In the spring of 1975, detectives with the Tampa police department were cracking down on a rash of obscene material. Among their targets: Jaws, the bestselling thriller about a killer shark that had been released in 1974.

It wasn’t the prose that was explicit. Instead, Tampa’s mayor had paved the way for authorities to have the book removed from shelves because of its cover—an illustration of a tiny, seemingly nude swimmer cutting through the water as a great white moves in for the kill.

Cover Story

The local dust-up over Jaws was the result of a Tampa anti-obscenity ordinance that had passed in February 1975 making it illegal to display “offensive sexual material” where anyone 17 or under could view it.

Among the infractions under Article IV of Chapter 24 of the City of Tampa Code was “the wearing of any costume or garment which by virtue of construction or transparency of material exposes, exhibits, displays, or reveals the nipple of the (female) breast or the pigmented area adjacent thereto.” Those caught in violation risked $200 in daily fines and a misdemeanor charge.

The ordinance was championed by Tampa’s then-mayor, Bill Poe, to keep explicit content away from younger residents. Tampa police were also alleged to have rounded up an issue of Time magazine featuring singer Cher wearing a sheer dress, a Mickey Spillane detective novel, and author Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying, among others. All featured some degree of nudity.

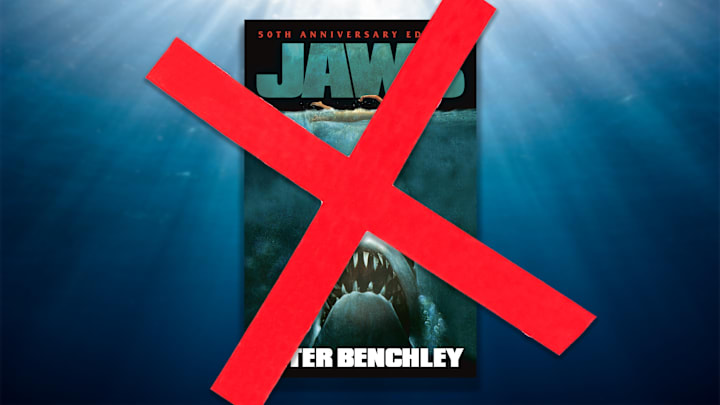

Jaws had been on shelves for a year, and the feature film adaptation was due in theaters in a matter of weeks. The original cover to the book was the work of artist Paul Bacon, who depicted a shark barreling toward a swimmer that Bacon had added to visualize the physical scale of the creature. The composition was later reworked for the paperback version by Roger Kastel, who rendered a less phallic-looking version of the shark and removed the female swimmer’s bathing suit.

That was enough for Tampa’s vice squad to tell store owners to remove it from public display. Though Tampa police denied any widespread order was in effect, one of the city’s attorneys acknowledged that a police officer had the discretion to determine whether something would be covered under the ordinance.

Resurfacing

Naturally, local book and magazine distributors were unhappy. “Jaws has a one-inch nude on the cover,” Robert Salo of Hillsboro News Company told the Tampa Tribune in an attempt to downplay the infraction. Nudity, he added, was a subjective matter. “Would you say that a magazine with a picture of Venus De Milo on the cover or a magazine featuring Michelangelo’s David is sexually offensive?”

Salo didn’t limit his protest to newspapers. He quickly challenged the law in court, alleging the city was forcing such material to be pulled “under threat of criminal prosecution” and that Hillsboro had lost $425,000 in sales since the ordinance was put into effect. One detective stated he had personally made three arrests for violating the ordinance, though it’s unclear whether any of them were Jaws-related.

In March 1975, U.S. District judge Ben Krentzman ruled that Tampa’s ordinance was potentially unconstitutional and issued a temporary restraining order that put a halt to its enforcement. The ordinance was effectively dead in the water, though its brief enforcement did prompt local convenience stores to keep adult magazines under the counter rather than on display.

Later, Kastel would tell Collector’s Weekly that he feared the controversy “was the end of my illustration career.” But Bantam, the publisher behind the paperback release, felt the resulting press attention was good (and free) publicity. The art was used for the Jaws film poster, though a graphic designer did make one key change: adding enough water foam to cover the swimmer’s breasts.

Read More About Jaws: