It’s not just episodes of Law & Order that can be ripped from the headlines. For some authors, the idea for a new novel can be found by turning on the news, taking in a documentary, or flipping open a history book. From hostage situations to serial killers to accusations of witchcraft, real-life events provided the inspiration for the books on this list.

1. The People in the Trees // Hanya Yanagihara

When writing her 2013 debut novel—about a brilliant researcher who unravels the secret of a jungle-dwelling tribe that seemingly possesses the key to immortality—Hanya Yanagihara drew on the story of real-life scientist Daniel Carleton Gajdusek. Gajdusek researched kuru, a deadly brain disease present in members of New Guinea’s Fore people that was caused by cannibalization rituals, in the late 1950s; he was later able to transmit the disease to chimpanzees in the lab and won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work in 1976. Yanagihara told Vogue that she knew about Gajdusek through her father, who worked at the National Institutes of Health in the 1980s.

Gajudesk adopted as many as 57 children, most of them boys, from Papua New Guinea, and brought them to the U.S., where he raised them. As an adult, one of those boys accused Gajdusek of molesting him; the scientist took a plea agreement, pleading guilty and serving a year in prison before being released, after which he left the United States.

“Gajdusek’s story fascinated me,” Yanagihara said. “Here was an indisputably brilliant mind who also did terrible things. It’s so easy to affix a one-word description to someone, and it’s so easy for that description to change: if we call someone a genius, and then they become a monster, are they still a genius? How do we assess someone’s greatness: is it what they contribute to society, and is that contribution negated if they also inflict horrible pain on another? Or—as I have often wondered—is it not so binary?”

2. Moby-Dick // Herman Melville

When Herman Melville was writing Moby-Dick—in which an obsessed captain hunts a white whale that ultimately sinks his ship—he drew on two real-life whale tales. One was a 70-foot-long white sperm whale named Mocha Dick that would attack whale boats when they brought out their harpoons (the whale had around 19 harpoons in it when it was eventually killed in the late 1830s). The other was the 85-foot-long sperm whale that rammed and sank the whale ship Essex in November 1820, leaving its crew stuck in the middle of the Pacific Ocean in small whaling boats with little food or fresh water. They spent 89 days at sea, during which they had to resort to cannibalism to survive.

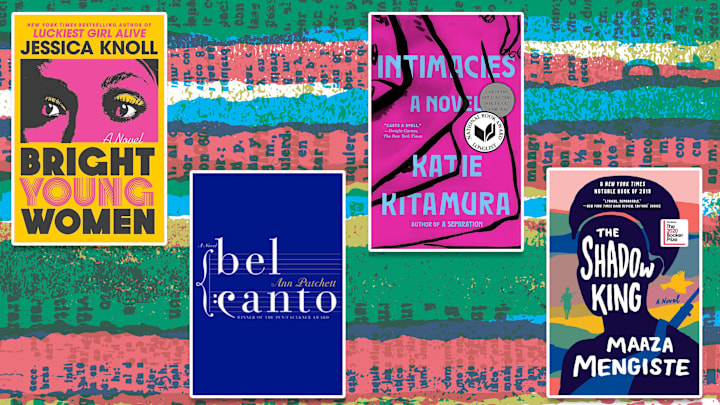

3. Intimacies // Katie Kitamura

Katie Kitamura’s 2021 novel Intimacies, about a translator working the trial of a dictator at The Hague, was inspired by the real-life trial of Charles Taylor, the former president of Liberia. As she listened on the radio to him speaking at his trial, “I had such a clear sense of a performance taking place,” she told The New York Times. To write the novel, she visited the Hague and posed questions to real interpreters who worked with war criminals.

4. Bel Canto // Ann Patchett

In December 1996 and into 1997, author Ann Patchett watched, rapt, as a crisis unfolded in Peru: Terrorists with the Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement entered the home of the Japanese ambassador in Peru while a party was in progress and took hundreds of people hostage; eventually, they released all but 72 people and hunkered down for months. The crisis ended in April 1997 when special forces attacked the rebels in the compound, killing all 14 of them.

Patchett took that event and loosely adapted it into her award-winning 2001 novel Bel Canto, in which terrorists in an unidentified South American country storm a party for a visitor from Japan who loves opera—and specifically, the opera singer performing at the party. The terrorists are looking for the country’s president so they can take him hostage, but the president isn’t present. The terrorists dig in; as the months go by, both they and the hostages let down their guard—at least with each other.

