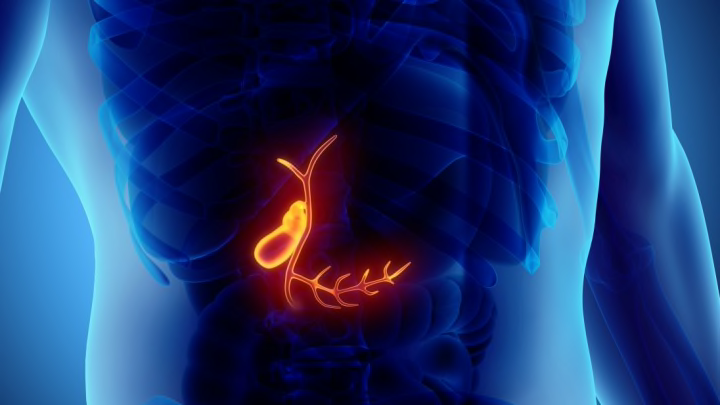

Don't feel too bad if you forgot you have a gallbladder—it's one of those body parts that people tend to ignore unless there's a problem. Here's a refresher: It's that small pouch beneath the liver whose primary function is to store bile, which helps you digest fats. So the next time you wolf down a Quarter Pounder with cheese, you can thank your gallbladder for doing its part. Here are a few other things you should know.

1. IT’S THE SIZE OF A SMALL PEAR, AND IT LOOKS LIKE ONE, TOO.

Right before you take your first bite of pizza, your gallbladder is full of bile—an alkaline fluid that's produced in the liver, transported to the gallbladder, and then released into the small intestine to help break down fat and bilirubin, a product of dead red blood cells. The organ can hold the equivalent of a shot glass of the yellow-green liquid, which causes it to swell up to the size of a small pear.

When you eat certain foods—especially fatty ones—the gallbladder releases the bile and deflates like a balloon. Although most gallbladders are roughly 1 inch wide and 3 inches long, there are notable exceptions. In 2017, a gallbladder removed from a woman in India measured nearly a foot long, making it the longest gallbladder in the world.

2. YOU CAN LIVE WITHOUT IT.

You don’t need your gallbladder to live a full and healthy life. Just ask British playwright Mark Ravenhill, who wrote an account for the BBC about getting his gallbladder removed after a gallstone—a solid object made of cholesterol or calcium salts and bilirubin—had moved painfully into his pancreas. "'The gallbladder's completely useless,'" Ravenhill recalled his doctor explaining. "'If it's going to be a problem, best just to take it out.'"

In addition to preventing more gallstones from forming, a physician may recommend that a patient’s gallbladder be removed due to other diseases, like cholecystitis (inflammation of the gallbladder) and cancer. In most cases, removing it doesn’t affect digestion, but there can be some complications. "People can certainly live without one, but they do have to watch their fat intake," says Ed Zuchelkowski, an anatomist and biology professor at California University of Pennsylvania. People who don't have gallbladders still produce bile, but it flows directly from the liver to the small intestine. The only difference is that "you would not have as much bile readily available to release," Zuchelkowski tells Mental Floss, which could cause minor problems like diarrhea if you're eating fatty foods.

3. OUR HUNTER-GATHERER ANCESTORS MAY HAVE NEEDED IT MORE THAN WE DO.

"[The gallbladder] probably was more important to people in days when they would eat fewer meals and larger meals," Zuchelkowski says. This was generally the situation that our hunter-gatherer ancestors found themselves in. As Ravenhill notes, "feast or famine was the general rule." Nomadic groups ate large slabs of meat about once a week, and the gallbladder helped to quickly digest the onslaught of protein and fat.

Even though our diets and eating habits have changed drastically since then, evolution hasn't caught up—we still have the same digestive system. It's probably for this reason that "most meat-eating animals have a gallbladder," Zuchelkowski says. "Dogs do, cats do—they can concentrate bile just like we do, but I think you’d find that in animals that only eat vegetation, that’s where it’s likely to be missing.” However, Zuchelkowski notes that the gallbladder also helps you absorb fat-soluble vitamins like A, D, E, and K, so it still serves a useful function in people who are vegetarians.

4. ASTRONAUTS ARE ENCOURAGED TO GET THEIRS REMOVED.

A 2012 report from the Canadian Journal of Surgery recommended that astronauts consider having their appendix and gallbladder removed—even if their organs are perfectly healthy—to prevent appendicitis, gallstones, or cholecystitis from setting in when they’re far, far away from Earth's hospitals. “The ease and safety of surgical prophylaxis currently appears to outweigh the logistics of treating either acute appendicitis or cholecystitis during extended-duration space flight,” the authors wrote.

5. ALEXANDER THE GREAT LIKELY DIED FROM A GALLBLADDER GONE BAD.

Alexander may have been great at conquering entire empires, but his organs weren’t exactly up to the task. The king of Macedonia died at the age of 34, and some historians believe that the cause was peritonitis (inflammation of the peritoneum, the tissue lining the abdomen), which itself was a result of acute cholecystitis. “Historians have suggested that the fatal biliary tract disease was fueled by excess consumption of alcohol and overeating at a banquet that Alexander threw for his leading officers in Babylon,” author Leah Hechtman writes in Clinical Naturopathic Medicine.

