Joseph Weizenbaum wasn’t sure what to make of what his secretary was saying. It was the late 1960s, and the MIT computer scientist had completed work on ELIZA, the world’s first autonomous computer chat program. With 200 lines of code, ELIZA was capable of holding up one end of a conversation with a human. The program was rudimentary but effective—perhaps too effective.

Weizenbaum’s secretary had asked him to leave the room. She wanted to confide in ELIZA privately.

Artificial intelligence, which has dominated the technological conversation for decades, is having a moment thanks to ChatGPT. The chatbot is capable of some impressive feats, from impersonating historical figures to writing surprisingly literate essays. At its most innocuous, ChatGPT is a fun diversion. At its most sinister, it might make some jobs obsolete while fundamentally altering how users ascribe human traits to machines.

Weizenbaum anticipated the latter. He was born in Berlin, Germany, in 1923, and fled the country with his family in 1935 to escape Nazi rule. They ended up in the United States. After a stint in the Army Air Corps as a meteorologist, Weizenbaum resumed his formal education and applied his considerable math skills to the burgeoning computer industry. Computers of the time—giant, room-spanning mainframes—were in their infancy but already demonstrating their potential for commercial and educational use. In 1955, Weizenbaum assisted General Electric in the design of the first computer used for banking.

Later, as a visiting associate professor of computer science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Weizenbaum began exploring the possibilities of these computers to have English-language interactions with your average person, which was not possible at the time. To “talk” to a computer at that point usually meant learning a programming language.

The best way of achieving a conversation between a computer and a human, Weizenbaum believed, was to mimic the repetitive structure of a psychoanalysis session, with the program repeating words and rephrasing statements given to it in the form of a question. The idea, he said in 1984, was to have a program that didn’t need a deep reservoir of knowledge. The concept needed “conversations in which one of the parties doesn’t have to know everything, and a psychiatrist occurred to me. Maybe if I thought about it 10 minutes longer, I would have come up with a bartender.”

He used a proprietary programming language he named MAD-SLIP to create the program. He called it ELIZA after the character Eliza Dolittle—a flower seller who is taught proper elocution, among other social graces, by Professor Henry Higgins—from George Bernard Shaw’s 1913 play Pygmalion. (An adaptation of the play, the musical My Fair Lady, debuted in 1956, with the movie version hitting theaters in 1964.)

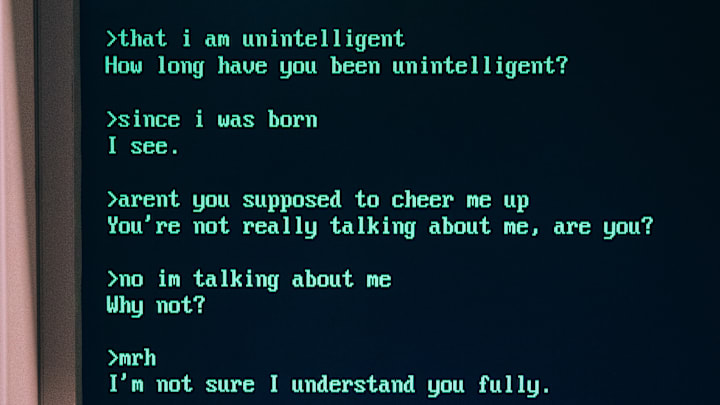

Weizenbaum debuted ELIZA in 1966. He invited MIT students as well as colleagues to interact with the program. Messages were sent to the mainframe computer under a time-share system [PDF], which allowed the hardware to host multiple users at once. The statements were then analyzed by ELIZA and sent back to an electric typewriter and printer. Words like girlfriend, depressed, what, mother, and father could all elicit responses. If ELIZA was at a loss, it could fall back on Please go on or That’s very interesting or I see, much like a disinterested human conversation partner. Users had to be careful not to use a question mark, which would be interpreted as a line delete request.

A sample exchange went like this:

User: Well my boyfriend made me come here.

ELIZA: Your boyfriend made you come here?

User: He says I’m depressed much of the time.

ELIZA: I am sorry to hear you are depressed.

User: It’s true. I am unhappy.

ELIZA: Do you think coming here will help you not to be unhappy?

While laborious by today’s standards of instant text messaging, at the time it was a tantalizing flirtation with machine intelligence. But Weizenbaum wasn’t prepared for the consequences.

Time and again, those testing ELIZA grew so comfortable with the machine and its rote therapist-speak that they began to use the program as a kind of confessional. Personal problems were shared for ELIZA’s advice—really, the program’s ability to listen without judgment.

Weizenbaum took care to explain it was just a program, that no human was on the other end of the line. It didn’t matter. People imbued ELIZA with the very human trait of sympathy.

This observation might have pleased ELIZA’s inventor, save for the fact that he was troubled by a person’s willingness to conflate a program with actual human relationships. Having escaped the tyrannical rule of Nazi Germany, he was perhaps specially attuned to the dangers of reducing the human factor in society.

As a result, ELIZA became something of a sore point for Weizenbaum, who shifted his attention toward assembling critiques of ushering out human thought too quickly and giving too much credence to the illusion of intelligence.

“There are aspects to human life that a computer cannot understand—cannot,” Weizenbaum told The New York Times in 1977. “It’s necessary to be a human being. Love and loneliness have to do with the deepest consequences of our biological constitution. That kind of understanding is in principle impossible for the computer.”

In ELIZA’s case, that could sometimes be accomplished with time. After a dozen or so exchanges, the program’s limitations began to show themselves and the conversation grew more stilted. The same held true of PARRY, a chatbot introduced by Stanford psychiatrist Kenneth Colby in 1971, and one that was indelicately meant to mimic the behavior of a person with paranoid schizophrenia. In 1973, the two programs were brought together to converse with one another as “doctor” and “patient”:

ELIZA: Good Evening. Tell me your problems. Please terminate input with a period or a question mark.

PARRY: People get on my nerves sometimes.

ELIZA: I am not sure I understand you fully.

PARRY: You should pay more attention.

ELIZA: Suppose you should pay more attention.

PARRY: You’re entitled to your own opinion.

ELIZA: What makes you think I am entitled to my own opinion?

By the mid-1970s, Weizenbaum was sufficiently concerned about the trajectory of artificial intelligence that he authored the 1976 book Computer Power and Human Reason: From Judgment to Calculation, which argued computers can never be omniscient. Humans, he said, needed humans to address human problems. While this wasn’t the only objection heard with regard to computers, it was one of the rare times a computer scientist was sounding the alarm.

ELIZA gained some renewed attention in 1980, when the burgeoning world of personal computers made a chat program appealing to a mass audience. Radio Shack offered an ELIZA program that ran on their TRS-80 computer. It also offered a “talking ELIZA” option, which offered synthesized speech through speakers.

Radio Shack probably didn’t have a customer in Weizenbaum. At the time of his death in 2008, he was still cautioning of the perils of reckless technological evolution. Perhaps ChatGPT would have provided him more ammunition—or perhaps he found all he needed when his secretary asked to be alone with a couple hundred lines of code.