In 1850, a young naval captain named Frederick E. Forbes arrived in the African kingdom of Dahomey (today’s Benin) to see the powerful monarch King Ghezo on an antislavery mission from the British Empire. As was standard for meetings of dignitaries, gifts were exchanged. Among those given to Forbes—as a formal offering to Queen Victoria—was a 7-year-old girl.

Two years earlier, the girl’s life had been upended. Her village of Okeadan (in modern-day Nigeria) was raided, her family was killed, and she was captured as an enslaved person. Many sources suggest that the girl was the daughter of a chief or of royal lineage, but Forbes wrote that of "her own history she has only a confused idea"; he speculated that she was "of a good family" because she had been kept alive at court and not sold. With Forbes's arrival in the court of King Ghezo, her fortunes—as dramatized in the PBS series —unexpectedly changed.

Forbes was part of the Royal Navy's antislavery squadron that patrolled and captured ships full of enslaved people off West Africa. Though Great Britain had been a prominent force in the transatlantic trade of enslaved people, by 1838, under Queen Victoria, parliament had abolished slavery throughout the empire.

It may seem ironic that a man opposed to slavery would accept a human as a gift, which Walter Dean Myers, in his young reader book At Her Majesty's Request: An African Princess in Victorian England, calls “a present from the King of the blacks to the Queen of the whites.” But as Forbes wrote in his journals, to refuse her would be to sign "her death-warrant.” He believed that, "in consideration of the nature of the service I had performed, the government would consider her as the property of the Crown," so the government would take responsibility for her care. And, he was immediately impressed by her brightness and charm, calling her "a perfect genius.” He renamed and baptized the young girl after himself and his ship, the HMS Bonetta. From that moment forward, she was known as Sarah Forbes Bonetta.

Queen Victoria got word of Sarah's rescue, and on November 9, 1850, Forbes presented Sarah to the Queen at Windsor Castle. Both Forbes and the Queen likely saw a purpose for her in England’s promotion of Christianity in Africa. "God grant she may be taught to consider that her duty leads her to rescue those who have not had the advantages of education from the mysterious ways of their ancestors,” Forbes wrote hopefully.

In her essay in Black Victorians/Black Victoriana, Joan Anim-Addo suggests that Queen Victoria’s decision to pay for Sarah's education and guide her upbringing "took into careful consideration Forbes's projection of a future for Sally in missionary circles, particularly in relation to Sierra Leone.” In the 1800s, the Sierra Leone Colony was part of the British Empire, and administered by Anglican missionaries with the purpose of creating a home for freed, formerly enslaved people.

Sarah stayed for a time with Forbes's family and visited the Queen regularly. In her diary, Queen Victoria wrote fondly of Sarah, who she sometimes called Sally. “After luncheon Sally Bonita, the little African girl came with Mrs Phipps, & showed me some of her work. This is the 4th time I have seen the poor child, who is really an intelligent little thing.”

The captain died in 1851, and Sarah, then about 8 years old, was sent to a missionary school in Freetown, Sierra Leone in May of that year. The school forbade students from wearing African dress and speaking their native languages, and promoted English culture as a path to civilization. Sarah was a model student, but in 1855, she returned to England. According to Queen Victoria: A Biographical Companion, Sarah was unhappy at the school, and the Queen agreed to her departure.

Her royal sponsor placed her with a new family, the Schoens, longtime missionaries in Africa who now lived at Palm Cottage in Gillingham, Kent, about 35 miles east of London. Sarah seemed to get along well with her new guardians—in her letters she addressed Mrs. Schoen as “Mama.” One of her letters, reprinted in Myers’s At Her Majesty’s Request, was sent from Windsor Castle and hints at the Queen’s care for her well-being: "Was it not kind of the Queen—she sent to know if I had arrived last night as she wishes to see me in the morning.”

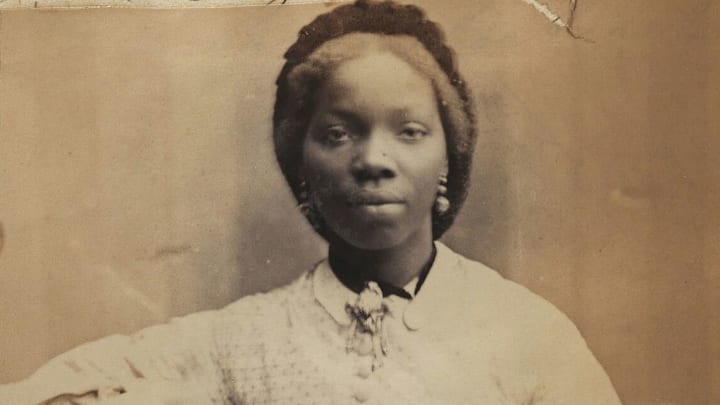

The Schoens’ daughter Annie later remembered how Sarah "was very bright and clever, fond of study, and had a great talent for music, and soon became as accomplished as any English girl of her age.” Furthermore, Queen Victoria "gave constant proofs of her kindly interest in her," including invitations to Windsor at holidays, and gifts like an engraved gold bracelet. In an 1856 photograph, taken when she was around 13, Sarah is posed like an English lady, a sewing basket at her elbow, and a bracelet, perhaps the one from the Queen, on her wrist.

Despite living with the English elite, and receiving a lady’s education, Sarah had little control over her destiny. And like most women of the 19th century, she was expected to marry when she reached the proper age. For Sarah, that age was 19. A suitor was found: Captain James Pinson Labulo Davies, a Sierra Leone-born British naval officer. His own parents, of Yoruba descent, had been freed from slave ships by the Royal Navy, and Davies had attended the same missionary school as Sarah. After retiring from the navy, he became a successful merchant vessel captain and businessman. They seemed to have a lot in common, but Sarah did not love him. "I know that the generality of people would say he is rich & your marrying him would at once make you independent," Sarah wrote to Mrs. Schoen, "and I say, 'Am I to barter my peace of mind for money?' No—never!”

Yet she could not disobey the Queen, and in August 1862, in St. Nicolas Church in Brighton, she married Davies. In a series of 1862 carte de visite photographs now at the National Portrait Gallery in London, Sarah poses in her voluminous white wedding dress with her new husband. Her lively eyes stare directly at the viewer in one shot, with a gaze that seems almost defiant.

The couple moved to Sierra Leone, and then to Lagos. With royal permission, they named their daughter, born in 1863, after Queen Victoria, who became her godmother. The Queen presented baby Victoria with a gold cup, salver, knife, fork, and spoon engraved with an affectionate message: "To Victoria Davies, from her godmother, Victoria, Queen of Great Britain and Ireland, 1863.”

Sarah and James had two more children, but Sarah’s health began to wane. She went to Madeira, a Portuguese island, to seek a cure for tuberculosis. Sadly, she died in 1880 at just 37 years old.

Upon hearing that news, Queen Victoria wrote in her diary that she would give her goddaughter Victoria Matilda Davies an annuity of £40 (which has the economic power of £63,000 today).

Many mysteries remain about Sarah Forbes Bonetta’s life. In her letters, she wrote only of current events. She never reflected on her childhood, the loss of her family, or her dramatic rescue. She also never mentioned royal blood, though the popular notion of Sarah as an “African princess” endures.

Queen Victoria’s care for Sarah may have been partly a moral mission, fueled by the desire to spread Christian righteousness in the British colonies. Yet in an era when slavery was still practiced in the United States, her support and care for Sarah and her family was a powerful statement of tolerance.