The First World War was an unprecedented catastrophe that shaped our modern world. Erik Sass is covering the events of the war exactly 100 years after they happened. This is the 220th installment in the series.

January 17, 1916: Russians Advance on Erzurum

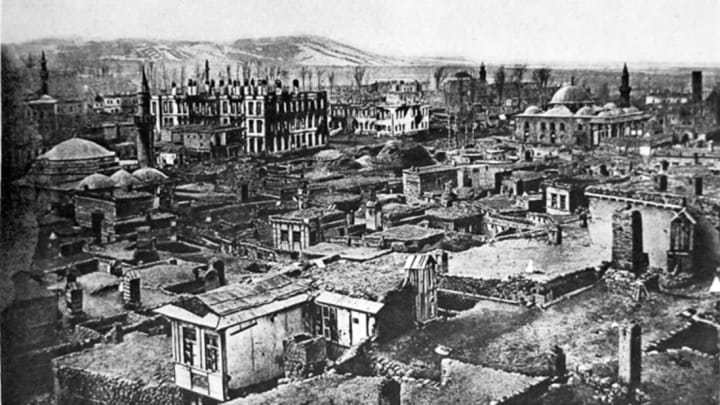

As fighting in other theatres died down during the winter months, a long period of stasis on the Caucasian front suddenly ended with a surprise attack by the Russian Caucasian Army, which sprang into action against the understrength Ottoman Third Army in Eastern Anatolia and scored a major victory at the Battle of Köprüköy from January 11-19, 1916. This set the stage for an advance on the ancient city of Erzurum (above), occupying a key strategic position at the gateway to central Anatolia, the Turkish heartland.

Click to enlarge

Following its disastrous defeat at Sarikamish, the Ottoman Third Army had withdrawn down the Aras River valley to strong defensive positions around the small village of Köprüköy, nestled between the imposing ridges of the eastern Pontic Mountains. However the Ottoman high command was unable to send reinforcements to the badly depleted Third Army, as all available manpower was needed to fight off the Allied attack at Gallipoli; thus the Third Army lacked the defensive reserves needed to plug the gaps in case of an enemy breakthrough.

With the approval of theatre commander Grand Duke Nicholas, who had been relieved as commander in chief of all the Russian armies and sent to the Caucasus in August 1915, the Russian commander General Yudenich staged a flurry of diversionary attacks on January 11 before unleashing the main assault on a weak spot in the Turkish line near the Cakir-Baba ridge on January 14. The diversionary attacks succeeded in distracting the Turks, who moved their only reserve away from the intended area for the main attack; the Russians rebuffed a counterattack by these forces on January 13.

Beginning before dawn on January 14, the Russian soldiers waded through snow higher than their waists along the southern slope of Cakir-Baba, regrouped, and seized the strategic Kozincan heights by the following day, leaving almost nothing between them and the village of Köprüköy on the Aras River. With a breakthrough tantalizingly close, Yudenich threw his Cossack reserve into the fight in hopes they could slog through the snow and surround the enemy – but the Turks withdrew just in time, retreating to the fortifications of Erzurum by January 17.

Overall the Ottoman Third Army suffered 20,000 casualties out of a total 65,000 men, while the Russian Caucasian Army lost just 12,000 out of 75,000. More importantly, the first great prize of the campaign in East Anatolia, Erzurum, was within reach.

A British war correspondent, Philips Price, recorded the aftermath of the battle and the Turks’ hasty retreat to Erzurum: “We saw many signs of the Turkish retreat, as we continued our way. Through the snow on the roadside protruded a number of objects, camels’ humps, horses’ legs, buffaloes’ horns, and men’s faces, with fezzes and little black beards, smiling at us the smile of death, their countenances frozen as hard as the snow around them.”

Meanwhile both sides had to continue enduring harsh winter conditions in the incredibly primitive environment of the eastern Anatolian mountains, which the Russian Cossacks were especially well suited for, according to Price:

Snug little zemliankas, dug into the earth and covered with grass, dotted the plateau and the sheltered hillsides. From the holes, that served as doorways, hairy Cossack faces looked out on wintry scenes of snow and rock. Here the reserves were waiting to be ordered up to the front. Mankind in this country becomes a troglodyte in winter… so they build themselves huts, half buried in the ground and covered with straw, where they can keep warm and rest for a few days… A deathly silence reigns over the white expanse of snow; and only the wolfish bark of a miserable pariah dog tells one there is any life at all.

Suffering Behind the Lines

The Russian advance in Anatolia could only serve to heighten the Ottoman government’s paranoia about Armenian subversion behind the lines, reinforcing their commitment to carrying out their genocidal policy of massacres and death marches against the Armenian civilian population.

