The First World War was an unprecedented catastrophe that killed millions and set the continent of Europe on the path to further calamity two decades later. But it didn’t come out of nowhere. With the centennial of the outbreak of hostilities coming up in August, Erik Sass will be looking back at the lead-up to the war, when seemingly minor moments of friction accumulated until the situation was ready to explode. He'll be covering those events 100 years after they occurred. This is the 103rd installment in the series.

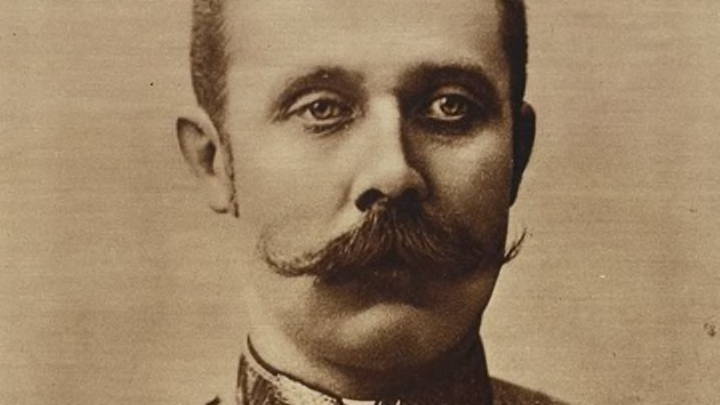

February 17, 1914: The Archduke Seals His Own Doom

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914 gave Austria-Hungary the excuse it needed to attack Serbia, inadvertently triggering the First World War. But the Archduke’s presence in Sarajevo that day was purely a matter of chance—or more precisely, petty political maneuvering.

Emperor Franz Josef had appointed his cantankerous nephew inspector general of the Austro-Hungarian army in August 1913, in order to acquaint the heir to the throne with the empire’s military affairs. Now armed with sweeping (if rather vague) authority, Franz Ferdinand was eager to assert control over the Dual Monarchy’s armed forces—especially if it allowed him to pull rank on the chief of the general staff, Conrad von Hötzendorf, a former friend who’d fallen out of favor due to his persistent advocacy of war against Serbia.

Conrad found it especially annoying when Franz Ferdinand showed up to observe the army’s annual maneuvers, so naturally the Archduke always made sure to be there. In 1914 the maneuvers were set to take place in Bosnia, with the clear goal of intimidating neighboring Serbia, and Franz Ferdinand—who opposed war with the troublesome Slavic kingdom, but understood the need for occasional saber-rattling—let it be known he planned to attend. But his itinerary didn’t include the provincial capital of Sarajevo, a third-tier town of 50,000 with little to recommend it to a globetrotting aristocrat.

Sarajevo was only added to the Archduke’s itinerary at the insistence of the provincial governor, Oskar Potiorek, an ambitious functionary determined to show Vienna how his enlightened administration had won over Bosnia’s restive Slavs. Of course this was pure fantasy—Potiorek had declared a state of emergency in May 1913 and never rescinded it—and Franz Ferdinand, knowing the risks, was understandably reluctant. But Potiorek had another card to play. If the Archduke paid an official visit to Sarajevo, his “morganatic” wife Sophie would be accorded the ceremonial recognition usually denied her in Vienna (as a minor aristocrat she was considered inferior and coldly ignored at court). After years of snubs, Franz Ferdinand was probably eager to show Sophie off with the pomp and circumstance he felt she deserved.

Whatever his reasons, on February 17, 1914, the Archduke finally gave in to Potiorek’s nagging and agreed to visit Sarajevo the day after the maneuvers, scheduled for June 26 and 27. They couldn’t have chosen a worse date: June 28, St. Vitus’ feast day (Vidovdan in Serbian) is the anniversary of the traumatic Serbian defeat at the Battle of the Field of Blackbirds (Kosovo Polje), where the Ottoman Turks wiped out the badly outnumbered Serbs in 1389. A key event in the formation of Serbian national identity, the Battle of Kosovo Polje symbolizes Serbia’s long struggle against foreign oppression, and has traditionally been commemorated with church rituals, the recitation of epic poetry, and patriotic gatherings.

Even worse for Franz Ferdinand, the semi-legendary history of Kosovo Polje included the story of Miloš Obilić, a brave Serbian knight who avenged the defeat by assassinating the Ottoman Sultan Murad on the field of battle, martyring himself in the process. The symbolic link between the medieval Turkish despot and the modern Austrian Archduke was all too obvious to Bosnian Serb nationalists, especially in light of rumors that the Austro-Hungarian army maneuvers were actually a cover for a surprise attack on Serbia.

Meanwhile, the head of Serbian military intelligence, Dragutin Dimitrijević, codename Apis, was busy plotting the assassination of some high-ranking Austrian official. In December 1913 or January 1914 several members of Dimitrijević’s ultranationalist terrorist organization, Unity or Death (also known as the Black Hand) met in Toulouse, France, to plan the murder of Potiorek, but this conspiracy soon fizzled out. Afterwards one conspirator, Muhamed Mehmedbašić, returned to Sarajevo and got in touch with his friend and fellow Black Hand member Danilo Ilić, who eventually put him in touch with several other would-be assassins, including a young Bosnian Serb named Gavrilo Princip. In March 1914 they learned of the Archduke’s coming visit to Sarajevo, and a new plot began to form.

See the previous installment or all entries.