The sales managers at Doubleday stared at the screen. Projected from a slide was the proposed cover art to Jaws, a forthcoming thriller novel from an unheralded author named Peter Benchley about an aggressive great white shark that terrorizes a small vacation town. At Benchley’s suggestion, the art director had depicted the bleached jawbone of a shark, mouth agape and ready to gorge on tourists.

But the salespeople sensed trouble. To them, it didn’t look like a shark’s mouth. It reminded them instead of a vagina with teeth or the Freudian nightmare known as vagina dentata.

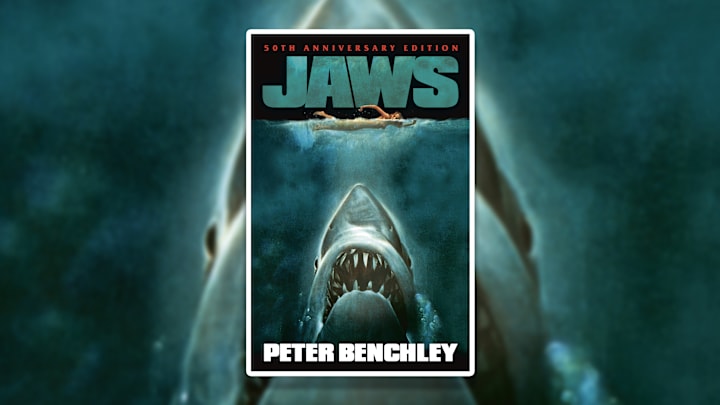

A revised painting with a shark, created just before the book went to print, didn’t fare much better; this time, it invited comparisons to a penis. (The team at Doubleday, it seems, had one thing on their minds.) But eventually, after input and ideas from multiple artists and several iterations, Jaws would feature one of the most iconic book jackets of all time—a shark approaching the surface as a woman swims tantalizingly close to its razor-sharp teeth. The composition was so perfect that it was repurposed for the 1975 Steven Spielberg-directed film adaptation, becoming, in the process, one of the most familiar movie posters of all time.

Despite its stature, the art for Jaws has become something of an enigma. While reproductions are pervasive, finding the original canvas is another story.

An Ocean View

Peter Benchley wrote Jaws to unburden himself from a longstanding curiosity: What would happen, he wondered, if a shark opted to attack a waterfront vacation destination? He enticed Doubleday editor Tom Congdon, who helped shape Benchley’s manuscript from one that went a little too heavy on the humor to a potential bestseller.

That left Doubleday to figure out how best to market the book. The job fell to art director Alex Gotfryd, who in 1973 was supervising over 700 covers annually. Gotfryd was amicable to using Benchley’s idea: the minimalist jawbone of a shark, with his fictional town of Amity trapped between its teeth. (Congdon suggested a more foreboding red sky, which Gotfryd also incorporated.)

The design by artist Wendell Minor was presented during an April 1973 sales conference, where it was met with hesitancy over its anatomical connotations. A worried Congdon conferenced with Gotfryd and suggested that the cover depict an actual shark, flesh and all.

“The cover’s not big enough,” Gotfryd said. “It will look like a sardine.”

In the spirit of compromise, the two settled on a jacket with no illustration, just the title and Benchley’s name. But this proved untenable for a third party: Bantam Books, which had just paid a hefty $575,000 for the rights to publish Jaws in paperback. With just a title on the cover, Bantam publisher Oscar Dystel thought readers might think it was a book about dentistry.

To satisfy Dystel, Gotfryd brought in acclaimed artist Paul Bacon, who had worked on titles ranging from Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five to Joseph Heller’s Catch-22. (He would ultimately be credited with over 6500 cover illustrations.)

Bacon depicted a shark headed for the surface of dark water. To offset Gotfryd’s concern that it might look like a “sardine,” Bacon added a swimmer. That way, readers got a sense of scale. (You can see the cover here.)

Congdon and Gotfryd were resigned. “We realized that the new version looked like a penis with teeth,” Congdon said. There appeared to be an art to the art for Jaws, and they hadn't quite gotten there.

Jaws Revised

The hardcover version of Jaws (priced at $6.95) was a hit shortly after its arrival on bookshelves in February 1974; by April, there were 75,000 copies in print. But the bosses at Bantam thought Bacon’s cover seemed to be missing something. The paperback house—which had a lot of money tied up in Jaws and was hoping to sell 5 million copies in softcover ($1.95) when it was released in January 1975—wanted to go in a slightly different direction.

Bantam art director Len Leone brought on artist Roger Kastel, a Korean War veteran who had been doing illustrations for various publishers. The mandate was to make the shark more sinister, with a mouth full of teeth. (Whether anyone expressly told Kastel to make it look less like a penis is unknown.) Bacon’s composition would remain, but the shark and swimmer needed a makeover.

Kastel went to the American Museum of Natural History to visit the shark exhibit, but it was closed due to museum renovations. So he sketched and photographed sharks, including mako sharks, on an easel instead. (As a result, the illustrated shark is more mako than great white.) The reference made the fictional beast more lifelike, with a wider body and a bigger mouth.

For the swimmer, Kastel seized an opportunity. While taking pictures of a model for Good Housekeeping, he requested that she balance herself on a stool and mimic a front crawl paddle. He put the images together in a bright blue ocean, a departure from the black sea of Bacon’s work.

The oil painting also differed in another significant way: Kastel subtracted the swimmer’s bathing suit. Though no genitalia was shown, it’s clear that the swimmer is enjoying the water in the nude. That proved too much for some cities, resulting in the paperback being banned in more conservative markets. In Tampa, Florida, for example, an anti-obscenity statute passed by the city council saw copies removed from shelves, along with copies of Time magazine featuring the singer Cher in a form-fitting dress.

“I thought that was the end of my illustration career,” Kastel told Collector’s Weekly in 2012. “Boy, was I ever wrong. Bantam loved the publicity. It was great for book sales.” But Kastel’s satisfaction would prove short-lived.

A Disappearing Canvas

Kastel’s image so perfectly captured the interspecies conflict that Universal, the studio behind the film adaptation, used it virtually unchanged as the movie poster, save for a bit of water foam obscuring the swimmer’s breasts. (The title font, however, is altered: The j is rendered to resemble a fishhook.) Bantam’s Oscar Dystel was perhaps a little too generous with the art, letting Universal use it at no charge. Then again, the movie was essentially free advertising for Bantam’s paperback.

But that decision would have a radical impact on the fate of the original art. According to Kastel, his last glimpse of his original work came while the painting was part of a book tour. Then, it was shipped to Universal. And after that, Kastel said, he never saw it again.

Kastel believed the artwork could have been misplaced in Universal’s archives. A more distressing theory is that someone in or around the studio simply purloined it.

In a 2022 article for Daily Art Magazine, Kastel’s son, Matthew Kastel, wrote that his father had attempted to seek answers from Universal via Oscar Dystel, the Bantam publisher. But Dystel only said that Universal executives had no knowledge of the painting’s whereabouts. In the piece, Matthew argued that his father is the rightful owner of the work and urged Universal to search for it.

The painting has yet to surface; Kastel died in 2023. While his missing Jaws piece—which would almost certainly fetch millions at auction if it’s ever found—remained a sore spot, the assignment led to another indelible piece: the poster for 1980’s Star Wars sequel The Empire Strikes Back.

Read More Articles About Art in Pop Culture: