of artwork, including L'Origine du monde, was sold in 1868 to pay his debts.

For years, L’Origine du monde shuffled among various private collections. The psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan purchased the painting in 1955 and kept it at his private residence. He commissioned a screen by his brother-in-law Andre Masson, which portrayed a more stylized outline of the subject, to cover the painting when guests who might be offended were in the house. After Lacan’s death, his family donated the painting to the French state in lieu of tax, which is how it came to be publicly displayed at the Musée d’Orsay.

Quéniaux, meanwhile, went on to live a life of luxury. When she died in 1908, she left a painting by Courbet in her will. The artwork featured open camellias—a floral symbol then associated with courtesans.