In 2003, the BBC aired Our Top Ten Treasures, a TV special highlighting 10 precious artifacts discovered in the UK. Naturally, the list went heavy on all that glitters: the Mold gold cape, the Sutton Hoo ship burial treasure, various hoards, etc.

But it also featured the Vindolanda tablets, a massive collection of documents unearthed at the site of what was once a key Roman fort in northern Britain. What the tablets lack in luster they more than make up for with a wealth of stunning detail about what life was like on Rome’s British frontier in its early days. Here are eight illuminating facts about them.

1. The Vindolanda tablets date back to early Roman Britain.

When Roman emperor Claudius invaded Britain in the 40s CE, he dispatched troops to establish forts across the territory—a practice that continued after his death in 54 CE. One such fort was known as Vindolanda, believed to have been constructed in 85 CE. It’s located in modern-day Northumberland and just south of Hadrian’s Wall, which Roman troops started building to mark and defend the empire’s northern border in 122 CE.

There were at least nine iterations of the Vindolanda fort constructed over the next 500 years or so. Occupants would demolish their fort before departing, and the following garrison would cover the site with clay and turf before raising a wholly new fort. Thanks to protection from those layers of sealant and the lack of oxygen deep underground, artifacts from the pre-Hadrianic Vindolanda forts—including the tablets—are remarkably well preserved.

2. The first tablet was discovered in 1973 …

Scholars have long known that Vindolanda harbors evidence of its ancient Roman history: British antiquarian William Camden mentioned so in his 1586 book Britannia, and plenty of others surveyed the site up through the mid-19th century. But modern scientific excavations didn’t really kick off until after archaeologist Eric Birley bought the land in 1929. His son, Robin Birley, eventually joined him in the research and later took over the entire project.

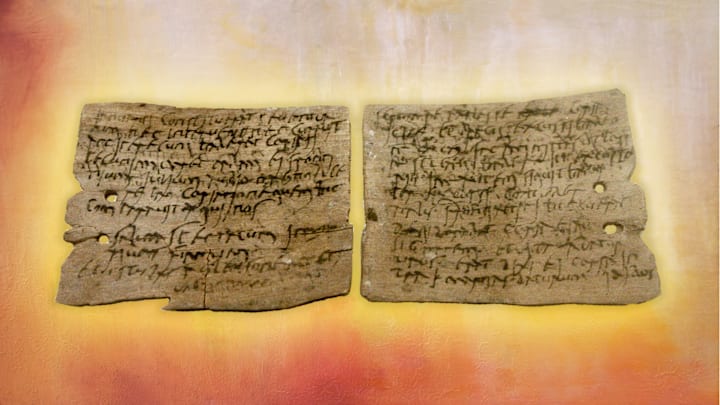

It was Robin Birley who unearthed the first Vindolanda tablet in March 1973: two thin, oily, incredibly fragile fragments of wood stuck together. Plenty of other wood had been found in this particular deposit, but nothing that bore a handwritten message. In fact, almost no handwritten messages from this early era of Roman Britain had ever been found.

“If I have to spend the rest of my life working in dirty, wet trenches, I doubt whether I shall ever again experience the shock and excitement I felt at my first glimpse of ink hieroglyphics on tiny scraps of wood,” Birley wrote.

3. … And hundreds more have been discovered since.

Through further excavation, Birley and his team uncovered some 200 more tablets—and the digging hasn’t stopped since. Archaeologists are actively recovering artifacts of all kinds (including one very notable toilet seat) from Vindolanda today; and the Vindolanda Trust, which sponsors the work, estimates that only about one-fourth of the site has been excavated. To date, the number of Vindolanda tablets totals more than 1800.

They no longer hold the title for Britain’s oldest handwritten documents: That now belongs to the Bloomberg tablets, 405 wooden plates discovered below a London office building in 2016. The oldest of those dates back to sometime between 43 and 53 CE. But the Vindolanda tablets are still the largest collection of handwritten documents from Roman Britain.

