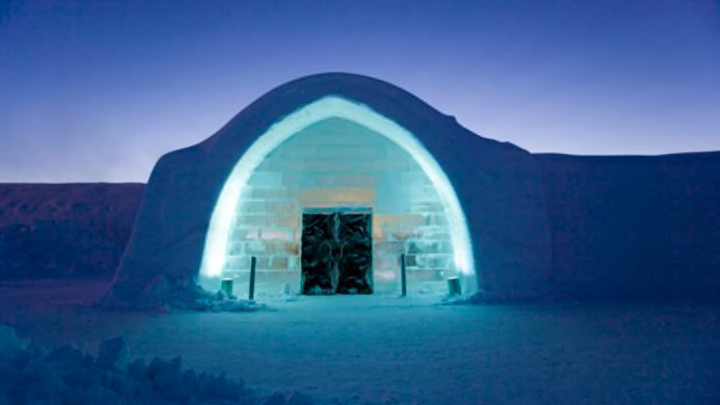

In the tiny arctic village of Jukkasjärvi, Sweden, dusk lasts most of the day at this time of year. Against the dramatic and ever-evolving pink and purple sky sits a structure that looks like a cross between a sleek nightclub and an igloo from outer space: Lapland’s storied IceHotel, the world’s largest and longest-running luxury hotel made entirely of frozen water.

A sprawling single-story structure built annually on the pristine banks of the frozen Torne River, the IceHotel is in its 23rd incarnation. In the late '80s, Yngve Bergqvist, who led white-water rafting trips on the Torne during the long arctic summers, invited some ice sculptors to create a winter river attraction. The result was an ice art gallery—a small igloo on the frozen river in which art work could be displayed. After a couple of years, an adventurous group asked if they could spend the night in the igloo. Afterward, they raved so much about the experience that Bergqvist decided to build a proper hotel. The first IceHotel was erected in the winter of 1989-1990. These days, it attracts 60,000 guests who want to spend a night in one of its 65 rooms. Of these, 15 are one-of-a-kind “art suites”—among this year’s are a UFO-themed room and a fairytale forest—designed and sculpted by visiting artists from all over the world.

Staying in the hotel is kind of like camping out in a meat locker. The inside temperature is a constant 23 degrees Fahrenheit. Even the bedframes are carved ice—but a mattress, a reindeer pelt, and a sleeping bag make sleeping quite cozy. In the lobby’s Ice Bar, patrons huddle in heavy parkas, thick mittens, and snow pants. With the exception of a few cushions, every surface is gleaming ice—including the glasses in which the cocktails are served.

The hotel betrays a minimalist aesthetic that’s a hallmark of Scandinavian design. And the frozen architecture lends a serene quality even when the lobby is crawling with tourists. But when I visited on an impossibly clear and cold week this winter, the most remarkable thing about the place was going on behind the scenes: Amid the hustle and bustle, the IceHotel team was already quietly at work on the assiduous process of building next year’s hotel. It takes 1000 tons of crystal-clear ice cut straight from the river and 30,000 cubic meters of a pasty-white man-made mix of snow and ice that’s called, cutely, “snice,” to build the hotel each year. In a few months, everything from the king-size bedframes to the benches in the bar would be reduced to puddles—or, more precisely–reabsorbed into the river.

THE BIG FREEZE

Building the ice hotel isn’t so much an annual process as a never-ending one. But if you had to specify a starting point for the endeavor it would be sometime in November, when the river freezes over. That’s when the production team, led by production manager Alf Kero, sections out a 14,000 square foot swath of ice with red plastic rods typically used to mark snow-covered roads. All winter long, Kero and his team will cultivate and monitor this patch—which will eventually become the raw material for the next year’s hotel.

An average of two meters of snow blankets the village over the winter, but workers plow this special patch of river with a front-end loader to keep it clear of precipitation. This ensures that the ice grows downward, into the still waters of the river below, rather than hardening upward. The result is ice that is crystal-clear, free from bubbles and cracks, and it’s this naturally formed glass-like ice that the hotel has made its trademark.

