As one of the formative voices of science fiction, H.G. Wells has been credited with predicting everything from the World Wide Web to the atomic bomb. In 1896, though, he published an uncharacteristically gruesome tale called The Island of Dr. Moreau—and forever changed the face of science fiction.

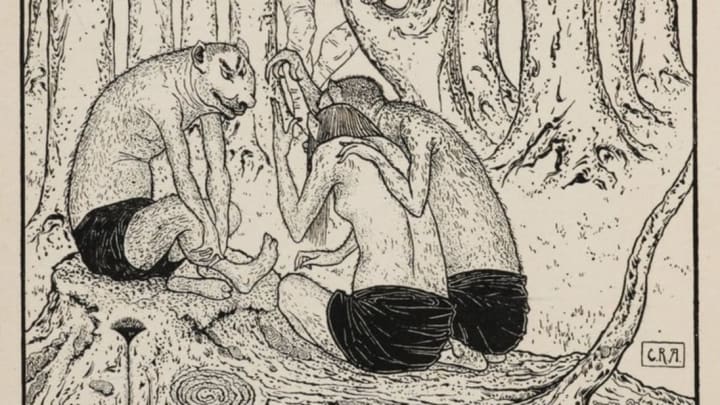

Sandwiched between 1895’s The Time Machine and 1897’s The Invisible Man, The Island of Dr. Moreau spun the tale of a shipwrecked Englishman stranded on an island where a scientist is performing breathtakingly cruel surgeries on animals, hoping to transform them into humans. While it wasn’t as well received as some of the author’s other “science romances,” the book has become an indelible part of our pop-culture landscape, inspiring multiple film adaptations, radio dramas, video game characters, and a “Treehouse of Horror” segment on The Simpsons (“The Island of Dr. Hibbert”). Here are seven curious facts about Wells’s most unsettling work, which turns 125 this year.

1. The Island of Dr. Moreau was inspired by an emotional debate over animal experimentation.

Wells was both a student and teacher of evolutionary biology, earning his Bachelor of Science degree in zoology just six years before The Island of Dr. Moreau was published. His tale of a scientist’s grotesque experiments to create human-animal hybrids was partly a response to public outcry over the practice of animal vivisection. It’s been suggested that Dr. Moreau was inspired by Scottish neurologist David Ferrier [PDF], the first scientist tried under the UK’s 1876 Cruelty to Animals Act for his experiments on the brains of dogs and monkeys.

2. Upon publication, The Island of Dr. Moreau was considered lurid and gratuitously violent.

With its references to vivisection and cannibalism, The Island of Dr. Moreau was shockingly graphic for its time. London’s Saturday Review criticized its “cheap horrors” and accused Wells of seeking out “revolting details with the zeal of a sanitary inspector probing a crowded graveyard.” The Daily Chronicle clutched its pearls even more dramatically, fearing the book might cause “real injury” should it fall “into the hands of a child or a nervous woman.” The Daily Telegraph simply called it “a morbid aberration of scientific curiosity.”

3. H.G. Wells didn’t think The Island of Doctor Moreau was particularly outlandish.

In an 1895 essay called “The Limits of Individual Plasticity,” Wells seems to have argued that results like the ones his fictional doctor would later achieve were not purely the stuff of imagination. He proposed that living subjects might be surgically and chemically “moulded and modified” into entirely different creatures. The essay goes in some bizarre directions, positing that scientists might one day be able to create living mermaids and other mythological beings.

4. The Island of Doctor Moreau popularized a major science-fiction trope.

The Island of Dr. Moreau is considered the first significant instance of a science-fiction convention known as “uplift,” where one species attempts to influence the development of another, often by nudging it up the evolutionary ladder. The device has since become one of the genre’s sturdiest tropes, appearing in titles ranging from Planet of the Apes and Guardians of the Galaxy to Futurama and Rick and Morty.

5. H.G. Wells wasn’t a fan of the movie version of The Island of Dr. Moreau.

In 1932, prolific B-movie director Erle C. Kenton didn’t exactly tone down the horror when he adapted Wells’s book for Paramount as Island of Lost Souls. In the U.S., the film was banned in 14 states for its embrace of evolutionary science, not to mention Dr. Moreau’s (Charles Laughton) supposedly blasphemous line “Do you know what it means to feel like God?”

In the UK, the film was barred from release three times between 1933 and 1957, partly because of its references to vivisection and partly, it’s been surmised, because of some implied hanky-panky between the film’s hero, Edward Parker (Richard Arlen), and a hybrid creation named Lota the Panther Woman (Kathleen Burke, who won the role in a nationwide talent search)—an element not present in the original book. The second time Paramount submitted the film to the British Board of Film Classification, the examiner called it “old and bad” and “a dated monstrosity.”

None of this bothered Wells in the least—he didn’t like the movie and was more than happy to see it kept out of theaters in his native England.

6. Adapting The Island of Doctor Moreau into a movie made director Richard Stanley have a breakdown.

Stanley, the talented filmmaker behind cult favorites Hardware and Dust Devil, was hired by New Line Cinema in 1994 to make his version of Wells’s novel. Even before filming began in Australia, the movie was beset by issues: stars dropped out; an assistant was bitten by a venomous spider; a member of Stanley’s team was unexpectedly hospitalized. Things didn’t ease up when production began, and the studio replaced Stanley just a few days in.

There was a fear he might cause trouble, so the studio had Stanley escorted to the airport to catch a plane back to LA. But instead of getting on the plane, the director somehow ditched his escort and returned to the filming location, where he hid in the jungle for several weeks, living on coconuts, yams, and cassava and smoking a prodigious amount of weed, before sneaking onto the set in a stolen dog-man costume and participating in the movie’s fiery, set-wrecking finale.

7. The Island of Dr. Moreau has inspired a diverse range of musical artists, from Diana Ross to Devo.

Devo’s 1978 debut album Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo! took its title from the Law, a call-and-response litany of prohibitions given to the island’s Beast Folk to keep them from reverting to animalistic behavior. Oingo Boingo also referenced the Law in their 1983 song “No Spill Blood,” and ’90s hip-hop trio House of Pain took their name from a line in the Law referring to Moreau’s laboratory (“His is the House of Pain”). In 1985, the video for Diana Ross’s “Eaten Alive” riffed on both The Island of Dr. Moreau and Island of Lost Souls with its depiction of Ross as a hybrid cat-woman pursuing a man who’s been stranded on a tropical island.