Researchers at UCLA are the first to use a new, noninvasive ultrasound technique to "jump-start" the brain of a recovering coma patient from a minimally conscious state to fully conscious.

As reported in the medical journal Brain Stimulation, the 25-year-old man recently suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI) in a car accident. "The first week [after a TBI] is spent keeping the patient alive and ensuring that the brain doesn’t undergo any further damage," Martin Monti, head of the research and associate professor of psychology and neurosurgery at UCLA, tells mental_floss.

Patients who show signs of recovery usually do so within two weeks post-injury. "That’s the interesting moment, because they’re coming out [of the coma], but it’s unclear if they’re truly recovering cognitive function or not," says Monti. This is when an intervention can do the most good.

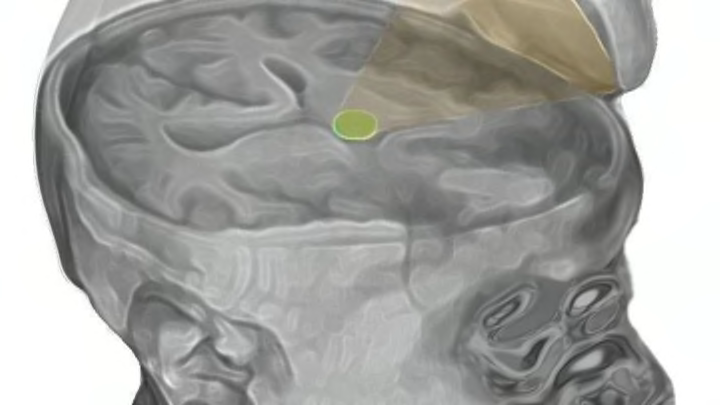

Their intervention happened to be a matter of good timing; Monti’s colleague Alexander Bystritsky, a UCLA professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences, had recently pioneered a technique called low-intensity focused ultrasound pulsation, and co-founded Brainsonix, the company that makes the device used in the trial. Traditional ultrasound "scatters a beam of sound widely," and bounces back an image (such as when looking at the image of a fetus in utero). The Brainsonix device, approximately the size of a coffee cup saucer, generates a small, focused "sphere" of energy in the form of sound waves. It can target a small area of the brain, and does not bounce back any images. Monti hoped that this targeted approach might be able to help coma patients recover more quickly.

"We are just using it to inject energy into the brain," says Monti. Specifically, he sent that energy into the region of the deep brain known as the thalamus. Composed of a pair of tiny, egg-shaped structures, the thalamus is a sort of broadcast station, Monti says. "All the information that is coming from the world to your brain goes through the thalamus," Monti says, calling it a "central hub for all information." The cortex and the thalamus "sort of talk back to each other, which is very mysterious. But we know it has to do with complex behavior—those kinds of things you can do only if you’re conscious."

At the time of treatment, their patient was showing signs of being minimally conscious. He could track movement with his eyes and occasionally attempt to reach for things, but little more. "Don't think he was conscious like you and I are," Monti says. The researchers placed the device by the side of his head, and activated it 10 times for 30 seconds each, over the course of a 10-minute period.

The day after the treatment, the patient was not only tracking and trying to reach for objects, Monti says, "he was trying to use a spoon," and could recognize objects and differentiate between them. "He also started verbalizing and would respond to things by blinking his eyes."

Three days after treatment, the patient demonstrated that he fully understood the words spoken to him, "and he clearly understood what was happening around him," Monti says. He answered questions by shaking or nodding his head. He even gave his doctor a requested fist bump.

Five days after treatment, the patient’s father reported that he was trying to walk, and at his six-month assessment, he was walking and talking. "He himself said that he felt he was 80 percent back," Monti says.

While the experiment is promising, there remains a big question. "Maybe we just serendipitously stimulated [the patient] on the day he was about to spontaneously emerge [from his coma]," Monti says. "Maybe our stimulation didn’t do anything. It’s perfectly possible that had we sang to him, the same thing would have happened." Repeated trials will be necessary to see if the ultrasound is actually what made the man’s swift recovery possible.

Moreover, Monti is unclear if this treatment can help those who are truly in a vegetative state, as coma patients tend to "recover at the beginning, and then stabilize over time," he says. Of this patient, Monti makes clear, "We didn’t switch him from unconsciousness to conscious." The patient was already minimally conscious.

Monti and his team plan to test the technique on several patients this fall at the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, in partnership with the UCLA Brain Injury Research Center. If in future trials the ultrasound technique can be used to truly awaken a coma patient who is not at all conscious, "then we’ll know it really was us," he says.

Despite these caveats, Monti allows himself to dream of future therapies derived from this technique, opening up a whole new realm of treatment for traumatic brain injuries. Right now, many brain issues require invasive surgery like deep brain stimulation. Monti thinks this form of ultrasound might be the first step toward an alternative. "Imagine this little helmet that you could put on the head of any patients [in comas] and just buzz them a little bit—without having to do any surgery. It would be amazing."