“What the hell was that?” For a moment, members of the production staff monitoring the stage at California's Pasadena Civic Auditorium forgot about the control panels in front of them and exchanged puzzled looks with one another. As the team charged with overseeing the ABC special Motown 25: Yesterday, Today, Forever, a celebration of the famed record label’s silver anniversary, they were typically too focused on their jobs to become starstruck. But what they were witnessing was something else entirely.

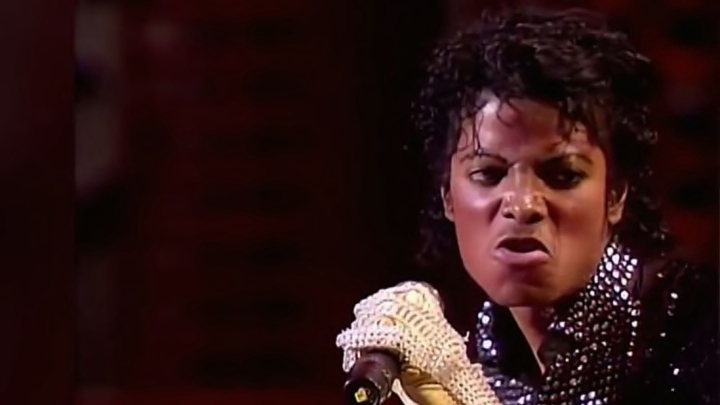

Onetime Jackson 5 bandmate Michael Jackson had taken the stage solo to perform “Billie Jean,” which was already the number one song on the Billboard Top 100 chart. In between all the twisting, contorting, and spinning, Jackson took a fleeting moment to glide backwards on his feet. It had the smooth kinetic energy of someone skating on ice. It lasted barely a second. The crowd erupted.

Jackson had not used the dance move in rehearsals for the show. It was a surprise to everyone, including the live audience and the 33.9 million people who would watch the tape-delayed event on television on May 16, 1983. Jackson was already a superstar, but his moonwalk would take him to another stratosphere of fame. And although many assumed Jackson invented the gliding step himself, he was simply following in the footsteps of dance giants from the past.

Usually referred to as the back slide or the back float, the seemingly weightless backward slide had touched down across a number of decades and performers before Jackson's interpretation debuted on March 25, 1983. Famed French mime Marcel Marceau performed an act he titled “Walking in the Wind,” in which he seemed to be bracing against imaginary gale forces, his feet trying to find purchase on the ground. Jazz singer Cab Calloway pulled it off in performances; so did tap dancer Bill Bailey (as seen above) in the 1950s. James Brown incorporated the move into his stage shows, as did Bill “Mr. Bojangles” Robinson. David Bowie performed a more economical version of it during the 1973 tour for his Aladdin Sane album.

While Jackson credited Brown and Marcel as being particular influences on his performance style, he first learned of what he came to call the "moonwalk" after seeing two break-dancers appear on a 1979 episode of Soul Train. During the show, Geron "Caszper" Canidate and Cooley Jaxson performed a routine set to Jackson’s “Workin’ Day and Night.” The singer remembered the performance and asked his staff to arrange a meeting between him and both men in Los Angeles while he was preparing for the Motown special in early 1983. Jackson asked them to teach him the back slide, which he practiced until he was satisfied he had it down. (Cooley would later express disappointment that Jackson never credited the duo directly. The singer wrote in his autobiography, Moonwalker, that the move was a “break-dance” step created on street corners. While that could be true, it was Cooley and Jaxson who gave Jackson a tutorial.)

Although it may look like an optical illusion, the step is the result of weight-shifting. Dancers begin on their right foot, heel raised, and weight bearing on the right. As they lower the right heel, the left foot moves backward until the toes are aligned with the heel of the right. The left heel is then raised, weight is shifted to the left, and the process repeats itself. For those who are not particularly agile, it can look clumsy. For Jackson, who had been dancing practically his entire life, it was seamless.

For the Motown special, Jackson reportedly agreed to appear with his brothers, the Jackson 5, only if Motown owner and show producer Berry Gordy allowed him a solo performance. Jackson’s Thriller album had been released in November 1982 and was on its way to becoming one of the most successful releases of all time. It’s likely Jackson didn’t feel like he needed the appearance, and some accounts relate that Jackson was initially reluctant to do it because he feared being overexposed. Gordy’s producer, Suzanne de Passe, convinced him the show wouldn’t be the same without the Jackson 5.

Whatever got Jackson on stage that evening, he was clearly prepared for the moment. Short pants and white socks drew attention to his feet; he insisted a stage manager rehearse the placement of his hat following the Jackson 5 performance so that it would be within reach when he segued into his solo performance.

“I have to say, those were the good old days,” Jackson told the crowd after finishing with his brothers. “Those were good songs. I like those songs a lot … but, especially, I like the new songs.” It may have sounded off the cuff, but Jackson’s mid-performance speech was actually written by Motown 25 scriptwriter Buz Kohan.

With that, Jackson got down to business. “Billie Jean” was the only non-Motown song performed during the special, and it felt like a jolt of energy in a sea of nostalgia. Jackson, who was 24 years old at the time, moved effortlessly. Tossing his hat to the side and mouthing lyrics into the microphone, the contrast between Jackson in the middle of a medley with his brothers and then alone on stage was striking. Though he was two solo albums deep by this point, the performance helped cement that he was out on his own.

Jackson spent nearly three and a half minutes singing before debuting the moonwalk. It lasted barely a second but seemed to send the crowd into a mania. With 20 seconds to go, he took another few brief steps backward. After the song played out, Jackson received a standing ovation.

When the performance aired several weeks later on ABC, Motown 25 was a ratings hit. Jackson’s reputation as a live entertainer benefited from a broadcast network audience, and the moonwalk became linked to his routine. Fred Astaire called to congratulate him, a gesture that Jackson—a huge Astaire fan—could never quite believe.

Jackson’s fame led to an untold number of people trying to perfect the moonwalk, with varying degrees of success. Anyone who thought it included some camera or visual trickery may have been dismayed to find it simply required some lower-limb dexterity. Those who got the hang of it were able to impress friends. Those who didn't probably felt a little disappointed at their lack of coordination, especially when they heard that Jackson’s pet chimpanzee, Bubbles, learned to do a variation of it.