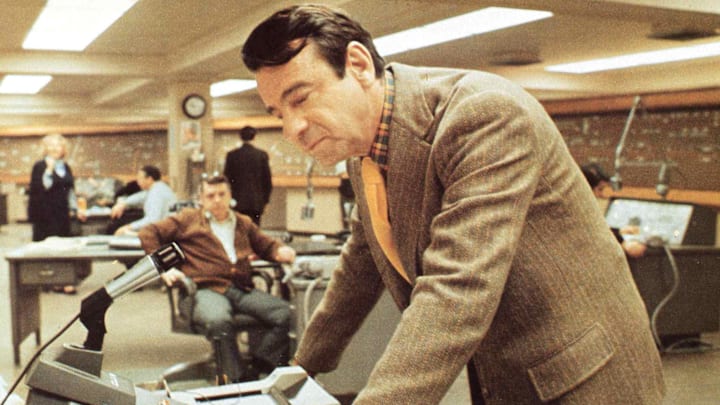

Make a list of the greatest movies ever set in New York City, the best 1970s crime films, or the most memorable movies set on trains, and all three should include The Taking of Pelham One Two Three. Directed by Joseph Sargent and featuring an ensemble cast that includes Walter Matthau, Robert Shaw, Martin Balsam, Jerry Stiller, and Héctor Elizondo, this story of a gang of four hijackers who hold a subway train for ransom has endured for five decades now as one of the finest films of its kind.

In honor of its 50th anniversary, we gathered a dozen facts about the making of the picture, from how its reluctant director dealt with tensions on the set to negotiations with New York’s transit authority. Let’s take a deep dive into the story of The Taking of Pelham One Two Three.

- The Taking of Pelham One Two Three takes liberties with its source material.

- Joseph Sargent didn’t want to direct The Taking of Pelham One Two Three.

- The crew of The Taking of Pelham One Two Three didn’t like the director.

- The MTA had problems with the story depicted in The Taking of Pelham One Two Three.

- One key feature of New York in the 1970s is missing from the film.

- The film’s visual style was inspired by the subway cars themselves.

- Innovative techniques were used to deal with the low light.

- The film used real New York locations.

- The subway tunnel was “hell on Earth.”

- The third rail wasn’t live, but it still made everyone nervous.

- For years, the departure time was banned on New York trains.

- There are two other versions of the story.

The Taking of Pelham One Two Three takes liberties with its source material.

Though best known today as a movie, The Taking of Pelham One Two Three wasn’t an original story for the screen. It’s an adaptation of the 1973 novel of the same name by John Godey (the pen name of author Morton Freedgood).

Both stories are about a group of thieves hijacking a subway train and demanding a ransom for hostages, but screenwriter Peter Stone took more than a few liberties with his version of events. Between the novel and film, characters live and die in different ways and the hijacking procedure happens in another way.

Most importantly, though, the character of Lt. Zachary Garber (Walter Matthau), the film’s main hero, is largely an invention of Stone’s script, a composite of certain transit police characters in the novel. Even after Matthau read and liked the screenplay, Stone kept adding new material for the character, beefing up his role to suit Matthau’s star power and presence in the film.

Joseph Sargent didn’t want to direct The Taking of Pelham One Two Three.

Joseph Sargent was already an experienced film and TV director whose credits included episodes of The Man From U.N.C.L.E. and The Fugitive, as well as movies like White Lightning. He felt like a natural fit for the gritty caper that was The Taking of Pelham One Two Three. Distributor United Artists certainly thought so and approached the director to make the film, but Sargent would later recall a reluctance to take on the project, feeling it was too similar to some of his other work.

“At the time I was dreadfully unhappy with the fact that I was going to be doing another, a caper movie, you know, a feature that U.A. wanted me to do,” he said in an interview with the Directors Guild of America (DGA). Sargent did ultimately take the job, only to be met with even more challenges once he arrived in New York to start production.

The crew of The Taking of Pelham One Two Three didn’t like the director.

When Sargent showed up in New York City to direct the film, he was greeted by producers Gabriel Katzka and Edgar J. Scherick, who weren’t too happy that United Artists had forced a director on them rather than allowing them to select their own. Things got worse when it came to the New York-based crew. Though Sargent was born in New Jersey to Italian immigrants, the crew thought the director had a West Coast vibe, which they didn’t like.

