They’ve left our earthly world, but spirits sure have a lot to share with us. At least, that seems to have been the case in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a period that witnessed a boom in books said to have been drafted by the departed. That era was the golden age of Spiritualism, and many people claimed they communicated with spirits who guided their minds and hands into recording stories, poems, and even voluminous novels. Here are seven books supposedly dictated by ghosts that remain widely accessible today.

1. Historical Revelations ... (1886) // Emperor Julian and Thomas Cushman Buddington

The Roman Emperor Julian was apparently so taken aback by how civilization developed in the 1500 years following his death in 363 CE that he felt compelled to express himself from beyond the grave via the printed word. Historical Revelations of the Relation Existing Between Christianity and Paganism Since the Disintegration of the Roman Empire, recorded by American writer Thomas Cushman Buddington, attacked Christianity as the root cause of what Julian supposedly saw as a world in utter disarray and desolation. Julian’s spirit condemned Constantine and his successors for embracing “a false religion” that bred violence and stagnated Europe’s development.

More realistically, this call to return to traditional Roman values was Cushman’s rather creative way to share his own grievances. Perhaps Cushman felt uncomfortable openly lambasting Christianity as an obstacle to moral and intellectual growth and found the emperor, who studied Platonic philosophy, a suitable figure to vocalize his concerns about the human race. In his preface to Julian’s writings, Cushman praised the spirit, saying he “is of the most of the most pure and elevated character.”

2. My Tussle With the Devil, And Other Stories (1918) // O. Henry and Albert Houghton Pratt

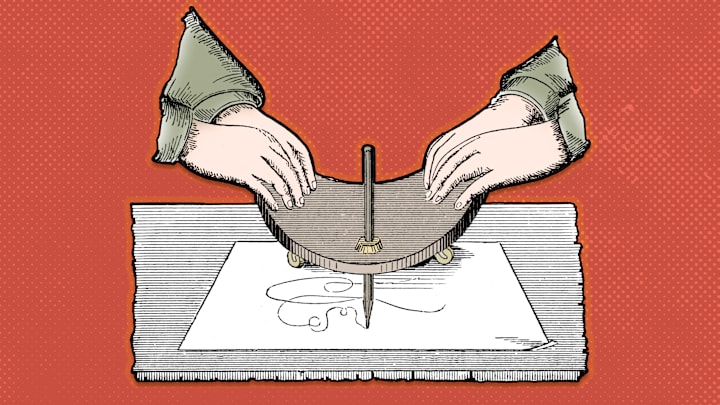

The celebrated writer known as O. Henry (born William Sydney Porter) died in 1910 with hundreds of short stories to his name. Yet even death could not halt his creative output: As eight years postmortem, a new collection of O. Henry stories surfaced, all purportedly newly written by him. They arrived through the medium Albert Houghton Pratt, who claimed that he communicated with O. Henry through a ouija board. The very first conversation had supposedly occurred on September 18, 1917, and many more followed, with Pratt inviting friends to gather around the board to listen to O. Henry’s spirit rattle off tales. Pratt, in his opening comments to the book, described O. Henry as a chatty spirit; apparently “overburdened with plots,” the ghost at times even exhausted his human companions as sessions stretched into late hours of the night. He would also self-edit his narrations: Once, he told Pratt to erase the last half of a story that had come to him too quickly and that fell short of his standards.

Pratt apparently had full control over his own thoughts throughout these sittings and found opportunities to pose his own questions. Once, he asked O. Henry what he thought about movie adaptations of his books. The spirit’s response: “Foolish rehash of yesterday’s ignorance.”

It appears Pratt anticipated the negative reception of O. Henry’s alleged latest writings, too. In an introduction signed by “Parma”—Pratt’s pseudonym—he brushed off nonbelievers and any skeptics who might have found the prose style different from O. Henry’s. The spirit world, Pratt explained, simply inspires a different voice; furthermore, the stories prove that a leopard can change its spots.

3. Hope Trueblood (1918) // Patience Worth and Pearl Curran

Also dictated through a ouija board was Hope Trueblood, just one of many works of fiction purportedly penned by the spirit Patience Worth in 1918. Arguably one of the most famous of spirit authors, Worth supposedly communicated through Pearl Curran, a housewife who lived in St. Louis. From 1913 through 1937, Curran dutifully recorded books, plays, poems, and short stories, at times receiving and scribbling thousands of words in one session.

Hope Trueblood, which told the story of a girl in mid-Victorian England searching for her father, stands out from the rest of Worth’s oeuvre. The spirit was known for her archaic language and typically set stories far in the past: Telka occurred in medieval England; The Sorry Tale was set in the days of Jesus. Hope Trueblood unfolded in the present era (when originally published) and Worth employed plain English for the first time. Like many of her works, the novel received critical acclaim.

