On the morning of December 29, 1916, Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin was startled by a phone call that turned out to be yet another death threat. His daughter, Maria, later remembered that it put him in a bad mood for the rest of the day. That night, at 11 p.m., he gave her a final reminder before she went to sleep: He was going to the Yusupov Palace that evening to meet an aristocrat. It was the last time she saw him alive.

Two days later, a search party found a body trapped beneath the ice of the frozen Malaya Nevka River. It was Rasputin: missing an eye, bearing three bullet wounds and countless cuts and bruises. The most infamous man in Russia was dead, assassinated at age 47.

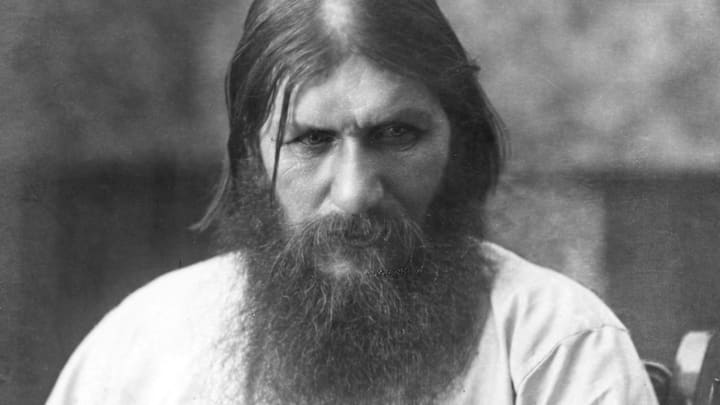

Over a hundred years after his murder, the legend of Russia’s “Mad Monk” has only spread, inspiring films, books, operas, a disco song, and even his own beer, Old Rasputin Russian Imperial Stout. Described by early biographers as “The Saint Who Sinned” and “The Holy Devil,” he remains a difficult man to define. He spent less than a decade in public life, was barely literate, and published only two works. Even within the Russian Orthodox Church, the debate continues: Was Rasputin a charlatan, a holy man, the czarina’s secret lover, Satan himself, or just a simple Siberian peasant?

Above all, one question refuses to rest: What exactly happened to Rasputin in the early hours of December 30, 1916?

“The Reincarnation of Satan Himself”

At the turn of the 20th century, Russia was the last absolute monarchy in Europe, and Czar Nicholas II had proven to be an unpopular ruler. Fearful of revolution and mired in corruption, the Romanovs also suffered from another significant problem: Czarevich Alexei, the young heir to the throne, had hemophilia, an incurable and then-deadly blood disease. When doctors failed to cure the boy, Nicholas II turned to alternative methods. Around 1906, he and Czarina Alexandria were introduced to a Siberian holy man. Neither a monk nor a priest, but a peasant pilgrim turned preacher and faith healer, Rasputin made a good impression on the royal couple, and by 1910 was a regular at the Romanov court.

Although the czar, czarina, and even the royal doctors (begrudgingly) believed in Rasputin’s healing abilities, his proximity to the throne inspired suspicion and jealousy among the church, nobles, and the public. Rough in manners, fond of drinking, and prone to flirting and even sleeping with his married female followers, Rasputin’s brazen disregard for social norms caused some to speculate about his intentions. A few people even called him a heretic.

Soon, treasonous rumors began circulating that Rasputin was sleeping with the czarina, had fathered Alexei, and held total control over the czar. With World War I raging, Nicholas II’s departure for the front only increased the sense that it was Rasputin who was really ruling Russia. According to his self-confessed murderer, if the country and the czar were to be saved, Rasputin’s malevolent influence had to be erased—Rasputin had to die.

Prince Felix Yusupov—Rasputin’s self-confessed killer and the czar’s cousin—first published his account of the murder, Rasputin, while living in exile in France in 1927. According to his version of the evening, Yusupov walked Rasputin into the Moika Palace at a little after 1 a.m. Upstairs, Yusupov’s four accomplices—Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, conservative member of the Duma Vladimir Purishkevich, Dr. Stanislaw Lazovert, and army officer Sergei Sukhotin—lay in wait, passing the time listening to “Yankee Doodle Dandy” on a gramophone. Yusupov accounted for their noise by explaining that his wife had a few friends over, then led his victim down into the basement. He’d spent all day setting the scene, and had prepared two treats for Rasputin: a bottle of Madeira and several plates of pink petit fours—all laced with cyanide by Dr. Lazovert.