“It then moved from there and trickled down to the crew, which had resentment to this smart-ass director being sent from Hollywood to show them how to make movies,” Sargent told the DGA. “Then I began to realize that there was an East Coast, West Coast rivalry going on, which I had never imagined existed. I had no idea. It never came up before. Even after I reminded them that I was basically a New Yorker and that this was hometown for me, [it] didn’t matter. I was from Hollywood and I was quite obviously the enemy. Now, that’s a hell of [a] way to come into town to start a movie.”

Fortunately for Sargent, the film’s cast was much more receptive to his style and presence. “Thank god for the actors, because from Walter Matthau down, it was a joy,” he said.

The MTA had problems with the story depicted in The Taking of Pelham One Two Three.

Sargent and company wanted to shoot The Taking of Pelham One Two Three not just in New York, but with the cooperation of the city’s transit authority, who would hopefully provide the trains, tracks, and stations used in the film. Of course, because the story is about hijacking a subway train in their city, the transit officials were less than enthused about the idea that they were participating in a film that could inspire copycats. To combat this, the city insisted that the production take out a $20 million insurance policy with special coverage in the event of a hijacking and add a disclaimer to the credits, which stipulated that the transit authority offered no actual advice on the working features of their trains for the story.

For a little added insurance against people trying to copy the film, the script simplified elements of the novel’s hijacking procedure and even fictionalized elements of the heist, inventing a way for the hijackers to override a train’s “deadman’s switch,” to throw off any copycats.

“We’re making a movie, not a handbook on subway hijacking ... I must admit the seriousness of Pelham never occurred to me until we got the initial TA reaction,” Sargent told The Los Angeles Times in 1974. “They thought it [was] potentially a stimulant—not to hardened professional criminals like the ones in our movie, but to kooks. Cold professionals can see the absurdities of the plot right off, but kooks don’t reason it out ... we gladly gave in about the ‘deadman feature.’ Any responsible filmmaker would if he stumbled onto something that could spread into a new form of madness.”

One key feature of New York in the 1970s is missing from the film.

Aside from their issues with the story, the MTA also issued one other major demand to the production that greatly affected the film’s look: Any subway cars used in the movie had to be completely free of graffiti. This was New York City in the mid-1970s, so graffiti was everywhere. The filmmakers argued for authenticity, but the MTA refused to budge, so Sargent eventually gave in.

“New Yorkers are going to hoot when they see our spotless subway cars,” Sargent told The Los Angeles Times. “But the TA was adamant on that score. They said to show graffiti would be to glorify it. We argued that it was artistically expressive. But we got nowhere. They said the graffiti fad would be dead by the time the movie got out. I really doubt that.”

The film’s visual style was inspired by the subway cars themselves.

To shoot Pelham, Sargent turned to cinematographer Owen Roizman, who was best known for shooting The French Connection and The Exorcist for director William Friedkin. In planning out the film’s look, Roizman made a couple of very important decisions, including arguing with Sargent over just how wide the widescreen format of the picture should be. Sargent favored the standard 1.85:1 ratio, while Roizman argued for the 2.4:1 “anamorphic” widescreen for an even wider frame. His reason? After hanging out in New York City’s subways, he realized the cars themselves almost perfectly matched a 2.4:1 frame.

“At first, Joe and Edgar said no,” Roizman recalled in a 2009 interview with the International Cinematographers Guild. “In fact, they sounded incredulous. I explained why I thought it would be more interesting, and suggested that I shoot a couple of tests in anamorphic and 1.85:1 simultaneously with trains coming in and going out of a station, and with people on the train. I had a small crew and shot with available light. It was no contest when we screened the footage the next day! Everyone agreed that the anamorphic format was right for this film.”

Innovative techniques were used to deal with the low light.

Much of the action in The Taking of Pelham One Two Three unfolds in a dark subway tunnel, with few natural light sources and even fewer places to hide movie lights. To get around this, Roizman used a couple of crucial techniques. One was simple: He simply replaced the existing light bulbs in the train tunnel with brighter photography bulbs, and added a little brown tinting spray.

