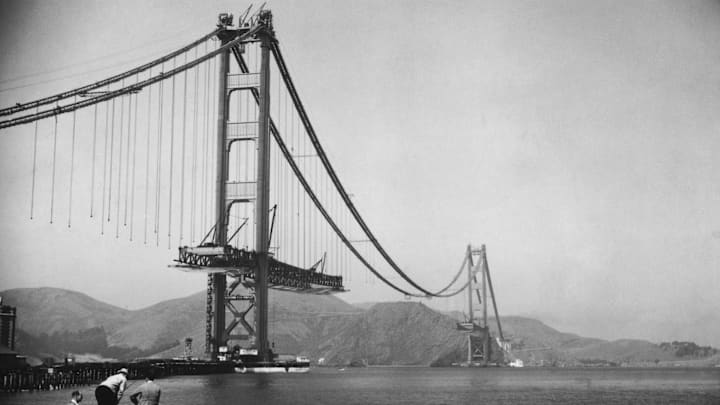

No one could accuse Joseph Bazzeghin of not being ambitious. In 1938, Bazzeghin, a self-styled entrepreneur, delivered a proposal to San Francisco city officials. What their lauded Golden Gate Bridge was missing, he said, was a roller coaster rocketing across its suspension cables.

In Bazzeghin’s mind, the attraction could top out at 220 miles per hour—faster than any roller coaster in existence, with one precipitous drop of 750 feet. The infrastructure was already all there: All the city had to do was make some minor additions, and they’d have one of the biggest and best amusement rides in the country. Or, as he insisted, “[the] ride would be most thrilling experience in any person’s life.”

As crazed as it sounds, city authorities did something unexpected: They took Bazzeghin seriously.

The Rise of Roller Coasters

Roller coasters were a somewhat recent innovation circa the 1930s. These rides built on the “scenic railways” track rides that became popular in the 19th century. Coasters that were propelled at high speeds along tracks came of age with Coney Island’s Cyclone, which could hit over 60 miles per hour.

Bazzeghin’s plan went a step further. An inventor from Hamden, Connecticut, who had peddled steam engines and an early version of a jet pack, he believed the Golden Gate Bridge could accommodate a coaster via the existing towers, thus eliminating the initial cost of building and engineering a supporting structure. But it was also a purposeful bit of promotion: San Francisco's Treasure Island was due to host the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition, a kind of world’s fair designed to draw attention to the city and its amenities. Just as Olympic cities erect buildings, San Francisco could deploy a roller coaster.

Actually, two of them.

An Off-the-Rails Idea

Bazzeghin’s pitch, which he remitted to city authorities at the Department of Public Works in the summer of 1938, involved putting coasters on both the newly-built Golden Gate Bridge and the Oakland Bay Bridge, where tracks would be added to the suspension cables. For the latter, he envisioned adding an elevator that would go to the top of the third tower, where attendees could board a car going 220 miles per hour. There would be seven total drops, including one that plunged 500 feet. The car would also briefly be submerged under water in the San Francisco Bay. The Golden Gate Bridge coaster, which Bazzeghin dubbed the Bolt, would be similar, minus the aquatic intermission [PDF].

“if you look at a suspension bridge, especially the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge with its four towers and three main spans, you will see that the sagging cables thereof likewise consist of a series of high ridges at the tops of the towers and of low valleys at the center of the spans, thus making it possible to operate a ride thereon similar to a roller coaster,” Bazzeghin wrote. “The natural cable sag on suspension bridges is sufficiently steep to provide a thrilling ride, and is not so steep as to scare people away as is the case with roller coasters.”

Bazzeghin even went to the trouble of pre-emptively countering what he anticipated would be the city’s arguments. Safety? It was no more dangerous, he insisted, than erecting a tall building or expanding railroad track. Expensive? The supporting structure was already built. The bridges were never meant to host a roller coaster? “This is not a sensible reason for opposing this ride, because new developments are continually being added to old or completed structures, including bridges, to improve and bring them up to date, and so [there's] no reason to discriminate against on this account.”

It was, he concluded, an “extremely simple affair.” The entire operation could be secured to the bridges using “clamps.”

“Too Great an Attraction”

Despite his proposal being peppered with confident words like therefore and thus, city officials had concerns. For one thing, the city didn’t even allow pedestrian foot traffic on the Bay bridge, let alone a car full of them shooting across the suspension cables. Some expressed fear patrons would wind up flying out of the coaster, or that passengers might suffocate from the wind resistance or otherwise succumb to “nervous tension.”

There was also the problem of the motorists traveling below. “There are several objections to your proposal,” engineer C.H. Purcell wrote in a stoic response. “A sufficient one is the fact that the cars on the coaster moving at the speeds you propose [175 to 200 miles per hour] would so distract the operators of motor vehicles on the bridge as to increase the probability of accident ... on this ground alone, we would be forced to reject your proposal.”

Bazzeghin scoffed at the fears, dismissing them as “the usual resistance which obstructs the acceptance of all new ideas.” Driver distraction, he wrote, was a non-issue since the cars would be in line of sight of drivers and they're often “gaping” at the towering structure anyway. He even inferred that the lack of structural concerns meant his idea was sound—so sound that the only problem is that it was too great a spectacle.

“You directly admit this project has no serious faults,” Bazzeghin fired back. “It is being rejected because it is too great an attraction … it is too good.”

But it was not to be. After deliberation, the Toll Bridge Authority vetoed the idea.

“While doubtless you are conscientious in your own conception of the feasibility of the proposed enterprise, yet, acquainted as we are with the physical, financial, and legal features of the bridge, we do not consider your project adaptable thereto,” the Authority’s director wrote.

It was unlikely Bazzeghin’s ambitions could have ever been realized. In 2013, amusement park expert Greg Sanders told CBS such a project would have cost hundreds of millions and was likely a practical impossibility.

Bazzeghin’s future was never well-documented, though his aptitude for keeping motorists safe was later called into question. In 1945, a stepladder poking out of his truck prompted a vehicular accident.

Read More About Amusement Parks: