by Michael Ridgeway

At 1,456 pages, War and Peace makes a big impression … and a great doorstop. But books don’t have to weigh a lot to be heavy hitters. Here are seven tiny tomes—all fewer than 100 pages—that sparked revolutions.

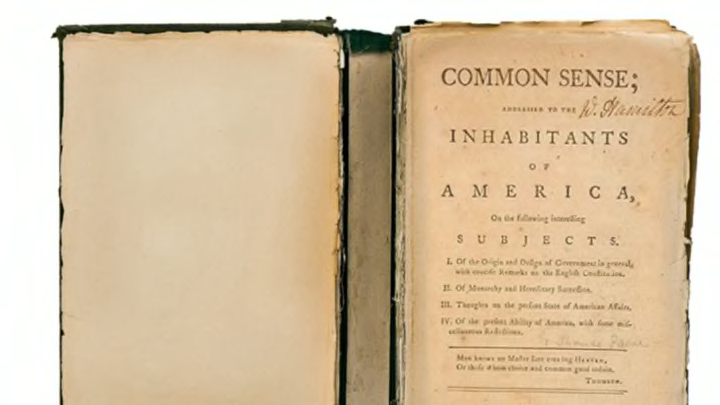

1. Common Sense by Thomas Paine (52 pages)

In the 1770s, American colonists were riding the fence. Should they cut ties with the tax-happy King George or just sit around drinking English tea? As they waffled, a penniless Brit named Thomas Paine sailed to Philadelphia and published the incendiary tract Common Sense.

Released in 1776, Paine’s text lambasted King George as a “crowned ruffian” and the progeny of a “French bastard.” The language struck a nerve, turning loyalists into patriots and nudging the likes of George Washington and John Adams into action. Less than six months later, the colonies declared independence, and the Revolutionary War was on. As for Paine, he went on to write another powerful little book, The Age of Reason, a deist work that criticized organized religion and questioned the authenticity of the Bible. This time, however, Paine’s words missed the mark. He was condemned as an atheist, shunned by friends, and denied citizenship in the United States—the young nation he helped create.

2. The Cat in the Hat by Dr. Seuss (72 pages)

Written in 1957 for children learning to read, The Cat in the Hat has saved generations of first-graders from the mind-numbing adventures of Dick and Jane. Instead of seeing Dick run and Jane pet Spot, kids got to watch as a free-spirited, umbrella-toting cat stood on a ball, juggled goldfish, and generally encouraged chaos. Dr. Seuss spent a year and a half working on The Cat in the Hat; apparently, it’s not so easy to write a rollicking good tale with a vocabulary of only 236 words. Incredibly, just 15 words in the book are more than one syllable long.

3. The Prince by Niccolò Machiavelli (82 pages)

A how-to manual for aspiring dictators, The Prince is one of the most reviled, and most studied, political treatises in history. First published in 1532, the book gave rise to the idea that a ruler’s first duty is to build a strong and stable state, no matter what the cost. The Prince inspired numerous tyrants, including Oliver Cromwell, Hitler, and Mussolini. Stalin was particularly moved by the book, scribbling copious notes in the margins of his copy.

4. Civil Disobedience by Henry David Thoreau (26 pages)

If Machiavelli helped unleash tyranny on the world, then Thoreau taught the world how to fight back. His ideas were simple but revolutionary: Don’t obey evil laws, and don’t pay taxes to the governments that create them. Thoreau penned the essay collection in 1849, inspired by his disgust over issues such as slavery and the Mexican-American War. But few paid attention to Civil Disobedience during Thoreau’s lifetime. That wouldn’t happen until six decades later, when Gandhi came across the work while studying at Oxford and took a copy with him to South Africa. There, he and his followers used Thoreau’s ideas to launch a campaign of passive resistance against the government, later repeating those tactics in India. Civil Disobedience has been on the march ever since, toppling colonialism, segregation, apartheid, and all manner of injustice.

5. The Elements of Style by William Strunk Jr. and E.B. White (52 pages)

For nearly a century, this pithy little grammar book has taught Americans how to write. Along the way, it’s won over the hearts and minds of countless English teachers, copyeditors, and authors, from Dorothy Parker to Stephen King. First published by Strunk in 1918, the manual took on a new life in 1959 when author E.B. White was brought on board to revise and expand it. (The co-authored version exceeded 100 pages.) But the book’s key lessons have always remained the same: encouraging writers to be clear, use concrete language, and omit needless words. Surprisingly, the little rulebook has also inspired other forms of expression, including a ballet of the same name by choreographer Matthew Nash. Not everyone agreed with Nash’s interpretation, though. One reviewer panned the choreography as too indecisive, claiming it failed to distinguish between the active and passive voice.

6. The Art of War by Sun Tzu (68 pages)

Despite the title’s promise, most of this ancient Chinese handbook is about how to win a conflict without needing to fight. Sun Tzu was a military general 2,500 years ago, but he was also a Taoist philosopher who believed in getting to know your enemy and cultivating a peaceful state of mind. For this reason, The Art of War is studied not only by military strategists, but also by business executives, diplomats, and lawyers. The list of people influenced by the book is impressive: Napoleon, Chairman Mao, Donald Trump, and of course, Gordon Gekko, Michael Douglas’ character in 1987’s Wall Street, who quotes Sun Tzu continuously throughout the movie.

7. Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (54 pages)

Europe’s emerging communist movement was getting no respect in the mid-1800s, so it asked two good friends, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, to do what communists do best—write propaganda. The resulting manifesto recast history as one giant class struggle and outlined a 10-point program for building a communist state. The booklet climaxed with the rousing motto, “Workers of the world, unite!” About 40 years later, those words stirred the heart of young Vladimir Lenin, who led the Bolshevik Revolution and helped create the Soviet Union. What followed was a series of unfortunate events, including the nuclear arms race, the Vietnam War, and, of course, Rocky IV.

Want more amazing stories like this? Subscribe to mental_floss magazine today!