The Armenian Genocide was no secret, openly discussed by the Ottoman Empire’s own allies. For example on January 11, 1916 Karl Liebknecht, a socialist member of the German Reichstag, asked a question addressed to the government:

Is the Imperial Chancellor aware of the fact that during the present war hundreds of thousands of Armenians in the allied Turkish empire have been expelled and massacred? What steps has the Imperial Chancellor taken with the allied Turkish government to bring about the necessary atonement, to create a humane situation for the rest of the Armenian population in Turkey, and to prevent similar atrocities from happening again?

Baron von Stumm, head of the German foreign office’s political department, responded to Liebknecht’s question with an answer that can only be described as a tour de force in euphemism:

The Imperial Chancellor is aware that some time ago the Sublime Porte, compelled by the rebellious machinations of our enemies, evacuated the Armenian population in certain parts of the Turkish empire and allocated new residential areas to them. Due to certain repercussions of these measures, an exchange of ideas is taking place between the German and the Turkish governments. Further details cannot be disclosed.

Liebknecht then returned to the attack but according to the official transcript was dismissed on grounds of parliamentary procedure: “‘Is the Imperial Chancellor aware of the fact that Professor Lepsius virtually spoke of an extermination of the Turkish Armenians…’ (The President rings his bell. – Speaker attempts to continue speaking. – Calls: Silence! Silence!) President: ‘That is a new question that I cannot permit.’” Indeed, the German government was determined to turn a blind eye to the atrocities committed by their ally.

Click to enlarge

However the record of these events survived in the testimony of the few who managed to endure the death marches, only to be dumped in a string of smaller concentration camps in the Syrian desert, where they awaited final deportation to the main concentration camps (often described as “death camps”) at Deir-ez-Zor and Rasalyn. One young Armenian girl, Dirouhi Kouymjian Highgas, later described one of the smaller camps:

As far as the eye could see were acres and acres of tents. They all looked alike. Most of the tents consisted only of two sticks pounded into the ground, with dirty, ragged blankets thrown over them. The condition of the refugees was indescribable. They were half-clothed human skeletons, either squatting in a stupor in front of their tents, or lying on the ground with their mouths open, gasping for air, or shuffling aimlessly around, staring blankly into the distance. They did not acknowledge our arrival in any way.

Here she would have the frightening experience of seeing her own father breaking in despair:

In the evenings, we sat in our tent… We tried to sleep through moans and screams of the sick and dying. We were using any available place for toilets. The human smells, the stench of rotting flesh and other undefinable odors that hung in the air were unbearable. One night, I was awakened by the sound of my father crying. He was sobbing just like a child. I reached out to him and wiped his tears away with my fingers, and curled up on my mat, to sleep… It was almost too much sadness for a little nine-year-old girl to bear. But I didn’t move. I told myself I had to be brave. I must not allow myself to break down, adding yet another problem to my already overburdened family…

While the Armenians were subjected to state-sanctioned mass murder (along with Greeks and Assyrian Christians in some places), it’s worth noting that other Anatolian populations, including Turks and Kurds, also suffered widespread starvation and disease due to the disruptions caused by the war. Henry H. Riggs, an American missionary, painted a chilling picture of the conditions for Kurdish refugees fleeing the Russian advance in eastern Anatolia:

Many of these people had actually been driven out of their village homes by the advance of the Russians, and some had fled from places where the Russians had not yet arrived rather than await the coming of the foe… The sufferings of these Kurdish exiles, however, were hardly less pitiable than those of the Armenians… The mortality among them was terrible, and those who reached the region of Harpoot were – many of them – utterly broken and hopeless… Epidemic soon took hold among them, and one of the women who had gone down to help came back one day with the report that the Kurds were dying like flies…

Similarly Ephraim Jernazian, an Armenian pastor who was protected because of his connection to foreign missionaries, later recalled the universal suffering in Urfa, in what is now southeastern Turkey:

From 1916 through 1918 Urfa was plagued with famine. Many of the local poor and refugees died of starvation. In the evening at every doorstep could be seen people looking almost like skeletons, whimpering weakly, in Turkish, “Ahj um… Ahj um…” or in Arabic, “Zhu’an… Zhu’an…” or in Armenian, “Anoti yem… Anoti yem… [I am hungry… I am hungry.]” It was unbearable. As the night wore on, silence prevailed. Early in the morning when we opened our doors, in front of every house we would see dead from starvation a Turk here, a Kurd there, an Armenian here, an Arab there.

Like Riggs, Jernazian observed that food shortages were always followed by outbreaks of epidemic disease, spreading quickly among people made even more vulnerable by starvation. Ironically this presented a respite of sorts for persecuted Armenians, as their neighbors were too sick to torment them:

During the years of famine, the deplorable conditions became worse as various diseases began to spread. The typhus epidemic especially did its destructive work. Every day, in addition to the refugees, from fifty to one hundred townspeople died of typhus alone. Urfa presented a pitiful picture. When famine and typhus began to snatch victims from all classes, it seemed that for a while harassment of the few Armenians here and there was forgotten. Starving Armenians and Turks were begging side by side in front of the same market and together were gathering grass from the fields.

See the previous installment or all entries.