As Rasputin relaxed, eating multiple cakes and drinking three glasses of wine, Yusupov waited. And waited. The “Mad Monk” should have been dead in seconds, but the cyanide seemed to have no effect. Growing worried, Yusupov excused himself to the other room. He returned with a gun, promptly shooting Rasputin in the back. The other accomplices drove off to create the appearance that their victim had departed, leaving Yusupov and Purishkevich alone at the mansion with what appeared to be Rasputin’s corpse.

A strange impulse made Yusupov check the body again. The moment he touched Rasputin’s neck to feel for a pulse, Rasputin’s eyes snapped open. The Siberian leapt up, screaming, and attacked. But that wasn’t the worst part. As Yusupov wrote in 1953, “there was something appalling and monstrous in his diabolical refusal to die. I realized now who Rasputin really was … the reincarnation of Satan himself.”

To hear Yusupov tell it, Rasputin stumbled out of the cellar door into the snow. Purishkevich fired four shots before their victim finally collapsed in a snow bank. Yusupov fainted and had to be put to bed. When the others returned, the body was tied up, wrapped in a fur coat, thrown in a sack, and dumped off the Large Petrovsky Bridge into the river below. In the end, Yusupov said, it had been the first step to saving Russia.

As if Yusupov’s account of Rasputin’s seemingly superhuman strength wasn’t strange enough, another detail from the murder provided by Maria Rasputin and other authors goes farther. When Rasputin’s body was found, his hands were unbound, arms arranged over his head. In her book, My Father, Maria claimed this was proof Rasputin survived his injuries, freed himself in the river, and finally drowned while making the sign of the cross. Although Maria and Yusupov’s accounts had opposing motives, together they inspired the mythic perception of Rasputin as a man who was impossible to kill.

Despite the popularity of Yusupov and Maria’s stories, they have more than a few problems. According to the 1917 autopsy, Rasputin did not drown; he was killed by a bullet. (While accounts of the autopsy differ, according to the account cited by historian Douglas Smith in his new book Rasputin, there was no water in the Siberian's lungs.) Although it might seem strange that Maria embellished the events of her father’s murder, she had motives to do so: Rasputin’s legend protected her father’s legacy, and by extension her livelihood. The image of his almost-saintly final moments helped turn her father into a martyr, as Rasputin is currently designated by an offshoot of the Russian Orthodox Church. In the same way, Yusupov’s story had its own audience in mind.

Stranger Than Fiction

When Yusupov published the first version of his “confession,” he was a refugee in Paris. His reputation as “The Man Who Killed Rasputin” was one of his few assets, and it proved so profitable that he became very protective of it. In 1932, while living in the U.S., Yusupov sued MGM for libel over the film Rasputin and The Empress, winning the sole right to call himself Rasputin’s killer. Not only did this lawsuit inspire the mandatory “this is a work of fiction” disclaimer that appears in every American film, it made Yusupov’s claim that he killed Rasputin a matter of legal record. However, even this is a lie. In his memoir, Yusupov admits that Vladimir Purishkevich fired the fatal shot—a fact confirmed in the other man’s account as well.

When one examines Yusupov’s account critically, it’s clear he remade himself the hero in a fantasy battle between good and evil. Comparing the original 1927 account and an updated version published in Yusupov’s memoir Lost Splendor (1953), Rasputin goes from being merely compared to the devil to being the actual biblical antichrist. Even the description of Rasputin’s “resurrection” appears to be a deliberate invention, borrowing elements from Dostoyevsky’s 1847 novella The Landlady.

By making Rasputin into a monster, Yusupov obscures the fact that he killed an unarmed guest in cold blood. Whatever guilt or shame this framing helped ease, some writers suspect it was also a smokescreen to hide the murder’s real motive. The argument goes, if Yusupov’s reasons (saving Russia from Rasputin's malign influence) were really as pure as he claims, why did he keep lying to both investigators and the czarina—claiming he’d shot a dog to explain away bloodstains—long after he was the prime suspect?

