Some of us are thinking daily about the Roman Empire—but are we really clear on the facts versus fiction? Let’s travel back to the time of togas to get to the bottom of some prevalent misconceptions about the era, adapted from an episode of Misconceptions on YouTube.

1. Misconception: Caligula’s horse held public office.

In the 1976 BBC miniseries I, Claudius, Emperor Caligula greets his horse, Incitatus, at a wedding reception. “He’s never been to a wedding before,” Caligula tells the other guests. “His life has really opened up since I made him a Senator.”

Appointing his horse to public office has long been cited as a prime example of just how deranged Caligula was. But did he really give Incitatus a seat in the government?

Caligula’s reign lasted all of four years and was characterized by so much corruption and cruelty that people thought he suffered from insanity. Officials put a stop to the tyranny by assassinating him in 41 CE. In other words, Caligula was unpredictable enough that it wouldn’t be surprising if he did give his horse a government position.

Robert Graves’s 1934 novel I, Claudius alleged that Caligula not only made Incitatus a senator, but that he planned to nominate him for Consul—the highest political rank. Graves likely got this idea from earlier historical works. In the The Lives of the Twelve Caesars, published in 121 CE, the historian Suetonius punctuates a description of Caligula’s love for Incitatus by stating, “It is even said that he intended to make him Consul.”

Suetonius doesn’t specify who said it, and modern scholars agree that Caligula probably never followed through on this plan, if it ever was a plan. According to historian Mary Beard, it’s possible that Caligula proposed it as a joke. Aloys Winterling, the author of Caligula: A Biography, thinks it could have been the emperor’s way of mocking his fellow politicians:

“To destine [the emperor’s horse] for the consulship satirized the main aim of aristocrats’ lives and laid it open to ridicule. Caligula placed his horse on the same level as the highest-ranking members of society—and by implication equated them with a horse.”

Even if Incitatus was never meant to be Consul, he did live like one. Caligula supposedly kept him in a marble stable, dressed him in jewels and fine fabrics, and gave him an entourage of servants to wait on him hand and foot. Or hoof and … hoof.

2. Misconception: Vomitoriums were rooms where Romans vomited so they could keep feasting.

Since the suffix -orium denotes a place and vomit means, well, “vomit,” the word vomitorium seemingly speaks for itself. But while vomitoriums did exist in ancient Rome, they weren’t chambers where gluttonous revelers could empty their stomachs to make room for more food.

The earliest known mention of a vomitorium comes from Saturnalia, written by Macrobius in the 5th century. It’s possible that Macrobius actually made the word up. Romans already knew the Latin verb vomĕre, meaning “to vomit,” and its corresponding adjective vomitus. And according to University of Iowa associate professor Sarah Bond, Roman writers were known to slap -orium onto the end of an existing word to name a new place.

In Macrobius’s case, the newly christened place in question was an amphitheater passage. These halls gushed large hordes of people into their theater seats and then back out to the streets so quickly that it seemed like the crowds were practically being vomited through the doorways. Macrobius was being metaphorical, but later audiences interpreted the word literally.

In his 1871 book Walks of Rome, August Hare called vomitoriums “a disgusting memorial of Roman imperial life ... whither the feasters retired to tickle their throats with feathers, and come back with renewed appetite to the banquet.” Other writers regurgitated similar descriptions through the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Aldous Huxley mentioned vomitoriums in his 1923 novel Antic Hay, and historian Lewis Mumford discussed the custom in his National Book Award winner, The City in History, published in 1961.

This rather revolting mix-up might have been easy to swallow because upper-class ancient Romans already had a reputation for feasting ad nauseam. As Seneca wrote circa 42 CE, “They vomit that they may eat, they eat that they may vomit.” Seneca was famously against excess of all kinds, so he may have been exaggerating for dramatic effect. But since wine flowed freely at every banquet, some party-goers probably did puke on occasion.

