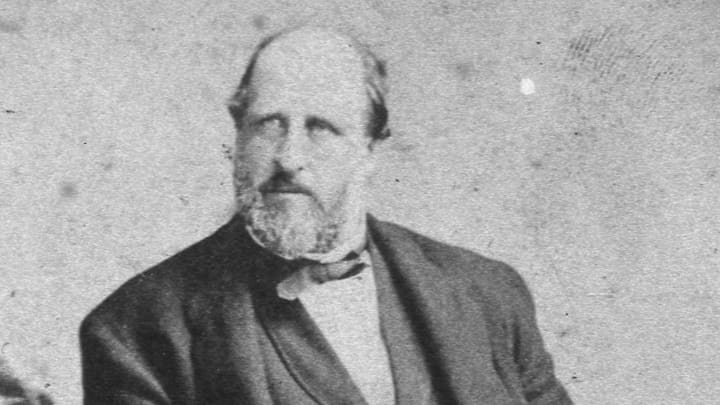

Few men are as synonymous with political corruption as William Magear Tweed—“Boss Tweed,” as most knew him. The “Grand Sachem” of New York City’s Democratic political machine, Tammany Hall, effectively ran Gotham during the late 1860s and early 1870s, treating its coffers as his personal bank account and its leaders as his errand boys. But his decadent ambitions earned him plenty of enemies, and eventually proved his undoing. Here are a few facts about the Boss and some of his more egregious activities.

1. Boss Tweed learned politics while working as a fireman.

Tweed was initially groomed to go into his father’s business as a chair-maker, before going to school for accounting (learning skills that no doubt proved helpful when he was cooking the city budget). But he found his true calling upon joining the volunteer fire company, where he would help form Americus Engine Company No. 6. It was in this world that he learned how to develop alliances and work the system, developing strong-arm tactics to ensure that his engine was the first that made it to a fire.

His competitiveness and hostility toward other firehouses in the city almost got him expelled from the firefighters—but his penalty was reduced to a three-month suspension. All of these skills, and the working-class associates he made, helped stoke his interest in politics. It’s appropriate that Engine 6's snarling tiger logo would become the symbol of Tammany.

2. He may have saved a Republican mayor's life.

One of Tweed's earliest political moves was to help protect the life of a mayor from a different party. During the Draft Riots of 1863, while Tweed was deputy street commissioner, many of the city’s poor and Irish residents (Tammany’s core constituency) took to the streets in violent protest against the conscription law that required they pay $300 or serve on the battlefield for the Union during the Civil War. Tweed took on the role of peacemaker, urging calm, and was one of those who informed Republican mayor George Opdyke that City Hall was not safe, convincing him to go somewhere he could avoid the anti-draft violence.

Never one to miss an opportunity, Tweed leveraged the goodwill he earned for tamping down the riots into a deal that allowed many of the poor to avoid the draft, and paid the $300 conscription exemption cost for others—earning him a major political victory over the Republicans.

3. He stole big.

Tweed and his cronies stole somewhere between $30 million and $200 million from the city ($614 million to more than $4 billion in 2020 dollars) while in control of New York's political machine. During his glory days, Tweed was the third-largest landowner in New York City, with a mansion on Fifth Avenue and 43rd Street (with a horse stable nearby), a Greenwich estate, and two yachts.

4. He held a lot of positions ...

While he is most famous for his position as Grand Sachem (or “Boss”) of Tammany Hall, Tweed used his influence and skill with handing out political favors to land a wide range of titles. He served terms in the U.S. House of Representatives and the New York State Senate, and had himself appointed deputy street commissioner of New York City. He served as director of the Erie Railroad, proprietor of the Metropolitan Hotel, and director of the Tenth National Bank. He bought the New-York Printing Company and Manufacturing Stationers’ Company, then saw that they were made the city’s official printer and stationery printer, respectively (and that they overcharged for their services).

5. ... and even faked being a lawyer.

Despite never studying as an attorney, Tweed was certified as a lawyer by his friend George Barnard. Opening a law office, he was then able to charge exorbitant fees to individuals and companies seeking his influence, under the catchall phrase “legal services.”