A few days after Rasputin’s body was found, the Russian World newspaper ran The Story of the English Detectives, claiming English agents killed Rasputin for his anti-war influence on the czar. The story was so popular that Nicholas II met with the British Ambassador Sir George Buchanan that week, even naming the suspected agent—Oswald Rayner, a former British intelligence officer still living in Russia. In addition to his government ties, Rayner was also friends with Felix Yusupov from their student days at Oxford. Although intelligence reports the czar had received named Rayner as a secret, sixth, conspirator in Rasputin’s murder, whatever explanation Buchanan gave was convincing enough that Nicholas never asked about British involvement again.

Others, then and now, are less certain. The same day The Story of the English Detectives was published, one British agent in Russia wrote headquarters, requesting his superiors at what would become MI6 to confirm the story and provide a list of agents involved. Other oft-cited evidence for British involvement is the claim that Rasputin’s bullet wounds came from a Webley revolver—the standard sidearm for WWI British soldiers. This is far from certain, however: The autopsy could not identify the gun, and surviving photographs are too grainy to make definitive claims about powder burns on the corpse’s skin. Finally, there is the (unauthenticated) letter dated January 7, 1917, from a Captain Stephen Alley in Petrograd to another British officer, which reads: “Our objective has been achieved. Reaction to the demise of ‘Dark Forces’ has been well received.” The letter goes on to name Rayner specifically, saying he is “attending to loose ends.”

Rayner was in fact renting a room at 92 Moika at the time of the murder, and had been in contact with Yusupov. He was not, however, listed as an active agent in an official list dated December 24, 1916. Rayner could have been at the Moika Palace during the murder, and the only certain assertion would be his friendship with Yusupov. Perhaps the best evidence against British involvement, however, is the comment of the Saint Petersburg police chief that the murderers showed the most “incompetent action” he’d seen in his entire career.

Life After Death

Incompetence might answer more questions about Rasputin’s murder than spies or the supernatural. In the rush to ditch his body, the killers forgot to weigh the sack down. Instead, as Smith points out, the fur coat they’d wrapped Rasputin in worked like a natural flotation device, pulling his body up and trapping it under the frozen surface. According to the 1917 autopsy, the body’s various cuts were produced as the corpse dragged against the rough ice. This dragging may have even broken the ropes off Rasputin’s frozen, outstretched wrists.

Incompetence would also explain the last problem with Yusupov’s story. In their memoirs, both Yusupov and Purishkevich wrote about Rasputin’s apparent immunity to poison, which allegedly allowed him to consume the cyanide-laced wine and pastries. But no traces of cyanide were found in the 1917 autopsy. As early as 1934, author George Wilkes said in an issue of The British Medical Journal that Yusupov’s description left only one possibility: Rasputin was never given the cyanide. Wilkes wrote, “If Dr. Lazovert tried to poison Rasputin, he bungled his job.” Nearly 20 years later, Lazovert confirmed these suspicions. He confessed on his deathbed that last-minute conscience and his Hippocratic oath made him switch the powder for a harmless substance.

In the end, Rasputin’s killers got off lightly: Dmitri Pavlovich was sent to serve at the front, while Yusupov was put under house arrest at his Siberian country estate. Lazovert’s confession opens an interesting possibility, however. Did Yusupov, unaware of the missing poison, think he had witnessed Rasputin survive cyanide, planting the seed that inspired his later supernatural additions?

If so, it would seem fitting—time and again, the reactions Rasputin received were based largely on others’ beliefs and expectations. Even in his own time, the myths that surrounded Rasputin eclipsed—and even sometimes created—the reality.

Sources: Rasputin: Faith, Power, and the Twilight of the Romanovs by Douglas Smith; The Life and Times of Grigorii Rasputin by Alex de Jonge; My Father, by Maria Rasputin; Rasputin and the Fall of the Romanovs, by Colin Wilson; “Cyanide Poisoning: Rasputin’s Death,” by R. J. Brocklehurst and G. A. Wilkes.

Read More About History:

A version of this story was originally published in 2016 and has been updated for 2025.