3. Misconception: Romans constantly wore togas.

Romans did wear togas, and they also promoted themselves as a toga-wearing civilization in art and literature. In Virgil’s Aeneid, he even describes Romans as “the race that wears the toga.” But it wasn’t the go-to garment for everyone, and certainly not all the time.

For one, generally only Roman citizens were allowed to wear them, so they were off-limits to conquered peoples, expats, and whoever else set foot on Roman soil. And though kids, women, and lower-class men did wear short togas early on in Roman history, the toga became more and more of a status symbol as time progressed.

At the height of imperial Rome, a toga cloth could be nearly 20 feet long, so it wasn’t cheap, and putting it on usually took the help of another person—say, a servant. And if you’ve ever fashioned a makeshift toga out of a bedsheet for a college toga party, you know what it’s like to try to move around in one: not easy. In other words, togas were most common among rich men who didn’t have to do any manual labor. People mainly donned them for important ceremonies and other public appearances, and otherwise stuck to tunics and poncho-esque apparel.

As University of Cambridge classic professor Caroline Vout puts it, “If we asked, ‘What do the Scottish wear?’ the answer would be ‘the kilt.’ But we would not expect to go to Edinburgh and find all but foreign tourists clad in plaid.”

4. Misconception: Julius Caesar’s last words were “Et tu, Brute?”

Thanks to Shakespeare, everyone remembers what Julius Caesar said as he succumbed to his stab wounds on the Senate floor: “Et tu, Brute?,” Latin for “And you, Brutus?” But this almost certainly wasn’t Caesar’s final utterance. It isn’t even Caesar’s final line before he dies in in the play—after that, he says “Then fall, Caesar!”

In real life, Julius Caesar may have said nothing at all. In Suetonius’s The Life of Julius Caesar, he wrote: “[Caesar] was stabbed with three and 20 wounds, uttering not a word, but merely a groan at the first stroke, though some have written that when Marcus Brutus rushed at him, he said in Greek, ‘You too, my child?’”

It wouldn’t have been unusual for a Roman to occasionally speak Greek at the time—it’s been called “a sort of universal language even among non-Greeks” of the era. Shakespeare may have chosen Latin for any number of reasons, but it’s not just the language that may mislead audiences about the true nature of Caesar’s assassination.

In the context of the play, “Et tu, Brute?” suggests that Caesar can’t believe his closest friend was in on the murder plot. But according to modern historians, Brutus was by no means Caesar’s closest friend—that was Decimus, whom Shakespeare only mentions as a side character named Decius. Decimus was sort of Caesar’s right-hand man during his reign, whereas Brutus had opposed him in the past. In the civil war from 49 to 45 BCE, for example, Brutus actually fought for Caesar’s adversary, Pompey. Of course, in the context of the play, it makes good dramatic sense.

So why would Caesar have spoken directly to Brutus as he bled out? The operative word in his purported question might have been child. Caesar could have simply been surprised that he was betrayed not just by the old-timers, but by his younger cohorts, too.

Kathryn Tempest lays out a different theory in her biography of Brutus, drawing on the work of James Russell, who analyzed curse tablets leading to a different understanding of the supposed Greek utterance, Kai su, teknon. “And you, too, child?” is one understanding of that phrase, but it’s also the beginning of a Greek proverb that means something like “you, too, will have a bite of my power.” Some have taken the phrase to be more of a curse than a heartfelt expression of betrayal, something along the lines of “back atcha!” or even “see you in hell!” And any of those interpretations are predicated on the belief that Caesar even said the Greek phrase at all, and that it wasn’t made up somewhere along the line to add a dramatic flourish.

History can be messy, but you can be confident that “Et tu, Brute?” wasn’t Julius Caesar’s final question.

