Ray Cantrell was practically suffocating. Hiding in a freezer in the lobby of the RKO Golden Gate Theater in San Francisco late in April 1971, Cantrell had spent hours peering through a small vent in the appliance, scanning the crowd for anyone who resembled the widely circulated police sketch of the most notorious criminal-at-large in the country: the Zodiac Killer.

It was all part of an ambitious plot hatched by Cantrell's friend, a fast food franchisee named Tom Hanson. Hanson had arranged for Cantrell and several other co-conspirators to station themselves in various places around the cinema during the week-long engagement of Hanson’s low-budget film, the aptly titled The Zodiac Killer.

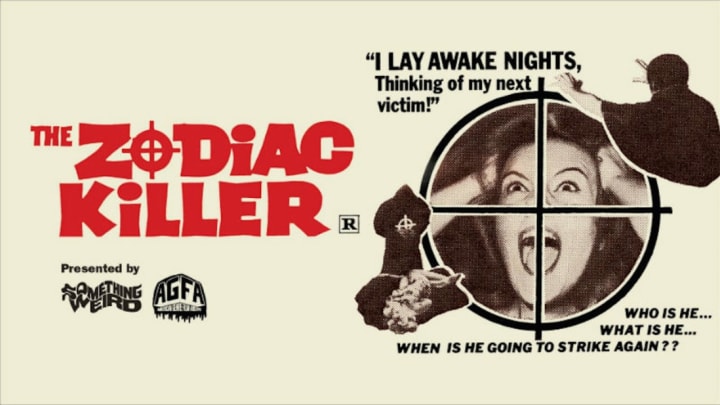

Dramatizing the recent murders and subsequent taunting by the killer via letters to newspapers, the movie was made for just $13,000 in a matter of weeks. Its quality was irrelevant: Hanson’s real intention in making the film was to see if he could tempt the Zodiac Killer himself to the film's premiere, where he had set an elaborate trap to single him out from the audience. If it worked, Hanson would be hailed as a hero. If it didn't, he’d be virtually broke.

Early on, it looked as though things would go south. Cantrell had limited air in the freezer, and was dragged out just in time on one occasion (a minute or two more and he likely would have lost consciousness). But before the week was out, Hanson believes he came to face to face with the Zodiac. At the urinal.

“You know,” the stranger said, unzipping his fly, “real blood doesn’t come out like that.”

Initially, Hanson didn't have designs on becoming the next Martin Scorsese. After relocating to Los Angeles from Minnesota in the 1960s, Hanson had found his niche as the owner of several Pizza Man franchises and a handful of Kentucky Fried Chicken locations.

“Then my underwriter went broke," Hanson, now 81, tells Mental Floss. "He was supposed to bring us public. I thought, 'Well, if I’m going to go down, I’m going to do what I really want to do, which was make films.'" Hanson had acted or worked on a half-dozen small film projects since arriving in California, developing contacts and friendships with a number of performers and crew members. He knew the world of low-budget filmmaking meant working quickly and cheaply, with only a small chance of breaking out.

At the same time Hanson decided to mount a production, San Francisco was unraveling. On December 20, 1968, a teenaged couple had been found shot to death in the young man's car near Vallejo, California. On July 4, 1969, another young couple was shot in a car; 22-year-old Darlene Ferrin was killed while her friend, 19-year-old Mike Mageau, was seriously wounded. Weeks later, three major San Francisco newspapers received a handwritten letter claiming credit for the crimes and revealing details only the killer would know. Signing the correspondence with a circle and cross, the author would later introduce himself: “This is the Zodiac speaking.” He killed two more people before the year was up.

As 1970 passed with no breaks in the case, Hanson had an audacious thought. “What if I do a movie and set a trap to catch him? I thought he’d go see a movie about himself. He’d have to.” (In another letter, the obviously publicity-hungry killer even mused about who should play him in a movie.)

Shot in just a few weeks in early 1971 and edited just as quickly, The Zodiac Killer (originally titled Zodiac) represents no new ground in the exploitation film genre. Hanson hired a friend, Hal Reed, to play the killer, whom he imagined to be a postman by day and a murderous psycho by night; Paul Avery, the increasingly paranoid journalist who thought he might be targeted by the killer, met with Hanson a few times to discuss details of the case. “He’d wait in the alley near the restaurant and wait for me to come in,” Hanson says. “He was really jumpy.”