“I definitely have a theme running through all my novels, which is people are thrown together by circumstance and somehow form a family, a society,” Patchett told Gwen Ifill in 2002. “They group themselves together. So as I’m watching this on the news, it was as if I was watching one of my own novels unfold. I was immediately attracted to the story.”

Patchett said “about 98 percent” of the book was fiction, including the presence of the opera singer. “I thought ‘this is so operatic what’s happening in Lima. The only thing that's missing from this story is an opera star hung up with the rest of these people,’” she said, “which is the nice thing about being a novelist instead of a journalist. When you see a story that is crying out for an opera singer, you just stick an opera singer into the story.”

5. The Island of Doctor Moreau // H.G. Wells

Sci-fi author H.G. Wells, who also had a degree in zoology, paid close attention to the debate in the UK over whether vivisection—operating on live animals for medical research—should be allowed. At the same time, there was growing acceptance of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. Wells wove it all into 1897’s The Island of Doctor Moreau, a then-shocking tale of a scientist who carries out horrific experiments to create animal-human hybrids. The titular character was described by one critic as “a cliché from the pages of an anti-vivsectionist pamphlet,” and he may have been based on a real scientist: David Ferrier, a Scottish neurologist who experimented on the brains of monkeys and other animals. Because he did not get a certificate of permission to perform some of his experiments, Ferrier was tried under the 1876 Cruelty to Animals Act, but was ultimately acquitted.

6. Bright Young Women // Jessica Knoll

In her third novel, Bright Young Women author Jessica Knoll—who previously published Luckiest Woman Alive (2015) and The Favorite Sister (2018)—takes on serial killer Ted Bundy, who assaulted, raped, and murdered multiple women between 1974 and 1978, sometimes by pretending to be injured. But rather than focus on Bundy himself, Knoll’s story revolves around the survivors of his crimes, imagining what they did in the days afterward and how his crimes changed them. And she never refers to him by name.

The author told Vanity Fair that it all started when she watched Conversations With a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes, and wanted to find out more. Once she began researching, she figured out “that a lot of what we knew about Ted Bundy had been grossly exaggerated in terms of his intelligence, his charm, and even his scholastic aptitude,” she said. “I was also bothered by the fact that it was suggested that how he got his victims had to do with his looks and his charm when it was very extensively documented that he would pose as injured, and solicit women for help.”

Witness interviews revealed that his victims clearly weren’t charmed by him but were instead annoyed. “I find it hard to say no to someone who asks for my help in 2023,” Knoll told TIME. “Imagine women in the 1970s who are being taught to be helpful and polite. It’s a disservice to the victims to write about them like they were lovestruck.” The author reached out to Kathy Kleiner, one of the women Bundy assaulted, before writing Bright Young Women. “Kathy’s mindset was don’t shy away from it,” Knoll said. “I think she feels overlooked by history, and that it’s important that people bear witness to what was done to her and to her sisters.”

7. Inland // Téa Obreht

Téa Obreht was listening to the podcast Stuff You Missed in History Class when inspiration struck. The episode was partially about the camel corps, an experiment by the U.S. Army to use the animals in desert areas of America. The program got an assist from Mississippi Senator and future president of the Confederacy Jefferson Davis, who secured $30,000 that was used to purchase camels overseas and bring them to the states in 1856.

According to an Army blog post about the camel corps, the camels did well in tests in bases in Texas because they “needed little forage and water compared to mules. They could also ford rivers much easier without a fear of drowning and could carry heavier loads.” Future Confederate General Robert E. Lee, then a lieutenant colonel, even used the animals for long-range patrol. But the program ultimately ended when the Civil War broke out; some of the camels were sold, and some escaped. There were sightings of the feral camels reported as late as the 1940s.

When she was writing her novel Inland—a supernatural spin on the American West that takes place in the Arizona Territory in the 1890s—Obreht made the camel corps a large part of the story. “It’s incredibly fascinating, yet it has no pride of place in the mythology of the Old West,” she told the LA Review of Books. “It struck me how strange and interesting it was that a living creature could be in the background of all this social and technological change—and be an unknown constant, just hiding out in the wilderness. And that idea seized me. I couldn’t shake it.”

