Erik Jan Hanussen looked out at the sea of bewildered, startled faces and knew he had them. It was the mid-1920s, and Hanussen was playing to sold-out audiences in Berlin, where curious crowds would assemble to see if his reputation as one of the world’s foremost mentalists was warranted.

Hanussen pointed to a woman in the crowd and told her she had a broken mirror in her pocketbook. Then he recited her home address. The lady gasped and nodded. He was undeniably accurate on both counts.

It helped that a co-conspirator collecting tickets for the show had peered into the woman’s purse, and seen the mirror; it was also useful to compare the number on her ticket to a logbook that a local hotel had used for the addresses of attendees. The methods were practical, but Hanussen's theatrical flair transformed them into something sensational. He was a showman, a onetime carnival boy who learned hypnosis and psychic parlor games that would eventually make him the toast of Berlin.

But Hanussen wasn’t content with wealth and fame. Sensing the rising influence of the Nazi party, the mentalist ingratiated himself into the Reich by befriending storm troopers and eventually finding a seat as a confidant of Adolf Hitler himself. In a divided Berlin, Hanussen's powerful friends could assure his safety. His ego told him he could manipulate them as easily as he did the civilians who marveled at his stage presence.

But Hanussen’s plan had one fatal flaw: He was not of Danish ancestry, as he claimed, but Jewish. Once that was uncovered, no sleight of hand would be able to keep him from the wrath of the dangerous men he foolishly thought he could control.

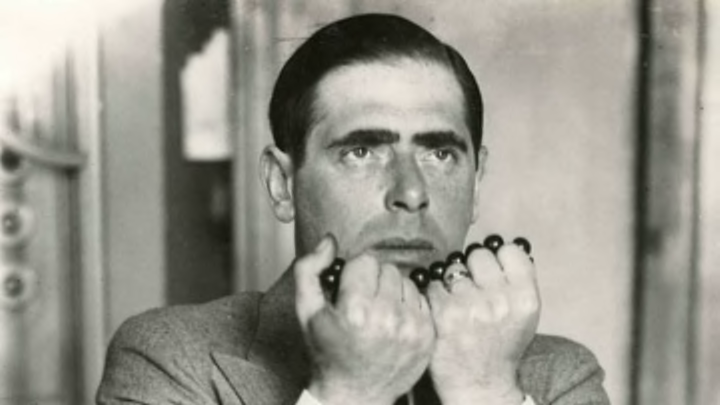

Hanussen hosting a seance. GruselTour-Leipzig

The son of poverty-stricken parents, Hanussen was born Hermann Steinschneider in Vienna, Austria, in 1889. His youth was chronicled in an autobiography he would publish in 1930, a point where his legend had long overtaken any objective history. To hear Hanussen tell it, he displayed early signs of clairvoyance during his childhood, with a restless nature pushing him into the circus as a teenager. At 14, he supposedly captured the heart of a 45-year-old woman and ran off with her before heading for Turkey and convincing sailors he was an opera singer.

Hanussen decided to change his name during World War I, when he began entertaining small theaters in Vienna and wanted to avoid being labeled a deserter. Throughout the war, he had impressed his fellow soldiers by steaming open letters, reading confidential information, then re-sealing the envelopes and announcing his mental powers had brought news from home.

By the 1920s, Hanussen had migrated to Berlin, a then-bustling metropolis that embraced psychic performances. Hanussen’s shows combined mentalism, mind-reading, and feats like finding objects hidden in theaters while blindfolded. Though some observers criticized Hanussen for being a fraud, they were usually drowned out by spectators, who came in droves to see his tricks.

Because Hanussen insisted he was the genuine article, he left himself open to the occasional legal challenge. When he visited the Czech Republic in 1928, he was arrested for defrauding the public out of funds. It took nearly two years for courts to decide Hanussen was something approaching a legitimate seer, a ruling that came after he performed for the presiding—and gullible—judge.

Back in Berlin, Hanussen’s Danish cover and great wealth were looked upon favorably by the Reich, who had been involved in a struggle for political power that was reaching a boiling point. Hanussen entertained Nazi officers on his private boat, in limousines, and at his palatial apartment. Through a weekly newsletter he published, Hanussen had flattered the regime with predictions of Hitler’s rise to power and extolled the virtues of a Nazi-led higher office. “The stars tell us Hitler’s days are coming up,” read one headline.

The Nazis had other reasons to favor Hanussen: They liked gambling, and they were often in debt. One officer, Count Wolf-Heinrich Graf von Helldorf, was named on several IOUs held by Hanussen, who had loaned the head of the storm troopers a considerable sum to cover his gambling losses. In doing so, Hanussen felt he could grease the wheels with Helldorf in the event Berlin was consumed by either the Jewish-loathing Nazi party or the communist opposition that incited violence.

Hanussen’s sympathies found favor at the very top of the Reich. At the height of his fame in the 1920s, he met Hitler in the restaurant at the Hotel Kaiserhof, where the Führer had taken up residence. With his Jewish name abandoned and his officer friends endorsing him, Hanussen had no reason to arouse any suspicions. By some accounts, he conferred with Hitler a dozen times between 1932 and 1933, evaluating the bumps on his head, reading his palms, and reassuring the dictator that his rise to power was inevitable. When in-person meetings were difficult, the two spoke on the phone.

In his mind, Hanussen may have believed his charm could eventually get Hitler to see another side of the Jewish faith—one that could aid him in his pursuits. It would prove to be a poor prediction.

Amazon

As Hanussen continued to perform both publicly and privately, he found himself under fire from local newspaper commentators who shared the Czech concern that he was defrauding the public. One paper published the accusation that he was not Danish, but Jewish. A rattled Hanussen tried to reframe the narrative and insisted he had merely been adopted by Jewish parents.

It was too late. The charge was discovered by Nazi officials, who now had every reason to doubt Hanussen’s blood. It was ambiguous enough that he wasn’t ostracized immediately, but the small talk among officers was grave: They were in debt to a Jewish man.

Hanussen dug himself in deeper following the fire at Reichstag in February 1933. The blaze, which consumed Nazi territory, was said to be the work of Communists. The day before, Hanussen had hinted of “a great blaze” that would dramatically impact the area. It was theorized that he had gotten word of the arson—which was never solved—from Helldorf, who might have known of plans for the Germans to set the fire and frame Nazi opposition in order to obtain complete control over civil liberties. It also meant Hanussen couldn’t be trusted with any confidential information.

On March 24, 1933, Hanussen was late for a performance. As stagehands scrambled to find him, he was hustled from his apartment by storm troopers and shaken down for his IOUs. Once they had been retrieved, officers shot him three times and left his body in a forest, where it was discovered by lumberjacks. He was 43.

Hanussen had tried to co-opt the rising Nazi power for his own purposes. It was a fool’s errand, and one he tried to insure by believing the Nazis could overlook his heritage because he offered financial favors. Before his death, Hanussen had written to a friend that he considered their Jewish persecution to be an “election trick.” For his critics, it was one final bit of proof that he certainly couldn’t read minds.

Additional Sources: The Nazi Séance: The Strange Story of the Jewish Psychic in Hitler’s Circle