In December, during the weeks that the sun doesn’t come above the horizon, the entire river, which reaches depths of more than 60 feet, is frozen solid. Because of all that ice, the temperature in Jukkasjärvi can be 10 to 20 degrees colder than the nearby mining city of Kiruna, just 11 miles to the east. But by February, as the days are beginning to lengthen, the river is slowly beginning to thaw from its bed up. This is when the team begins to gear up to harvest the ice for the next year’s hotel, carefully monitoring its thickness. When it’s around three feet thick, usually in early March, it’s time for the harvest to begin.

BUILDING BLOCKS

The ice patch is gridded out into squares that measure roughly 20 square feet, and then the team slices the ice using a vertical saw mounted on a front-end loader, specially designed for the task by the team with the help of a local construction firm. Each cube, weighing nearly two tons, is lifted out of the river with a forklift. “The river flow is quite gentle in the area where we pick up the ice blocks,” Kero tells me, “but the ice can be slippery and at times it can be very windy so it is important to wear suitable safety equipment and ensure that the staff is trained and working in teams, never alone.” Altogether, the team harvests 5000 tons of ice this way.

Once a block is out of the river, the crusty top layer is sawed off, and then the blocks are sorted by clarity. The clearest of them are designated for use in the hotel rooms and to manufacture glasses—for the hotel's bar and three more Ice Bars the IceHotel runs, in Stockholm, Oslo, and London. During the summer, while the temperature outside reaches the 60s and the sun stays up all night, the giant blocks sit in two giant sub-freezing warehouses.

You can still visit the IceHotel in the summer—right now, the production team is busy building an IceBar and sample rooms that are open inside the hotel’s hangar-like art center each year. Once that’s done and the ice harvest has been completed, the team turns its attention to the planning of next fall’s hotel. “The first steps are a number of creative brainstorming meetings, where we set out the plans for the architecture and art,” says Sofi Routsalainen, a member of the Art and Design group, which oversees the production of the hotel. Over the summer, they’ll carefully choose the 40 artists who will create next year’s art suites from 200 applicants.

WINTER IS COMING

As winter begins to descend, it’s time to get ready to start construction on the new hotel. It takes a team of about 100 people—including builders, artists, lighting engineers, snice casters, tractor drivers, and the art and design group—to build the structure. In October, as the river begins to freeze, the production team prepares the grounds and wall moulds and makes sure electricity and sewage are in order, while they wait for the temperature to drop. A support wall is erected out of steel vaults.

When the ground freezes and there’s been a week of temperatures below 19 degrees Fahrenheit, it’s time to start spreading snice for the hotel floor. Snice acts like a paste and looks like the crust that builds up in a malfunctioning freezer. It’s made by pumping water from the river and blowing it through “snow cannons,” which results in tiny ice particles mixed with air. The substance is structurally stronger and more resistant to the sun than sheer ice, and has the insulating qualities of snow. A hotel built of pure ice would be much colder inside, and would melt quicker in the spring.

To construct each corridor of the hotel, a row of arch-shaped steel vaults are erected, and then sprayed with snice and left to set for a few days. Once they’ve frozen, the vaults are lowered onto skis and pulled out with a tractor. Internal walls are built using the same process. Once the corridor is divided into a number of rooms, doors are cut using a chain saw, and the LED lights are installed. (There’s no plumbing—if hotel guests have to use the bathroom in the middle of the night, they must venture to an attached warm building. Ask me about this some other time!) When the rooms are completed, the team stocks some of them with extra ice blocks—these will become the art suites.

For more than two weeks each November, the visiting artists chosen to create the year’s art suites work in the freezing rooms, using chisels and chain saws to carve the rooms they have planned. Then in early December, once the reception area, bar, and at least one wing of rooms are ready, the hotel officially opens for business. From then until the structure becomes unsafe to occupy in April, visitors will fill their days with ice sculpting lessons and snowmobile sojourns. They might even attend one of the 150 weddings celebrated each year in the ice chapel. As for the nights: those are spent out on the frozen Torne, watching for the Aurora Borealis—and learning the value of a good down sleeping bag.