8. The Shadow King // Maaza Mengiste

Maaza Mengiste’s Booker Prize–nominated The Shadow King takes place during the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 and follows a woman who became a soldier in the conflict. “I grew up with the stories of a poorly equipped Ethiopian military confronting one of the most technologically advanced militaries in the world at that time, and for a child this was a story that felt epic,” Mengiste told the literary journal Brick. “We were not supposed to win, and yet we did.” When she left Ethiopia and moved to the United States, the stories “carried me through some difficult times as an immigrant, as a young girl who was Black in a town that didn’t understand her.”

To write the novel, Mengiste did years of research into both Ethiopian and Italian history and even threw out an early draft. “I wanted to make sure that I knew enough to develop a full history,” she told The New York Times. “I was trying new things, and I told myself to forget everything, forget the way you think you’re supposed to write a novel and do what you really want to do.”

9. Murder on the Orient Express // Agatha Christie

Agatha Christie’s novel Murder on the Orient Express has detective Hercule Poirot trying to figure out who murdered a man on the luxury rail line. The victim turns out to be a kidnapper who had taken a toddler from her parents and extorted cash from them for the baby’s safe return. But after the child’s body is found, one parent dies in childbirth while the other dies by suicide.

Some of the details and plot of the novel were ripped straight from the headlines about the 1932 kidnapping and death of Charles Lindbergh, Jr., son of pioneering aviator Charles Lindbergh. The baby was taken from his crib, and the Lindberghs paid ransom money the kidnappers had demanded in a note left in the child’s room. Sadly, the body of the 20-month-old was discovered two months later, just a few miles away from the Lindberg home.

10. The Lowland // Jhumpa Lahiri

Jhumpa Lahiri was born in London, but growing up, she frequently visited her parents’ native India. On one of these trips, she heard about an incident in the 1970s in which two brothers active in the radical communist Naxalite movement were executed not far from her grandparents’ home—while their family watched. “That was the scene that, when I first heard of it, when it was described to me, was so troubling and so haunted me,” Lahiri told NPR, “and ultimately inspired me to write the book.”

The author did, however, make some adjustments for her story. The real-life event was “the seed of the book,” she told Goodreads, “and it incorporated both place and character and event in different ways. I chose then to work with it to suit my own needs.” Instead of having both brothers be involved in the Naxalite movement, Lahiri opted to have just one of the brothers get involved, which she thought was more interesting. “I took what I knew—which wasn’t a whole lot—and went from there,” she said.

11. A Song of Ice and Fire // George R.R. Martin

With A Game of Thrones (the first book in his A Song of Ice and Fire series) author George R.R. Martin wanted to write a book that didn’t gloss over the brutality of medieval Europe—and for inspiration, he turned to history. The Wars of the Roses was “the single biggest influence” on the story; Martin was greatly inspired by books that Thomas B. Costain wrote about the Plantagenets. “It’s old-fashioned history,” Martin told The Guardian. “He’s not interested in analyzing socioeconomic trends or cultural shifts so much as the wars and the assignations and the murders and the plots and the betrayals, all the juicy stuff.”

Even specific events in the books have historical influences: The Red Wedding, which appears in A Storm of Swords, was based on both the Black Dinner of 1440—a dinner-turned-trap that ended in the murder of two children—and the Massacre of Glencoe of 1692, during which soldiers claiming to need shelter due to a full fort slayed their hosts. “No matter how much I make up, there’s stuff in history that’s just as bad, or worse,” Martin said in 2013.

12. Everyone Knows Your Mother Is A Witch // Rivka Galchen

Astronomer Johannes Kepler—who gave us the three laws of planetary motion—is one of the most famous scientists of all time. Less famous is the fact that his widowed mother, Katharina, was thrown in prison on charges of witchcraft in 1620. Rivka Galchen, Columbia professor and author of 2008’s Atmospheric Disturbances, read all about it in Ulinka Rublack’s The Astronomer and the Witch. Galchen told Powell’s that she was “seized by Katharina's story. I dropped everything I was working on, and just wanted to learn more.”

The author used real historical documents to craft the depositions given about and against Katharina. “What I found moving is that you can actually see, in the deposition of the tailor, for example—he didn’t want to throw her under the bus, as we would say today,” she told Electric Lit. “He knew he didn’t really know what the truth was, and he was also a man who had suffered terribly. He was like, ‘Well, maybe, maybe if we looked into it…’ and I found that to be such a human moment.”