6. THE DOCTOR WHO CONDUCTED THE FIRST SUCCESSFUL GALLSTONE REMOVAL SURGERY DIDN'T KNOW WHAT HE WAS LOOKING FOR.

Gallbladder-related ailments have been afflicting humans for thousands of years, as evidenced by gallstones found in Egyptian mummies. And for thousands of years, people put up with it because they didn’t know what was wrong or how to fix it. In fact, it wasn’t until 1867 that the first cholecystotomy (removal of gallstones) was carried out. The surgery was performed by Dr. John S. Bobbs of Indianapolis, who had no idea what ailed his patient, 31-year-old Mary Wiggins, until he cut open a sac that he later realized was her gallbladder and “several solid bodies about the size of ordinary rifle bullets” fell out, according to The Indianapolis Star. Amazingly, Wiggins survived and lived to the age of 77. Fifteen years after this surgery, the first cholecystectomy (removal of the gallbladder) was performed in Germany.

7. THE WORLD RECORD FOR MOST GALLSTONES EVER REMOVED FROM A PERSON'S BODY STANDS AT MORE THAN 23,000.

Unlike the Guinness World Record for most Twinkies devoured in one sitting, this isn’t the kind of record you’d enjoy setting. In 1987, an 85-year-old woman complaining of severe abdominal pain showed up at Worthing Hospital in West Sussex, England, and doctors found a shockingly high number of gallstones—23,530, to be exact. In May 2018, a similar (albeit less severe) case of gallstones was reported in India, where a 43-year-old man underwent surgery to have thousands of them removed. “Usually we get to see two to 20 stones, but here there were so many and when we counted them, it was a whopping 4100,” the surgeon told Fox News.

8. SOME EASTERN CULTURES BELIEVE THERE’S A LINK BETWEEN THE GALLBLADDER AND HEADACHES.

Some practitioners of Eastern medicine—especially Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)—purport that gallbladder problems can cause certain kinds of headaches. TCM practitioners say our internal organs are connected to channels called meridians, which direct several fundamental substances—like blood, other bodily fluids, and qi (vital life energy)—throughout the body. The gallbladder meridian, for instance, runs along the side of the head near the temple. Through the practice of acupuncture, tiny needles are inserted into the skin along the gallbladder meridian in an effort to relieve tension and free up blocked qi. (Western scientists tend to disagree on what, if any, benefit acupuncture offers.)

9. IN CHINA, BOLD PEOPLE ARE SAID TO HAVE A “BIG GALLBLADDER.”

Speaking of China, the country's primary language, Mandarin, hints at a link between organ function and personality. For instance, a word that’s assigned to bold and daring people translates to “big gallbladder,” and brave people are said to have “gallbladder strength,” according to The Conceptual Structure of Emotional Experience in Chinese. The word for coward, on the other hand, translates to “gallbladder small like mouse.” (Interestingly, mice do in fact have gallbladders, but rats don’t.)

10. WESTERN PHILOSOPHERS ALSO THOUGHT ONE'S TEMPERAMENT HAD TO DO WITH THE GALLBLADDER.

You may remember learning something about the four humors during a high school lesson on ancient Greece. The theory, originating with Hippocrates, held that a person’s temperament was influenced by one of four bodily fluids: black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood. Yellow bile, stored in the gallbladder, was said to make people choleric, or irritable. Disease was blamed on an imbalance of these four humors, and this remained a popular theory up until the 18th century. Because of this theory's longstanding influence, the word gall—a synonym for bile—also meant “embittered spirit” during medieval times. It wasn’t until 1882 that the word took on the meaning of "impudence" or "boldness" in American English—as in “I can’t believe he had the gall to finish that Netflix series without me.”

11. ANCIENT ETRUSCANS USED THEM FOR DIVINATION.

Well, not human gallbladders. Ancient Etruscans, a group of people who once lived in present-day Tuscany and whose civilization became part of the Roman empire, practiced a type of divination called haruspicy. The soothsayers were called haruspices (literally “gut gazers”), and they looked for clues from the gods in the markings, coloring, and shape of a sacrificial sheep’s liver and gallbladder. This was often done before the Romans went into battle, but the practice was never adopted as part of the state religion.

12. SOME GALLBLADDERS SPORT A PHRYGIAN CAP.

A crease called a "Phrygian cap" at the base of the gallbladder occurs in about 4 percent of people. Its odd name is something of a misnomer. It comes from its resemblance to a type of peaked felt hat called a pileus, worn by emancipated slaves in ancient Rome; the design was similar to the peaked caps then worn in Phrygia, a region in modern-day Turkey. Much later, during the French Revolution, people took to wearing Phrygian caps—which they likely confused with the pileus's style—as symbols of their freedom from tyranny. In the 20th century, the Smurfs started wearing them.

As for the aforementioned gallbladder abnormality, there’s no deeper symbolism in its name. The way it folds over just looks a lot like a Phrygian cap. Despite being a “congenital anomaly,” as a 2013 study published in Case Reports in Gastroenterology puts it, the condition typically causes no symptoms or complications.