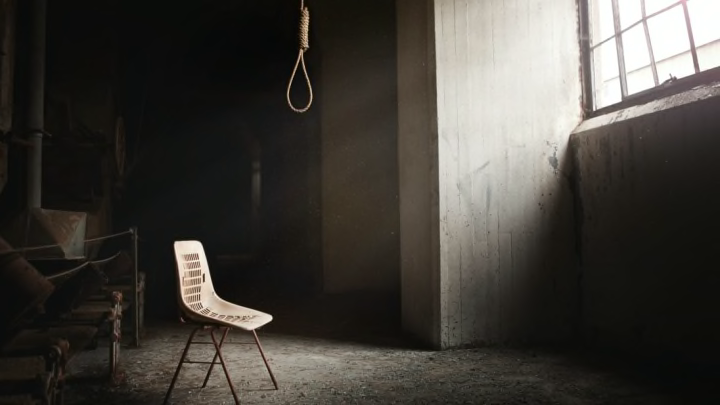

Hanging is a pretty simple way to kill someone. All you really need is a length of rope, someone who can tie a decent knot, and something from which to hang the victim. If you're having a fancier execution, you can dress things up with gallows and use the victim’s height and weight to figure out how much slack the rope needs to kill them, but not take their head clean off—a common occurrence until British hangman William Marwood developed the “long drop” in 1872. It’s no-nonsense and versatile. Hanging has been a favored method of execution for everyone from lynch mobs to governments since at least the fifth century (edit: BCE)(when the Persian noble Haman was hanged in the Bible’s Book of Esther).

Here’s the thing, though. For as long as we’ve been using it, we don't know what makes hanging work so well.

Sure, we have a general idea of what’s going on. Suspension hanging and short drops strangle the victim, and standard drops and long drops break the neck. Medically speaking, though, that’s a little vague. We don’t always know what specifically is happening to the neck when it comes to a sudden stop at the end of a noose.

Rarely does it even appear to be the same thing from person to person. With some longer drops, one or more of the cervical vertebrae is severely fractured. With others, they’re barely damaged. Sometimes the spinal cord or the vertebral arteries are crushed and sometimes they aren’t. With some shorter, strangling drops, the airway is closed or crushed. Sometimes it’s spared, but pressure on the carotid artery causes an arterial spasm, starving the brain of blood.

Suddenly, hanging doesn’t seem so simple anymore.

Fortunately for the morbidly curious, a number of scientists have embraced the grim job of studying hanging, some even going so far as to experiment on themselves. A group of researchers formed The Working Group on Human Asphyxiation (WGHA) in 2006, and have since reviewed historical and medical texts (the best stuff comes from between 1870 and 1930, when hanging was very in vogue in the U.S. and Europe), looked at the data from animal experiments, and even analyzed filmed human hangings, all in an effort to get to the bottom of what makes hanging so effective.

A little gruesome? Sure, but the WGHA doesn’t have anything on Nicolas Minovici. For his 238-page “Studies on Hanging” (1905), the Romanian forensic scientist analyzed 172 hanging suicides and executions and then, to really get a feel for it, hanged himself.

Then he did it 11 more times.

At first, Minovici took a few practice runs with a non-contracting noose to “get used to” the sensation of staring down death. Then he went for the real deal—12 rounds with a regular contracting noose that left him dangling several feet off the ground. While he was apologetic that he “could not take the experiment any longer than three to four seconds,” Minovici’s study did make one big leap in the science of hanging. His self-experimentation revealed that a person who is hanged usually loses consciousness not because of strangling but from disrupted bloodflow. Minovici also studied tattooing among Romanian citizens and convicts. No word on whether he got some prison ink of his own as part of it.