Though it’s difficult to imagine, Washington, D.C., wasn’t always the capital of the United States. During the Revolutionary War, the 13 Colonies didn’t really have a capital: the Continental Congress moved its meeting locations from Philadelphia to Baltimore to smaller Pennsylvania cities to avoid the march of British soldiers.

How Did D.C. Become the U.S. Capital?

Washington, D.C., was born only after the war as the result of a compromise over two key issues between Congress members from the Northern and Southern states. First, Northern lawmakers didn’t want the new nation’s capital in a Southern slave state, and Southerners preferred a site on the Potomac River between Maryland and Virginia (both slave states) so they could maintain proximity to the seat of power. Second, Northerners wanted the federal government to assume outstanding war debts from the revolution, and Southerners, having already paid off most of their own debts, wanted Northern states to shoulder their own burdens.

Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, and Representative James Madison of Virginia then negotiated the Compromise of 1790. Madison agreed to convince Southern lawmakers to allow the federal government to assume Northern states’ war debts, and Hamilton agreed to support the placement of the nation’s capital, a district to be named after the explorer Christopher Columbus, on the banks of the Potomac. Congress soon passed bills to these effects.

That’s not to say the capital would “belong” to the South, though. Despite their conflicting views on governance, neither the Federalists nor the Democratic-Republicans—the two dominant political parties at the time—wanted the capital to become part of a particular state. Doing so could render the federal government susceptible to state politics while, at the same time, giving that state special powers over others.

Instead, as stipulated in the “Seat of Government” clause of the U.S. Constitution, the Founders created a district: a territory “not exceeding 10 miles square” that could “exercise like authority” over itself. Like states, the District of Columbia could draw up its own legislation, manage its own police force, operate its own public services, run its own court system, and elect local officials.

But while the District was given the same responsibilities as a state, it did not have all of the same rights. Residents of the U.S. capital were granted the right to vote in presidential elections by the Twenty-Third Amendment, ratified in 1961, but they have no representation in Congress save for a single, non-voting delegate in the House of Representatives. Congress also retains the right to review—and block—legislation drawn up and approved by D.C.’s local government. The feds have exercised this right to prohibit local taxation of medical marijuana sales and barred needle-exchange programs to reduce HIV/AIDS, among other initiatives.

While the Founders avoided a constitutional crisis by turning the U.S. capital into a district, they created second-class citizenship status for D.C.’s residents. “For over 200 years,” according to the campaign for D.C. statehood, “we have been denied a voice in our national government and sovereignty over our local affairs.”

Is Washington a City in the District of Columbia?

These days, the terms Washington and D.C. are used interchangeably, but they once applied to different entities.

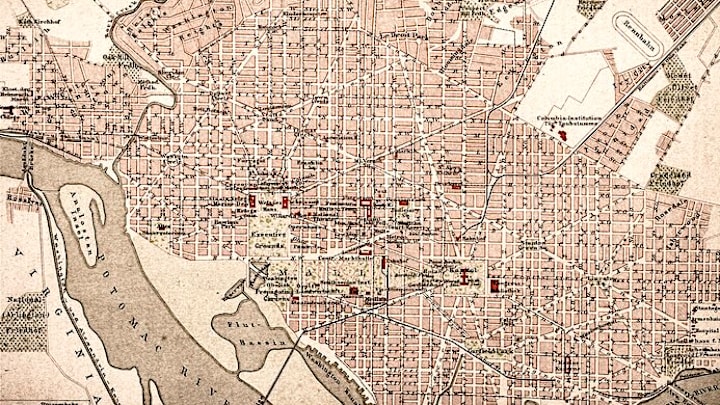

The Constitution mandated that the new District of Columbia would be 100 square miles, and President George Washington chose the specific site at the confluence of the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers dividing Maryland and Virginia. Maryland ceded 69 square miles and Virginia gave 31 square miles to the federal government to establish the District in 1801.

Two cities—Georgetown, Maryland, and Alexandria, Virginia—already existed within the ceded land. The City of Washington (the area encompassing the numbered and lettered streets) was chartered within the District in 1802. The rest of the District was divided into Washington County, D.C. (formerly Maryland), and Alexandria County, D.C. (formerly Virginia), both of which no longer exist.

The state of Virginia clawed back the county and city of Alexandria in 1846, after a decades-long dispute over slavery and the disenfranchisement of former Virginians living in the District who had no state-given rights. The Retrocession of 1846 left just the Maryland-ceded portion of the District north of the Potomac.

The cities of Georgetown and Washington remained their own separate entities within the District of Columbia until 1871. That year, Congress passed the District of Columbia Organic Act [PDF], repealing both of those cities’ charters and expanding the municipal boundaries of the City of Washington to match those of the District of Columbia—making Washington and D.C. essentially the same thing.

Discover More Geography Facts: