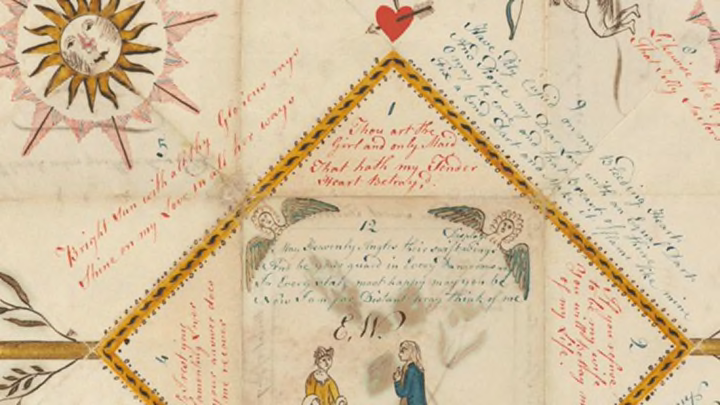

This love token, made by a heartsick young man in late 18th-century New England, folds up into a small square. Its flaps are embellished with verses and drawings. John Overholt, a curator at Harvard’s Houghton Library, which holds this particular example of a late-18th-century “puzzle purse” love token, writes that the library knows little about its origin story—only the initials of the author, E.W., and that he “apparently created this piece after the object of his affections turned down his proposal of marriage.”

According to Overholt, German immigrants to Pennsylvania started the practice of making puzzle purse love tokens; the custom then spread to New England, where E.W. lived. Historian Leigh Eric Schmidt writes that some surviving love tokens made during the late 18th and early 19th centuries refer directly to the custom of “drawing lots” to see who, of a given pool of young men or women, was likely to be the selector’s sweetheart. (One such verse read: “Lots was cast and you I drew/Kind fortune favoured me with you/Sure as the grape grows on the vine/I choos’d you for my valentine.”)

This love token was produced by a lad in somewhat greater extremity: E.W. had already expressed his affection to the recipient and been turned down. “Thou art the Girl and only Maid/That hath my tender heart betray’d,” E.W. moaned. With hope for a better outcome in the future, he wrote: “Have pity Cupid on my bleeding heart/And Pierce my Dear Love With an Equal Dart.” In the meantime, he hoped that she would be blessed with good fortune, writing on one flap embellished with a smiling sun: “Bright Sun with all thy glorious rays/Shine on my Love in all her ways.”

Houghton Library, Harvard University // Public Domain

Houghton Library, Harvard University // Public Domain

Blogger Lady Smatter, who recreates crafting customs from Jane Austen’s time period, tried to reproduce some puzzle purses in order to see how they might have been made, and reported that the experience left her impressed with the craftsmanship of the young men (and sometimes women) who made these tokens. “Puzzle purses have space for three layers of decoration: 1) the outside when fully folded, usually decorated with a large heart; 2) the ‘pinwheel’ formed when the flaps decorated with the large heart are unfolded; and 3) the central area of the sheet that’s exposed when the pinwheel is unfolded,” she wrote. “This puzzle purse [by Sarah Newlin, from the American Folk Art Museum] fills all three layers with distinctive decoration and poetry, but no part of the unfolded sheet of paper has decoration on both sides. It’s organized very carefully and cleverly.”

Perhaps this careful organization, while speaking of the crafter’s depth of feeling for the recipient, had a deeper meaning. “The very complexity of the puzzle purses—the layers, folds, and multiple scenes—suggested something of the intricacy of courtship itself, a folk expression of the convoluted social rituals of attaining intimacy,” Schmidt writes. In a time when people had to follow very particular scripts in order to retain respectability while advancing courtship, the making of a love token was an exercise in ardent patience.

Comparable examples of love tokens from the late 18th century can be seen on the websites of the American Folk Art Museum, Sotheby’s, the Free Library of Philadelphia, and the British Postal Museum.