4. Many, but not all, of the tablets are written in ink.

Some of the Vindolanda tablets are of the variety most associated with ancient Rome: a thin slab of wood covered in wax, into which you’d impress your message using a metal stylus. Though the wax has typically worn away by the time modern-day archaeologists rediscover such items, you can sometimes still see the words etched in the wood where the stylus pressed too deep. This is the case with certain Vindolanda tablets.

But many others—including Birley’s first find—were written in ink made from carbon, gum arabic, and water. Though historians knew that ink tablets existed during this era, it wasn’t too common to actually find one, especially not in Britain. The sheer volume of those unearthed at Vindolanda in the 1970s were evidence that putting ink to wood was a regular practice in that area of Roman Britain at the time.

5. The first tablet confirmed that soldiers wore socks and underpants.

Birley’s inaugural Vindolanda tablet isn’t just notable for having been the first discovery. It also helped validate the long-held theory that soldiers sometimes donned socks and underwear—clothing items that didn’t get immortalized on monuments like other military garb did—in cold weather.

One (mostly) decipherable section of the message reads, “I have sent (?) you … pairs of socks from Sattua, two pairs of sandals and two pairs of underpants.” As Birley put it, “even if socks and underpants were not part of the soldier’s regular uniform, they were at least worn occasionally as additional clothing.”

6. One tablet features a birthday party invitation.

Officers were allowed to bring their families to live with them at the forts, and some of the tablets bear messages passed to and from officers’ wives. In one letter—often cited as the oldest handwriting by a woman in Britain—Claudia Severa invites her friend Sulpicia Lepidina to celebrate her birthday with her.

“Claudia Severa to her Lepidina greetings. On 11 September, sister, for the day of the celebration of my birthday, I give you a warm invitation to make sure that you come to us, to make the day more enjoyable for me by your arrival, if you are present,” she wrote. “Give my greetings to your [husband] Cerialis. My [husband] Aelius and little son send him (?) their greetings.”

7. And another reveals contempt for the native Britons.

Not many of the Vindolanda tablets discuss the region’s native Britons, but one note does refer to them as Brittunculi—a previously unknown term that meant something like “wretched Britons” or “wretched little Britons.” Clearly, the writer didn’t think much of them.

“The Britons are unprotected by armor (?). There are very many cavalry. The cavalry do not use swords nor do the wretched Britons mount in order to throw javelins,” it reads.

Due to the dearth of written material from Vindolanda regarding the Britons—and the fact that Brittunculi hasn’t shown up anywhere else—it’s tough to draw any conclusions about the general attitude toward them. The context of the note remains a mystery, too. It’s been suggested that the Romans may have been gathering intel either to protect their own troops against the Britons or to determine whether the Britons might be viable recruits.

8. The tablets suggest that Latin was the Roman army’s lingua franca.

It’s noteworthy that the tablets’ messages were written in Latin, because most of the soldiers posted at Vindolanda weren’t Roman: They were auxiliary troops, which the empire enlisted from other territories and paid less with a guarantee that they’d be granted Roman citizenship after 25 years of service. During its pre-Hadrianic period, Vindolanda played host to troops from modern-day Belgium, the Netherlands, and northern Spain.

“You’re dealing with lots of people who come from different backgrounds, and they have to be able to communicate with each other,” archaeologist Andrew Birley, Robin’s son and the current director of excavations at Vindolanda, told National Geographic. And since the tablets feature everything from salary information to supply lists, it seems that keeping meticulous records—and, by default, being literate enough in Latin to do so—was an expectation in the Roman army.

It wasn’t just members of the military (and their families) who communicated in Latin: Enslaved people did, too. In one letter, an enslaved man named Severus writes to another named Candidus regarding provisions for Saturnalia, a Roman pagan festival celebrated in December: “ … for the Saturnalia, I ask you, brother, to see to them at a price of 4 or six asses and radishes to the value of not less than 1/2 denarius.” (Asses were copper coins; and each silver denarius was worth 10 asses.)