Hanson spent $13,000 on The Zodiac Killer, exhausting most of his savings. He booked a week-long premiere engagement at the RKO Theater in San Francisco and bought ads in local newspapers. Without telling authorities of his plan (“They might have tried to stop it,” Hanson says), the filmmaker enlisted six friends, including Reed, to monitor the crowd during the screenings.

The plan worked like this: Each theatergoer would get a sweepstakes entry card they would be instructed to fill out. The prize was a Kawasaki motorcycle that stood on a podium in the lobby. By dropping the card through a slot, attendees were inadvertently giving Hanson a handwriting sample he could compare to the letters published in the papers.

“We all had positions we traded out,” Hanson says. One would actually be inside the podium where the cards were being dropped, evaluating handwriting on the fly. If he saw one that resembled the writing in the published letters, he could flip a switch activating a light that another team member hiding in the freezer would see. Other men were stationed outside, in the projectionist’s room, and in the lobby. With a match, Hanson would attempt to corral and hustle the suspect into an office to detain him.

While a fine idea in theory, the stakeout proved tedious. During one freezer stint, Cantrell—who also co-wrote the film—nearly passed out. During the confusion, someone had dropped a card declaring “I am the Zodiac, I was here,” but no one was inside the podium to evaluate it in real time.

On the last night of the engagement, Hanson interrupted his surveillance for a bathroom break. “I was standing at the urinal and thought I heard the door open,” he says. “I turned around but didn’t see anyone.”

Without a sound, a man had materialized at the urinal next to Hanson’s, remarking about a graphic scene in the movie and how “real blood” wouldn’t come out of a body like that. “I zipped up, turned, and saw the same face that was on the wanted poster. Same eyes, nose, mouth, hair, everything. I thought, 'Son of a bitch, it’s him.'"

Hanson stresses that, as the proprietor of several chain restaurants, he had been held up a number of times by robbers and quickly learned to study faces for later identification. Confronting the man in the lobby, Hanson led him to a nearby office and had his friends surround him. "I looked right into his eyes and told him Paul Stine was my brother." (Stine was a cab driver who was shot and killed by the Zodiac in October 1969, and the lie was designed to break the suspect's composure.) "But he didn’t blink."

In fact, the man seemed to be making friends with Hanson’s crew, bonding over shared experiences in the military. With no legal authority to hold his suspect, Hanson watched as he ambled off. But it wouldn't be the last time he looked into the face of the man he believed might be one of the most notorious killers of the 20th century.

The Zodiac Killer finished its engagement at the RKO and ended up getting booked in a few other theaters, but it was far from a hit. Hanson made another film in 1972, a drug comedy titled A Ton of Grass Goes to Pot, before retreating to Wisconsin to try and recalibrate his business ventures. When he returned to California in 1974, he decided the man he saw at the RKO needed to be monitored.

"I needed to get back on my feet and look further into this guy," Hanson says.

With the aid of private detectives, Hanson cooked up a new plot. Having obtained his address from their investigation—the man originally gave a hotel address at the premiere—Hanson sent a postcard informing his suspect that he had won a prize. When he dispatched the detectives to deliver the prize box, they were supposed to announce they had made a mistake and take it back—that way, Hanson would have his fingerprints on the package. But no prints were found.

“Another time, the detective phoned where he was working at the time, which was Bank of America,” Hanson says. “They asked for his personnel file and when the bank asked why, they said, ‘Well, we think he’s the Zodiac.'" The man was soon fired.

Eventually, Hanson gave up the chase. The killer hadn’t struck since 1969 and hadn’t written a letter since 1974—and investigators did not believe the handwriting samples Hanson had collected were a match.

But the lure of identifying Zodiac has never completely left. Today, both Hanson and his grandson continue to research the man he first spotted in the RKO bathroom, attempting to excavate any information that might connect him to the murders. Though The Zodiac Killer largely disappeared from public view following its original limited release, it was recently unearthed by the American Genre Film Archive and released on Blu-ray in July. A forthcoming book and documentary, Zodiac Man, may provide the suspect's name, which has yet to be publicly disclosed. All Hanson will say is that the man is still alive.

If Hanson is correct, it'll end a search that has continued for nearly a half-century, proving he’ll go to any lengths to corner his elusive prey.

Well, almost any lengths.

"I never got in the freezer," Hanson admits.