Hope Trueblood, however, also drew more skeptics than Worth’s previous works. What would the spirit of a 17th-century English woman (whose spirit claimed she had immigrated to America, where she was killed in a Native American raid) know of Victorian life? Yet people had difficulty explaining how Curran, who had little education and opportunity for travel, wove these stories that contained detailed, accurate descriptions of distant settings. The mystery captivated Worth and Curran’s readers, and it went with Curran to her grave. When she passed away in 1937, the headline of her obituary in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat read “Patience Worth is Dead.”

4. To Woman (1920) // Meslom and Mary McEvilly

An American medium in Paris known as Mary McEvilly received messages from a mysterious spirit named Meslom during a number of sessions held between October 1919 and March 1920. They form To Woman, a book describing the duties of the female sex to help better the world and lead mankind to salvation. Lofty, abstract statements fill the 108 pages, and Meslom’s often-repetitive ramblings are arduous to read. Overall, the spirit argued that women are responsible for human's spiritual progression since they are in more in touch with nature and have greater intuition than men, who have more highly developed powers of reason.

McEvilly identifies Meslom as a man, and although he praised women for their sensitivities, he also betrayed sexist attitudes: Man will always be master, and women should surrender any hope of gender equality, he tells McEvilly; although they have good judgment, women will never make laws; women who steadily pursue an education may weaken their innate connection to all that is good. Most rewarding, he suggests, would be for a woman to instead pray frequently for knowledge that leads to spiritual development and happiness.

Curiously, To Woman emerged a few months before women in the U.S. received the full right to vote. Little record of Mary McEvilly exists, but her book must have come off as backward to more than a few people even when originally printed.

5. A Wanderer in the Spirit Lands (1896) // Franchezzo and A. Farnese

Victorians would find a chilling moral lesson in A Wanderer in the Spirit Lands, supposedly dictated to one A. Farnese by an Italian man who had recently passed away. Identified only as Franchezzo, his spirit filled over 300 pages with vivid descriptions of his lonely, miserable journey through the spirit world. Those dark travels were his deserved punishment, he writes, as he had lived a selfish life in worship of the material rather than of God.

Franchezzo initially ventures into the cold and decaying realms of hell, and only through laborious works of atonement eventually passes through bright heavenly gates. His tale served as an engrossing sermon, warning its readers of the terrible fate that awaits if they did not start changing their sinful behavior while on Earth—before it was too late.

6. Ouina’s Canoe and Christmas Offering, Filled With Flowers for the Darlings of the Earth (1882) // Ouina and Cora L.V. Richmond

One of America’s most beloved spirits, Ouina was believed to be a young Native American girl who spread tens of thousands of uplifting messages from the spirit world. Beginning in 1851, she spoke through Cora Lodensia Veronica Scott, a famous Spiritualist from New York who had begun channeling spirits at a young age and launched a career as a trance lecturer (someone who performed public lectures supposedly received from the spirit world). Scott’s audience was often people who had lost loved ones; her romantic poems and tales painted the afterlife as a place filled with beauty and joy, offering mourners some comfort and rest from grief. Ouina’s Canoe was the first published collection of a handful of the spirit’s works, set to print at Christmas time as her gift to help and heal more people.

Along with verses filled with flowers, sunbeams, moonbeam fairies, and morning stars, the book included a biography of Ouina. Her own story was one of sorrow: Her mother had died in childbirth, and her father, chief of a tribe that resided along the Shenandoah River, decided to sacrifice Ouina when she was about 15 to save his people from misfortune. With her touching history and messages of peace and love, it’s unsurprising that Scott’s guide received such great adoration, rather than cynical criticism.

7. Jap Herron (1917) // Mark Twain and Emily Grant Hutchings

The author of works like The Prince and the Pauper and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn apparently couldn’t resist putting pen to paper even after death: Mark Twain, who died in 1910, supposedly dictated Jap Herron to Emily Grant Hutchings (who happened to be a friend of Curran’s) and Lola V. Hays (who was, in the words of a New York Times review published as the time, “the passive recipient whose hands upon the pointer were especially necessary”) through a Ouija board. The novel, published in September 1917, was set in Twain’s home state of Missouri, “and tells how a lad born to poverty and shiftlessness, by the help of a fine-souled and high-minded man and woman, grew into a noble and useful manhood and helped to regenerate his town,” according to the Times. Twain’s publisher sued in 1918, and Hutchings ceased publishing the book.

A version of this story ran in 2016; it has been updated for 2023.