6. Boss Tweed's allies tried to erect a statue of him—while he was still alive.

In 1871, Tammany pushed to build a bronze statue in Manhattan in Tweed’s honor (though the project was originally suggested as a spoof by journalists). While this may have seemed perfectly reasonable to Tweed, the press was not so enthusiastic. “Has Tweed gone mad, that he thus challenges public attention to his life and acts?” the Evening Post wrote. Sensing that a statue might be a step too far, Tweed suggested to those behind the campaign: “Statues are not erected to living men … I claim to be a live man, and hope (Divine Providence permitting) to survive in all my vigor, politically and physically, for some years to come.” The plans were scrapped.

7. He shared the wealth.

One of Tweed’s greatest skills was getting the men he selected into positions of power. From running the Tammany Hall general committee (which controlled the Democratic Party’s nominations for all city positions) early in his political career, to seeing that former New York City mayor and Tweed protégé John T. Hoffman ascended to the state governorship, Tweed made sure that power and profits were distributed widely among his friends.

But while his favors almost always served his own selfish purposes, they could also help the city’s people—if at the expense of the city itself. “It was assumed by most others, including those who benefited most, that his generosity was all about votes. As it was. But one thing was certain: Because of Tweed, New York got better, even for the poor,” author and journalist Pete Hamill wrote in 2005.

8. Tweed was a man of excess—but didn't smoke.

Tweed’s most famous accessory may be the huge 10.5-carat diamond stickpin he wore on his shirt front. The gifts one of his daughters received on her wedding day were reported to be worth $14 million in today’s money. He also feasted on duck, oysters, and tenderloin at the famous Delmonico's restaurant, and his significant waistline certainly didn't hide his love of excess. Despite his numerous other vices, Tweed didn’t smoke and barely drank—though he kept plenty of cigars and whisky on hand for any visiting friends.

9. Cartoons ultimately took him down.

Tweed made plenty of enemies, but perhaps his toughest was Harper’s Weekly political cartoonist Thomas Nast. The German immigrant vividly conveyed the city’s corruption with images of a bloated Tweed, replacing his head with a bag of money in one famous depiction, and using the snarling visual of a tiger (from Tweed’s own Engine No. 6 mascot) to represent the predatory Tammany Hall.

Tweed recognized the power and danger that Nast’s widely seen illustrations presented: "My constituents don't know how to read, but they can't help seeing them damned pictures!" As he did with so many others, Tweed attempted to pay for Nast’s acquiescence, sending a crony (pretending to a representative for a European benefactor interested in studying art) to the illustrator’s house with a promise of $500,000—if he would just move to Europe for the foreseeable future. But Nast refused to be bribed, and the attempt only fueled his critical cartoons, which inflamed public outrage about Tweed's acts.

10. An arrest couldn't stop Tweed from getting elected ...

In 1871, following a devastating series of articles in The New York Times about the corruption in city government, sheriff (and Tammany man) Matthew Brennan placed Tweed under arrest, just a week before voters went to the polls to decide the Boss’s state Senate seat. Brennan accepted a $1 million bond for Tweed’s bail and moved on, and the Grand Sachem defeated his rival days later.

11. ... but three more arrests got him locked up for good.

In 1873, reform lawyer Samuel J. Tilden convicted Tweed on charges of larceny and forgery, though he was released two years later. He was quickly re-arrested on civil charges, convicted, and imprisoned again (since he could not pay the $6.3 million he was judged to owe for his crimes). But life in jail did not suit Tweed, and during one of the home visits he was granted by authorities, he escaped to Cuba, then Spain, working as a seaman for two years before he was spotted by an American who recognized him from Nast's cartoons. He was captured and sent back to the U.S.

12. He eventually confessed to many of his crimes while hoping to get out of prison.

Desperate to get out of prison after his third apprehension, Tweed struck a deal with the state attorney general to confess much of what he had done, if it would mean release. He revealed all of his crimes (or at least as many as he could remember) in 1877, only to have the lawman back out of his agreement (the attorney general did, after all, work for New York’s governor and Tweed’s old foe Samuel Tilden).

13. Boss Tweed died in prison the following year.

While in prison, Tweed contracted severe pneumonia and died in 1878, reportedly worth not much more than a few thousand dollars. It was an ignoble end, and New York City Mayor Smith Ely refused to fly the City Hall flag at half-staff. His daughter was determined to keep the funeral small, allowing only close friends and family—with much of his family not even able to make the funeral (his wife and another daughter, both invalids, lived in Paris and his two sons were in Europe).

A version of this story originally ran in 2016; it has been updated for 2022.