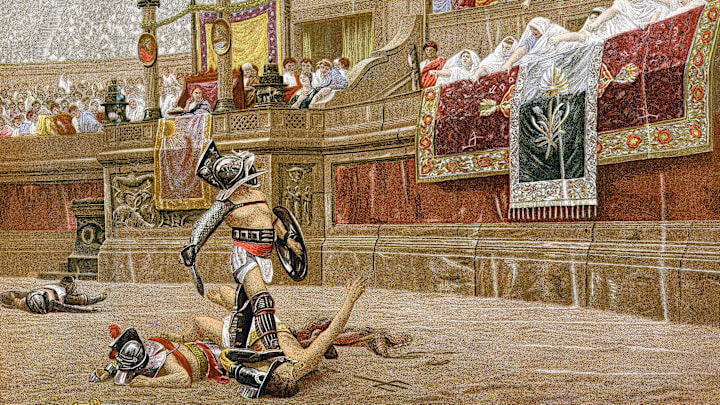

5. Misconception: Gladiators always fought to the death.

Hollywood epics like Russell Crowe’s Gladiator have given us a skewed view of Colosseum combats in more ways than one. Early fights did often involve enslaved or conquered people convicted of crimes, but the sport soon attracted voluntary combatants. By the 1st century, many showdowns were between career gladiators, usually former soldiers or poor citizens looking for a lucrative, if dangerous, opportunity. A large group of gladiators would train in a school called a ludus. There were even labor unions that organized funerals and offered financial support to the families of fallen combatants. Basically, being a gladiator was a full-fledged profession—albeit an extremely dangerous one.

But it wasn’t always a duel to the death. Since we don’t have any comprehensive records of the fights, historians have relied on tombstone inscriptions and graffiti to estimate how many people perished in the arena. According to certain graffiti found in Pompeii, a set of 23 fights resulted in eight gladiator deaths. Not an advisable career path, but not exactly the Thunderdome, either. Nineteenth-century historian Georges Ville compiled stats from 32 fights from the first century and found that only six gladiators died—that’s about a 90-percent chance of survival for that particular pool of combatants. Your odds went down the more often you fought, of course, and tombstones reveal that many gladiators only made it to their early twenties.

There was financial incentive to prevent every bout from ending in death. Training and funding elite athletes was (and is) a costly endeavor, and sponsors would have had serious cash flow issues if they constantly had to replace their charges. Often, the referee would call the fight when one participant was wounded.

6. Misconception: Nero fiddled while Rome burned.

In the summer of 64 CE, a terrible fire began near Rome’s chariot-racing stadium, the Circus Maximus. High, dry winds carried it through 10 of the city’s 14 districts over several days. As the blaze leveled whole sections of Rome, Emperor Nero was supposedly watching from a palace tower. And he was playing the fiddle.

This is impossible for two simple reasons. One: Nero was about 35 miles away, safe at his villa in Antium for much of the fire. Two: Fiddles weren’t invented until the Middle Ages. Now, Nero was skilled at playing other stringed instruments, like the kithara, which is sort of a cross between a handheld harp and a small guitar. Skilled might be generous for describing his musical abilities—Suetonius says that, supposedly, his singing was so bad people would fake their death to be able to leave his performances. And several ancient Roman historians claim he did launch into some kind of performance during the Great Fire. In 109 CE, Tacitus wrote that Nero “appeared on a private stage and sang of the destruction of Troy, comparing present misfortunes with the calamities of antiquity.” About a century later, Cassius Dio alleged that Nero was wearing “lyre-player’s garb” while staging his solo ode to Troy.

So is calling the widely spread story a “misconception” just a case of pedantic semantics? While it’s true that Nero was criticized for his response to the fire—some Romans actually thought he had purposely set it, himself, because he wanted to rebuild his palace to look more modern—it’s also misleading to say that he dithered away any opportunity to respond to the disaster.

The cause of the fire remains a mystery, but the emperor did oversee some relief efforts. Nero returned to Rome and let people take refuge in his private gardens and the city’s remaining public buildings. He also slashed the price of grain and had food shipped in from the surrounding areas. According to Tacitus, these gestures didn’t improve his reputation, since the rumor about his one-man show had spread nearly as fast as the fire.