The other method was a little more innovative, especially for the time. “I had Movie Lab pre-flash the negative at 20 percent with an optical printer,” Roizman said. “That allowed me to record details in the shadows with very little light in the tunnel scenes. I had never done it before, but Vilmos Zsigmond (ASC) and other cinematographers were post-flashing film after they shot it. That was more risky, because if something went wrong, you lost a day’s work. There was an extra expense for pre-flashing, but Joe and Edgar were on my side.”

Roizman’s pre-flashing technique not only resulted in better detail in the original frames, but ensured that future high-definition versions of Pelham would come out crisp and detailed.

The film used real New York locations.

After battling with the MTA over graffiti and hijacking insurance, The Taking of Pelham One Two Three made use of several real New York locations with the help of then-mayor John Lindsay, who even intervened on the film’s behalf with the MTA. Apart from the train control center where most of Matthau’s scenes take place, nearly every location in the film is a real place in New York. That includes the mayor’s residence, Gracie Mansion.

The subway tunnel was “hell on Earth.”

Though the production did get authenticity and production value out of other locations, much of the hard work of shooting The Taking of Pelham One Two Three happened underground, on a decommissioned spur of subway tracks near the closed Court Street Station in Brooklyn. The abandoned nature of the tracks meant that the cast and crew had free rein to move as they pleased, but it also meant that conditions in the tunnel were often less than ideal, with Sargent later calling the site “hell on Earth” and dubbing the eight-week underground shoot the “most stressful experience” of his professional life.

Numerous factors made the tunnel shoot difficult, but for Sargent, the worst was the sheer amount of dirt and dust accumulated in the space, so thick that the crew had to take extra precautions.

“Every time we moved the train, for instance, there was 70 or 100 years worth of dust that raised up, and just wiped out your throat, and everybody was coughing,” he said. “We all had to wear surgical masks because there’s no way you could move around without kicking up all that soot and dust that's been down there for years. I’m amazed that all of us came out of it still alive.”

The Court Street station and tunnel were used in numerous other film productions over the years, and the site is now home to New York’s Transit Museum.

The third rail wasn’t live, but it still made everyone nervous.

One of the film’s crucial scenes, featuring the suicide of lead hijacker Mr. Blue (Robert Shaw), requires the character to touch the fabled third rail in the subway and electrocute himself. It’s an important scene that had to play on common fears, but that also meant the cast and crew had to be very careful about the actual third rail.

According to Sargent, the MTA not only made sure to shut down the third rail in areas where the production was filming, but also used heavy chain links secured to the rail itself which would short it out if anyone accidentally flipped the wrong switch in the control room.

“But you still got a little nervous, especially when Bob Shaw had to put his foot against it,” Sargent recalled. “And nobody ever tested the third rail until Bob actually had to touch it with his foot, and then it was double tested and double checked.”

For years, the departure time was banned on New York trains.

The Taking of Pelham One Two Three is so named because it follows a train that departs from Pelham at 1:23 p.m. When the film proved to be successful, the name went down in pop culture history, so much so that it actually made MTA employees a bit superstitious.

According to Jim Dwyer’s book Subway Lives: 24 Hours in the Life of the New York City Subway, the departure time of 1:23 a.m./p.m. was “unofficially banned” on all trains in New York for more than a decade. In 1987, a transit executive told schedulers that they should go ahead and start using the time again, but even then, schedulers would apparently go out of their way when planning train stops to avoid the 1:23 designation for any train.

There are two other versions of the story.

Though the original 1974 film remains the most beloved adaptation of Pelham One Two Three, there are actually two other adaptations of Godey’s novel out there. The least-known today is a 1998 made-for-TV movie, which aired on ABC starring Edward James Olmos as the lead cop on the case—this time named Anthony Piscotti—and Vincent D’Onofrio as Mr. Blue.

In 2009, the story was adapted yet again, this time by Top Gun and Man on Fire director Tony Scott. Starring Denzel Washington as a subway dispatcher named Walter Garber and John Travolta as Mr. Blue, the film was released by Sony Pictures and offered a slick, post-9/11 update to the story.

Additional Sources: Audio Commentary by Pat Healy and Jim Healy, The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (Kino Lorber Studio Classics, 2016); Subway Lives: 24 Hours in the Life of the New York City Subway by Jim Dwyer; Fun City Cinema: New York City and the Movies that Made It by Jason Bailey)

Discover More Fascinating Facts About ‘70s Crime Movies: