On May 12, 1862, Robert Smalls escaped enslavement with an ingenious plan. As a ship’s pilot who helped vessels navigate in and around South Carolina’s Charleston Harbor, Smalls was working on a Confederate transportation ship called the Planter. After the white crewmembers had gone ashore for the night, Smalls convinced the other enslaved men in the crew to turn the ship around, quietly pick up their family members waiting in the darkness on shore, and sail past the Confederate barricades of Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie. “Smalls knew the proper signals to give, and even donned a captain’s hat to help disguise his identity as they steamed past the unsuspecting rebels,” the National Park Service writes. They managed to reach the Union’s naval blockade and gain their freedom.

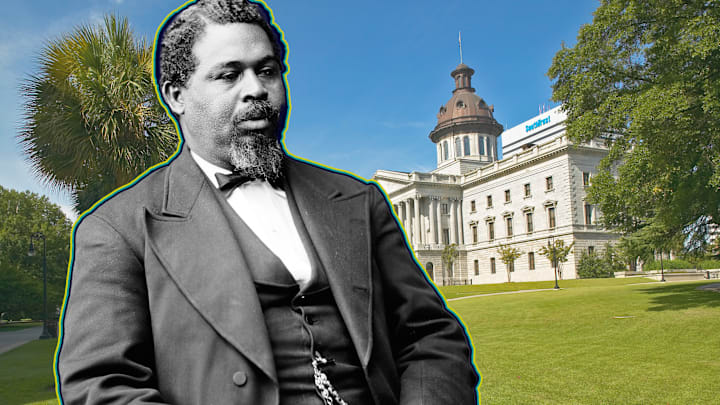

Now, more than 150 years later, South Carolina will create a statue commemorating Smalls for the State House in Columbia—the first dedicated to an individual Black South Carolinian to be placed on the grounds (there is a large monument dedicated to the state’s African American history already on display). Set to be completed by 2028, Smalls’s statue will join other monuments memorializing exclusively white historical figures, including George Washington, Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Confederate General Robert E. Lee, and former U.S. Secretary of State James Francis Byrnes.

Escape By Sea

Born in 1839 in Beaufort, South Carolina, Smalls spent his early years working alongside his mother in the plantation house of their enslaver, Henry McKee, before being sent to work as a waiter in a Charleston hotel when he was 12 years old. Hotel work led Smalls to the city’s docks, which in turn positioned him on the Planter when the Civil War broke out in 1861.

After gaining his freedom, Smalls turned the Planter over to the United States Navy and earned a bounty for having captured an enemy ship. He also offered the Union his services as a mariner and took part in several naval battles against Confederate forces around Charleston before being promoted to the rank of captain and given the command of the Planter itself.

In the years following the Confederacy’s collapse, Smalls used his reputation as a war hero to become involved in politics, organizing boycotts against the segregation of Philadelphia’s transit system and serving as a delegate to the Republican National Convention. In 1868, he was elected to South Carolina’s House of Representatives, and then to the United States Congress in 1874, where he fought for the rights of Black citizens. He even used his considerable wealth to buy the mansion of his former enslaver.

Honoring History

The long-awaited statue of Smalls corrects some of the shortcomings of the Reconstruction era, when former Confederates—pardoned for their actions by Abraham Lincoln’s successor Andrew Johnson—used their newly restored influence to replace slavery with segregation. Jim Crow laws and policies undid the promise of the Thirteenth Amendment and, by extension, erased the achievements of Smalls and countless others. Now, with the construction of his statue, part of that legacy will be restored.

“[Smalls is] someone that all South Carolinians can and should respect,” Chip Campsen, a Republican state senator, said at a recent commission meeting regarding the statue, according to Smithsonian. “He had a lot that he could be bitter about, but he [was] not. He set a course for the remainder of his life to try to make South Carolina a better place for all people of all races.”

Read More Amazing Stories in American History: